Over the past six years, more than 100,000 people, including children, have been jailed in Canada, many without charge, trial, or an end in sight, merely for being undocumented. For those whose countries of origin will not accept them or issue travel documents, detention is indefinite. Locked away from the public eye, they become invisible.

Like the people within, immigrant detention centers are often invisible as well. Photos and drawings of these places are rarely public; access is even more limited. Canada has three designated immigrant prisons, and it also rents beds in government-run prisons to house over one-third of its detainees.

Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention begins to strip away at this invisibility. In graphic novel form, Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist tings chak draws the physical spaces of buildings in which immigrant detainees spend months, if not years. In crisp black and white lines, chak walks the reader through the journey of each of these 100,000+ people when they first enter an immigrant detention center.

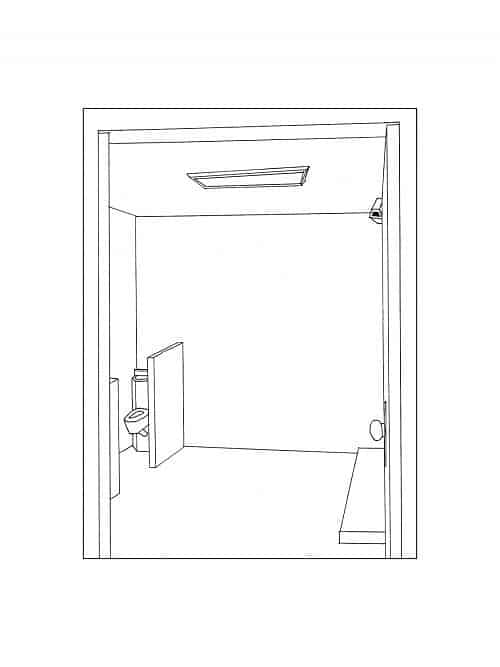

Each drawing is stark and sparse, reflecting the harshness of the surroundings. A door leading into the prison with a surveillance camera directly overhead opens to reveal another door and another camera. The reader cannot help but feel the barrenness of existing in such a place. Every glimpse, as the reader tours the prison, is devoid of life. Neither people nor possessions clutter the frames.

The tour is accompanied by single lines of dialogue. “I ask you, ‘How do you sleep at night?'” the unnamed narrator asks as the reader sees, and then moves past, the processing center, where several computer screens line a cubicle area, under the constant eye of a surveillance camera (40). It could be the reception area of a hospital. But the austerity of chak’s drawing makes it clear that it is not.

“You lean back and say, ‘I sleep well. My conscience is quiet'” (42). The reader, in the meantime, has walked to the door leading to the holding cell. The door swings open to reveal a bench and a toilet. And, of course, a security camera.

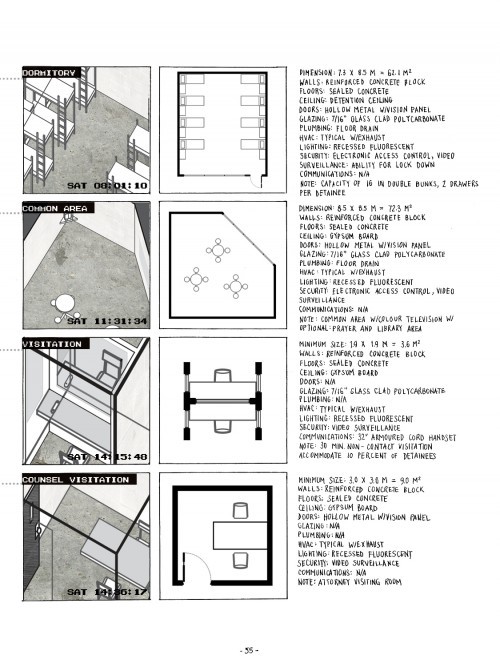

The tour continues. As the unnamed architect justifies designing the detention center, readers are confronted with his work: a dormitory that can hold sixteen people in a sixty-two meter (or 203 square foot) area using double bunks (55, 58); the common area; a visiting room where a chair faces a grill and a phone lays beside it; and the segregation units (or solitary confinement) in which a person spends twenty-three hours a day alone in a 3.6 by 3.3 meter (or twelve by eleven foot) cell (75–79).

chak’s drawings, haunting in her use of bare lines and lack of frills, are of an unidentified detention center in Canada. At the end of the tour, however, readers learn that the dialogue is actually between Israeli artist Nir Evron and the (unnamed) architect who designed the Nahal Raviv Detention Centre in Israel (85). Opened in early 2014, it was built specifically for migrants crossing the Egyptian border, three miles away. While the dialogue is specifically from Evron’s “Playing a Role,” the justifications could be uttered by architects who design prisons and immigrant detention centers anywhere around the world. After all, as chak explains in her own words, “Embedded in the politics of visibility, architecture has as much to do with the built reality as it does with representation” (26).

