In addition to old-age benefits, it is often forgotten that Social Security provides survivor and disability insurance protections as well. The privatization debate has overlooked the fate of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) as a part of the program’s family of benefits.

I’ll wager that most Americans are unaware of the importance of SSDI, especially young workers who are the target of Bush’s campaign to divert funds into private stock market accounts.

I, too, was unaware until the late 1980s, when I found myself unable to work with an eight-year-old child to support. I had worked to put myself through college and made a career in the film industry. Even though I was born with cerebral palsy it never occurred to me that someday I might not be able to continue to work due to complications from my impairment. According to the Social Security Administration three in ten Americans have a chance of becoming impaired before reaching age sixty-seven, able-bodied or not.

I had been paying into SSDI, which today amounts to about one percentage point of the 6.2 percent total payroll tax deducted from one’s salary, and had worked sufficiently long so that when faced with a bodily breakdown I could apply for disability benefits. Disability is placed in the same framework established for the old-age program. Like retirement, SSDI is a wage earner social insurance. It is calculated based on wages earned over the number of years worked; it is not a personal investment account. If one becomes unable to engage in “substantial gainful activity” due to impairment, SSDI is there to furnish income in place of wages, as opposed to a 401(K), for instance.

SSDI won’t be there in any meaningful form, however, if President Bush dupes the public into believing that Social Security is in “crisis,” it is about to become “bankrupt,” and the solution is an “ownership society” that promotes privatization—a proposal that could siphon a larger portion of the payroll tax revenue out of the retirement fund into private investment accounts.

The Bush administration could deliver a blow to the Disability Insurance Trust Fund (a separate account in the United States Treasury) just as it plans for the retirement fund. The President’s Committee to Strengthen Social Security report entitled “Strengthening Social Security and Creating Personal Wealth for All Americans” states that SSDI program outlays are projected to increase as a percent of payroll by 45 percent over the next fifteen years, and SSDI’s costs will exceed its tax revenue starting in 2009. In other words, the committee’s view is that the disability fund is in “crisis” as is the retirement fund.

Despite Bush’s sales-pitch assurances that benefits will not be cut, a leaked private White House memo to conservative allies strongly argues that Social Security benefits paid to future retirees must be significantly reduced to make the plan work.

The committee’s blueprint, in fact, cuts disability benefits along with retiree benefits to help pay for the cost of private accounts. The projected two trillion dollar shortfall over the first decade alone resulting from the carve-outs from payroll tax revenue to pay for private accounts must either be paid for by cutting benefits or added onto the record deficit if current benefits continue to be paid.

In Bush White House doublespeak, the committee’s report cautioned that the disability benefit reductions shouldn’t be viewed as a “recommendation,” but said “in the absence of fully developed proposals, the calculations carried out for the commission and included in this report assume that defined benefits will be changed in similar ways for the two programs.” If the disability insurance elements of the program were insulated from benefit cuts, then much larger cuts in retirement benefits would be necessary to achieve the same overall level of cost reductions—reductions which are necessary because of the loss of the trust funds’ revenue to the individual accounts.

The sums are not insignificant. Already benefits to future retirees could be slashed by as much as 40 percent. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, one Bush plan being tossed around to “save” Social Security—price indexing—would result in a 46 percent drop in Social Security benefits for the average worker who retired in 2075 as compared to current law.

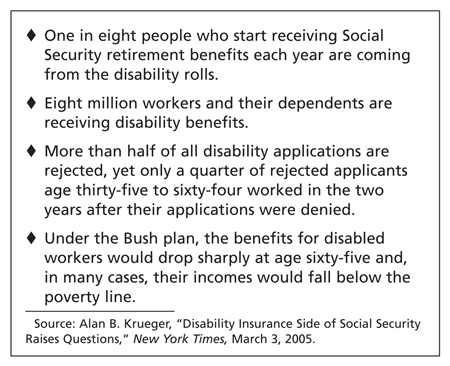

Currently retirement benefits are matched to changing wage levels but tying Social Security to an inflation index could significantly cut retirement benefits for all working Americans since inflation usually grows at a slower rate than money wages (that is, real wages tend to rise over time). SSDI is run like the retirement program, so it is likely that it too could be switched to an inflation index lowering the already meager disability benefits to levels one cannot survive on. In December 2004, for instance, the average disability benefit was a chintzy $894 per month (see the figure below for more on this theme).

