Also in this issue

Books by Samir Amin

Imperialism and Unequal Development

by Samir Amin

Eurocentrism

by Samir Amin

Only People Make Their Own History

by Samir Amin

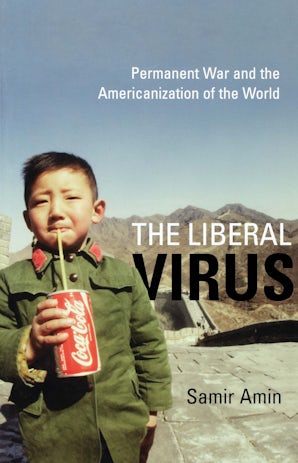

The Liberal Virus

by Samir Amin

Article by Samir Amin

- The New Imperialist Structure

- Toward the Formation of a Transnational Alliance of Working and Oppressed Peoples

- The Communist Manifesto, 170 Years Later

- Revolution or Decadence? Thoughts on the Transition between Modes of Production on the Occasion of the Marx Bicentennial

- Revolution from North to South

- The Kurdish Question Then and Now

- Reading 'Capital', Reading Historical Capitalisms

- Contemporary Imperialism

- Saving the Unity of Great Britain, Breaking the Unity of Greater Russia

- Latin America Confronts the Challenge of Globalization: A Burdensome Inheritance