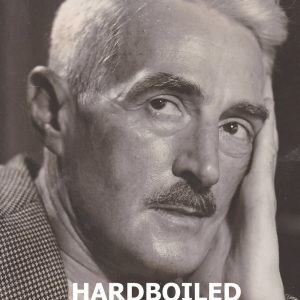

Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and the Continental Op could combine forces and still be hard-pressed to blow Ken Fuller’s cover. Praxis Press, publisher of Fuller’s Hardboiled Activist: The Work and Politics of Dashiell Hammett, provides the reader with the obligatory biographical information of the author, comprised of a list of book titles and this sentence: “A former trade union official from London, Ken Fuller has lived in the Philippines since 2003.” On Amazon, Fuller’s author’s page offers nothing except the message that there is “no image available.” By the time he became the object of Fuller’s scrutiny, Dashiell Hammett had already commanded the attention of no fewer than seven biographers. Playwright Lillian Hellman, Hammett’s long-time companion and sometimes co-writer, had been surveyed even more frequently, and thus Hammett along with her.

One might ask, then, what prompts a British former trade-union official to offer the world yet another biography of Hammett. Interestingly, Fuller references Monthly Review co-founder Leo Huberman twice in the book, suggesting that part of his goal is to elucidate Hammett’s Marxism. In so doing, he sets himself apart from most of the writer’s previous biographers.

Hammett abruptly and inexplicably stopped writing prose in the mid–1930s, shortly before turning forty. According to Fuller, it would be several years before he arrived at Marxism. If Fuller is correct, then the exegetes who point to examples of Hammett’s radicalism in his work are simply eager to be prescient. The nihilism in Hammett’s stories, particularly in the many published in the pulp magazine Black Mask, is a product of looking upon capitalism with a jaundiced eye. That, Fuller insists, does not make the author a political radical; it just means that Hammett harbored no illusions about the prevailing socioeconomic system, or about anything else for that matter.

Fuller’s research is truly impressive. His readings include not only all of his subject’s published works, but the unpublished ones as well. He examines, by way of example, the unpublished story “The Hunter.” The story’s detective, explains Fuller, “is a nihilist and so, we must suspect, was Hammett, as he had rejected religion and as yet believed in nothing which might give his life meaning” (56). In support—and clearly such a suspicion requires support—Fuller argues that the story illustrates “what a heartless economic system will cause people to do to each other” (56). At the same time, to Fuller, “The Hunter” is a graphic example of the bleakness in Hammett’s fiction. What is certain is that for an unpublished story, “The Hunter,” as Fuller reads it, is a trove of meaning. Indeed, Fuller brings the rigor of a scholar (or of a former trade-union official?) to both Hammett’s oeuvre and to Hellman’s biographies. We are given to understand that “The Hunter” is in no way singular; any number of Hammett’s stories might be explored in its place and would reveal similar nihilistic affinities. In addition, Fuller offers in-depth critiques of Hammett’s novels: Red Harvest, The Dain Curse, The Maltese Falcon, and The Glass Key. These appraisals include detailed plot outlines, character descriptions, and style judgments, often illustrated with quotations. The purpose of each examination is to uncover what the work discloses about Hammett’s philosophical outlook.

Red Harvest, published in 1929, is Hammett’s first novel. Given that the Continental Op is tasked with cleaning up a corrupt town, a number of biographers take the tale as Hammett’s Marxist exposure of capitalism. “…[I]t is certainly a denunciation of capitalism,” Fuller concedes, “but not a Marxist one” (69). The Op, once he has been targeted by one of the town’s several black hats, sets out to drain the swamp, but for purely personal, rather than political, reasons. Fuller insists there is no evidence that “by the late 1920s Hammett had progressed beyond the bleak nihilism” that informed his magazine stories (72).

Claiming Hammett to be, as the title depicts, a hardboiled activist hardly means he was a Marxist. Yet Fuller’s methodical exploration of Hammett’s development brings him to the conclusion that his subject did in fact adopt Marxism.

The Spanish Civil War in 1936 and 1937 undoubtedly had a strong impact on Hammett’s view of the world. Breaking with the persistent feeling that nothing of consequence mattered, the war was a cause that, at last, mattered to him intensely. By this time, he was writing screenplays and spending protracted periods in Hollywood. There, he attended meetings of pro-Republican organizations and became active in anti-fascist groups. Fuller explains that Hammett “now found the world perfectly comprehensible. At last, life had meaning. His nihilism was in abeyance and he had found something in which to believe; he would cling to his new vision for the remainder of his life” (216).

Was it Spain alone that radicalized Hammett? Some biographers attribute his transformation to Hellman. However, in An Unfinished Woman, her 1969 memoir, Hellman writes: “It saddens me now to admit that my political convictions were never very radical in the true, best, serious sense” (Lillian Hellman, An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir [Boston: Little, Brown, 1969], 118). Fuller is skeptical that Hellman’s influence moved Hammett to the left. What seems more likely is that Hammett had been immersed in nihilism for so long that he desperately needed to welcome life again. He had observed the suffering caused by capitalism; a suffering that had been a feature of much of his work. Seeking solutions to such widespread wretchedness, he began to read Marxist-Leninist literature. The search itself indicates that his life was beginning to acquire purpose. The war in Spain confirmed his trajectory and gave it urgency.

The remaining question is whether Hammett formalized his Marxism by joining a party or organization. While, according to Fuller, “there is little evidence of Hammett’s party membership,” it is known that he led Marxist study groups in Hollywood, strongly suggesting a connection to the U.S. Communist Party (210). Unsatisfied with simply an indication, Fuller, ever meticulous, went to great lengths to track down and speak with Hammett’s granddaughter, Julie Rivett. In one of her conversations with Fuller, Rivett assured him that her mother remembered Hammett showing her his Communist Party membership card. Despite the scarce evidence, a former trade-union official from London was able to verify that Hammett was, in fact, an organized communist.

Anyone wishing to learn about detective-story writer Dashiell Hammett need venture no farther than this excellent book. Anyone wishing to learn about biographer Ken Fuller only need to look him up the next time they find themselves in the Philippines.

Comments are closed.