There are more ways SSDI regulations could be manipulated to cut benefits and dismantle the system. The Bush administration could make eligibility rules more restrictive by changing the definition of “disabled” or make formula changes that reduce benefits. It could use Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs), which determine whether a disabled person can work, to purge disabled people from the rolls, increase the number of work credits required to qualify, and eliminate the annual cost of living adjustments.

Already SSDI can be extremely difficult to obtain owing to denials and the need to appeal one’s claim. Too often lawyers must be hired to do battle with the Social Security Administration. The process is rife with undue stress and economic hardship. Some applicants are made to wait one to two years for a final determination. Bush’s “ownership society” does not apply to them. After these applicants lose their jobs and while they wait for SSDI, the former workers’ homes are often foreclosed on and they lose their cars and savings. Many become homeless and live on the streets due to eligibility process flaws and delays. It is a degrading adversarial process. Some cannot deal with the fear of falling financially and commit suicide. All these chronically ill persons must wait two years to be covered by Medicare.

As Linda Fullerton of the Social Security Disability Coalition explained in her Congressional testimony (September 30, 2004), “the current SSD process seems to be structured in a way to be as difficult as possible in order to suck the life out of applicants in hope that they give up or die in the process, so that Social Security doesn’t have to pay them their benefits.”

It is well known that in 1981 President Reagan proposed cutting retirement benefits to shore up the retirement fund. Less known is that the Reaganites, hoping to save billions of dollars, arbitrarily sent tens of thousands of disabled people CDR notices that they were no longer “disabled,” and cut off their benefits entirely. This paper crackdown on eligibility (without due process) resulted in extreme hardship and in many instances death, sometimes by suicide, since the disability check was the only source of income for impaired people who could not work. The government has done nothing to compensate the victims of its deliberate negligence. It was as if the people whose benefits had been cut off had simply been deemed disposable. When Legal Aid attorneys sought an injunction against the head of the Social Security Administration, a judge in California stopped the Reagan savagery.

In a double whammy to the SSDI program, according to the minority staff of the House Ways and Means Committee, President Bush’s committee also recommended that access to disability accounts prior to retirement age be barred. This means not only reduced Social Security benefits, but also no money from the accounts to cushion the loss. Such a change would defeat the purpose of SSDI entirely.

The hard-right conservatives might say that the market, through private disability insurance, can pick up the pieces. But there is no private insurance plan that can compete with a social insurance program such as SSDI in covering disabled workers. For a twenty-seven-year-old worker with a spouse and two children, for instance, Social Security provides the equivalent of a $353,000 disability insurance policy. The vast majority of workers would be unable to obtain similar coverage through private markets.

According to the General Accounting Office (GAO), in 1996, only 26 percent of private-sector employees had long-term disability coverage under employer-sponsored insurance plans. Work-related coverage has been shrinking not expanding since then. It is not unheard of that after forty years of paying into private disability insurance the insurer refuses to recognize impairment as incapacitating and denies a claim.

Last November, for instance, UnumProvident reached a tentative settlement with the insurance regulators of several states, which required UnumProvident and its subsidiaries to reconsider more than 200,000 long-term disability claims which had been terminated or denied from January 1, 1997, to the present. The regulators levied a $15 million fine and instructed the insurer to review its claim handling practices. Investigations focused on assertions that UnumProvident had improperly denied claims for benefits under individual and group long-term disability insurance policies. They concluded that UnumProvident had committed numerous violations of its obligation to fairly administer claims.

How about the prospect that private investment accounts could replace lost SSDI benefits? In January 2001, after examining a number of privatization plans, the GAO concluded, “the income [from workers’ individual accounts] was not sufficient to compensate for the decline in the insurance benefits that disabled beneficiaries would receive.”

This is in part because balances would accumulate over much shorter periods of time than retirement accounts and would, therefore, provide much less income in the event that a worker becomes disabled.