While Undocumented examines immigrant imprisonment in Canada, the questions chak raises—and the architecture she reveals—are just as relevant in the United States where a Congressional mandate requires that nearly 32,000 beds in immigrant detention centers be filled on any given day. In comparison, Canada, which last year deported 13,000 people and detained 8,838 more (289 of whom were children), seems less crisis-like (27). However, although these numbers are lower, detention still wreaks havoc on the individual people and their families caught in the system, as chak illustrates.

One sequence is particularly haunting in its depiction of the distortions of everyday life behind bars: “Each morning, a school bus drives up to the immigrant detention centre.” (Here, readers see the doorway and gate of the detention center. In the next frame, a young child peaks out through the window of the bus. Her head does not reach half the height of the window frame.) “Behind barbed wire and a security gate, children board the bus.” (The bus has moved behind the prison’s cyclone fence. chak draws a closer view of the child’s face.) “It becomes a ritual that spells trauma.” (The bus pulls away from the center. The reader only sees a portion of the child’s eye.) (93)

Detention also affects families by tearing them apart: “I have missed three of my son’s birthdays,” says another man. “I missed three anniversaries with my wife.” chak shows this absence through sequences of the life he is missing—three pictures of a boy, each year a little taller and less chubby-cheeked, blowing out an increasing number of candles on his birthday cake. Another sequence shows a wife eating dinner, sleeping, and sitting on the couch with an absent spouse. She says, “I cannot see myself here being detained indefinitely and thinking about them. That will drive me crazy. So I have to keep it out of sight and out of mind. How inhumane is that” (94).

Similarities between conditions in U.S. and Canadian prisons are striking. So too are the forms of resistance. In July 2013, over 30,000 people imprisoned across California launched a mass hunger strike. Among their demands was an end to the indefinite use of solitary confinement for those labeled as gang affiliates. The strike lasted sixty days.

On September 17, 2013, eight days after the California strike ended, 191 immigrant detainees in Central East Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison which also houses immigrant detainees in Ontario, refused to eat their meals or attend detention reviews. Some had been imprisoned for nearly a decade without charge or trial. One of their demands was an end to indefinite detention (110–11). While most people quickly dropped off the strike, eight persevered—one refused food for sixty-five days. One year later, some have been deported and some released but approximately one hundred of the 191 are still imprisoned in Central East.

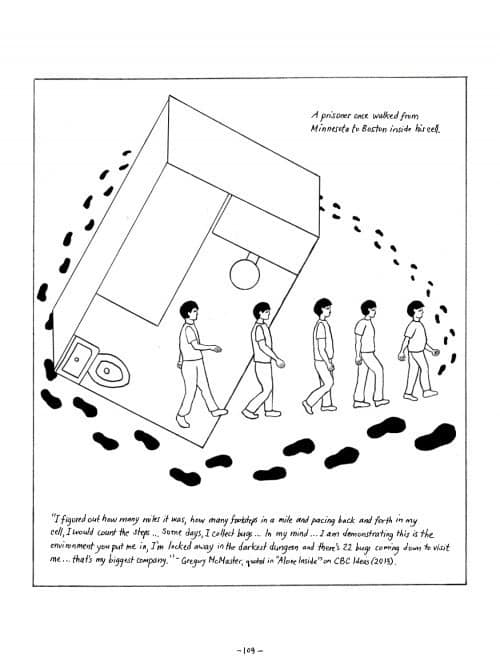

chak includes other examples of resistance. At Ontario’s Vanier Centre for Women, women resist the everyday dehumanization of detention. They tape photos onto the otherwise bare walls, hoard food, and hang toilet paper as curtains to gain a modicum of privacy from the ever-watching eyes of both staff and surveillance cameras. They find ways to turn packages of cookies, peanut butter, and M&Ms into a cake to celebrate birthdays or the release dates of women going home (106). In another detention center, a man escaped his solitary confinement cell by walking from Minnesota to Boston. “I figured out how many miles it was, how many footsteps in a mile and pacing back and forth in my cell, I would count the steps,” he recounted (109).

“How do we make visible the sites and stories of detention, bring them into conversations about our built environments, frame immigration detention as an architectural problem?,” chak asks (26). Architecture alone does not inflict these atrocities on individuals and families. But because of their distances and their seeming impenetrability, the physical buildings themselves are considered much less frequently than the policies that enable them. By focusing on these prisons’ physical layouts, Undocumented exposes the violence that architecture can inflict on those imprisoned within. Against these cold environments, the human resistance against dehumanization and despair becomes much more poignant.

“Mass incarceration is a modern idea,” proclaims chak. “We can unlearn and re-imagine, and design a world without prisons” (31). Undocumented is a good start to challenging architects—both present and future—to begin these processes of unlearning, reimagining, and designing that world.

Comments are closed.