Indeed it is illusory to believe that the majority of able-bodied or working disabled persons fit the profile of a worker with a lifetime of continuous work (and thus enough gains) to build “savings” accounts. Current labor market realities make staying employed a significant challenge, with workers being forced into many different jobs with long intervals of unemployment.

At the end of 2004, 6,198,000 persons depended on SSDI. Disabled workers and their family members together comprise almost eight million on the program.

The Disability Insurance Trust Fund was created with passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1956 in large measure due to efforts by organized labor—the AFL and CIO—to protect workers as capitalists used up workers’ bodies and cast them aside. Business, especially the insurance industry, was dead set against it. Today business is among the biggest supporters of privatization. The Business Roundtable (a group of blue-chip U.S. companies including Coca-Cola, Exxon Mobil, and IBM), the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Federation of Independent Business, the National Restaurant Association, and the National Association of Manufacturers all contend that individual accounts will stave off a payroll tax hike in the future, and they are anteing up millions of dollars to buy Bush’s revamping of the safety net.

There are other class relationships involved. Going back to Marx’s theory of absolute impoverishment, Ernest Mandel clarified Marx’s observation that capitalism “throws out of the production process a section of the proletariat: unemployed, old people, disabled persons, the sick, etc.” Marx described these groups as part of the poorest stratum “bearing the stigmata of wage labor.” Mandel reminded us, “this analysis retains its full value, even under the ‘welfare’ capitalism of today.”1

Indeed SSDI is part solution and part problem for workers who can no longer work. American capitalism oppresses those who cannot work by shifting them onto a poverty-based social insurance program rather than allowing them a dignified stipend. Disablement generally equates with poverty so becoming a nonworker translates into a life of financial hardship, whether one has insurance or not, and generates a very realistic fear in workers of becoming disabled.

Some social analysts describe the disability benefits system as a privilege, because it grants permission to be exempt from the work-based system. Conservatives used to describe the disability system as part of the moral economy. Neither privilege nor morality theories, however, adequately describe the function of the disability benefits system.

This “privileged” or “moral” status does not grant disabled individuals any objective right to a decent standard of living. Retirees’ benefits are higher overall than those of disabled persons on SSDI. Disability benefits hover at what is determined an official poverty level. For fiscal year 2004, the federal poverty guideline for one is $9,310. The average monthly benefit that a disabled worker receives from SSDI is $894. Average monthly benefits for disabled women are $274 lower than men’s. Income is even less if one is disabled at the bottom of the social strata with no work history or not enough quarters of work to qualify for SSDI. This group of disabled persons must apply for the welfare (needs-based) disability program, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), where the average federal benefit is $417.20 per month.2

The depth of poverty those on disability benefits face, however, cannot be accurately described without explaining that the current system of measuring poverty dates back to the 1960s. Government has never adjusted the equation to take into account the sharp rise in costs of housing, medical care, and child care over the last four decades, which have dramatically altered the average household’s economic condition. The Urban Institute concluded that, in order to be comparable to the original threshold, the poverty level would have to be at least 50 percent higher than the current official standard. If basic needs were refigured to the modern market, almost a quarter of the American people would be deemed to be living in poverty.3

In my book, Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract, I attempted to show how public disability benefits fit into the machinations of production and wealth accumulation.

At base, I wrote, the inadequate safety net is a product of the owning class’s fear of losing control of the means of production. The all-encompassing value placed on work is necessary to produce wealth. The American work ethic is a mechanism of social control that ensures capitalists a reliable work force for making profits. If workers were provided with a federal social safety net that adequately protected them through unemployment, sickness, impairment, and old age, then business would have less control over the work force because labor would gain a stronger position from which to negotiate their conditions of employment, such as fair wages, reasonable accommodations, and flexible work hours. American business retains its power over the working class through a fear of destitution that would be weakened if the safety net were to actually become safe. This, in turn, causes oppression for the less-valued nonworking disabled members of our society; those who do not provide a body to support profit making (for whatever reason) are relegated to extreme economic hardship.

What other machinations are in play? The definition of disability is flexible, for one. The corporate state defines who is “disabled” and controls the labor supply by expanding or contracting the numbers of persons who qualify for disability benefits, often for political and economic reasons. A downturn in the business cycle is disastrous for workers because there are fewer jobs to be had. It is no surprise that a recession is accompanied by an increase in the numbers of persons applying for disability benefits. Furthermore, impaired workers are the last to be hired and the first to be fired at the slightest downturn of the economy.

The conservatives’ plan to drain payroll tax revenue from the program through privatization is one way to make the little people pay for Bush’s tax cuts for the rich. It will also enrich Wall Street with a guaranteed influx of new clients buying stocks and bonds with their Social Security money—a substantial boon for financial corporations. But it is no less an effort to make workers less secure by undermining the social commitments made with the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935 and the creation of Social Security Disability Insurance, already inadequate when it was instituted in 1956. Private accounts would undermine the guaranteed benefits that are the foundation of Social Security. The Bushites want it both ways: to super exploit the work force and create a you’re-on-your-own society that would deprive workers of the security and social compensation owed them. If the privatizers succeed, able-bodied and disabled workers will be made poorer. Under a privatized system, workers may only get out what they put in, unlike the current more progressive Social Security formula that provides guaranteed and proportionally higher benefits to lower earners. Investment accounts that rely upon a shifty stock market can rob workers of every penny saved.

As of this writing there is no final Bush proposal on the table. To squelch criticism and cool dissent Bush has recently stated that he will not cut disability benefit checks. And perhaps he won’t directly go after SSDI, not now at least, because the first goal is to start the process of dismantling Social Security by convincing Americans they will be better off with private investment accounts. Building a groundswell for undermining SSDI has been a long-term endeavor, however. Reagan, for instance, aside from severing disabled persons from the rolls, tried to fold SSDI into a social service block grant to the states, which would have effectively eliminated the entitlement. In 1980, President Carter’s secretary of Health, Education and Welfare stated, “disability is killing us,” as the Carter administration succeeded in putting a cap on disability benefits and changing the way benefits were calculated to lower payments.4

Over the years, hard-right critics of SSDI have deemed it rife with fraud. Congresspersons have spoken of the dilemma of disability “dependency” and accused the program’s growth of being out of control. One reason that Republicans supported the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 was to provide protections against employment discrimination so that disabled persons would get off the dole and into jobs (this hasn’t worked but that is a topic for another time).

The current Bush administration’s approach is likely to be indirect, by making changes to regulations. For instance, there is already a plan afloat to require that those on SSDI reapply every two years—an arduous task that some may not manage well resulting in their disqualification from the program. In addition, the success of social insurance depends upon the widest pooling of risk. If the privatizers succeed, as money is diverted into private accounts, there will be less in the common pool of funds that comprise retirement and disability benefits. Disability payouts will then appear to be taking a larger piece of the pie, making the SSDI program an easy target for the hard right.

Economics, however, is not the prime motive behind the push to privatize our public commonwealth. Bush has admitted that privatization will not make Social Security solvent. The reasons are political and ideological. The White House memo mentioned earlier stated, “For the first time in six decades, the Social Security battle is one we can win—and in doing so, we can help transform the political and philosophical landscape of the country.”

Hard-right conservatives have been working since the New Deal’s inception to kill off Roosevelt’s vision—no matter that it has been a success story. In the early 1980s, free-market conservatives such as the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation began to hammer out the free-market manifestos that laid the groundwork for the current campaign. Now, the Bush administration is forcing us to defend the Social Security system that conservatives despise so much, rather than fighting to improve it. It is an all out assault. Newt Gingrich called one strategy “starve the beast”—drive up the deficit then use that as justification to cut the safety net. Privatization is the next step of a calculated, long-term campaign to end Social Security. We must do all we can to see this doesn’t happen to our children.

Notes

- ↩ Ernest Mandel, Marxist Economic Theory, vol. 1 (London: Merlin Press, 1962), 51.

- ↩ For data on benefits see http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/FACTS/fs2004_12.html; http://www.socialsecurity.gov/cgi-bin/awards.cgi; and http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/2004-12/

table1.html. - ↩ Patricia Ruggles, Drawing the Line: Alternative Poverty Measures and their Implications for Public Policy (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 1990).

- ↩ Edward D. Berkowitz, Disabled Policy: America’s Programs for the Handicapped (Cambridge University Press, 1987), 118, 121.

Comments are closed.