1. Insights from the Sweezy-Schumpeter Debate

In February 2011, while I was drafting what was to become “Monopoly and Competition in Twenty-First Century Capitalism,” written with Robert W. McChesney and R. Jamil Jonna (Monthly Review, April 2011), I decided to take a look at Paul Sweezy’s copy of the original 1942 edition of Joseph Schumpeter’s Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, which I had in my possession. In doing so, I came across a folded, two-page document, “The Laws of Capitalism,” tucked into the pages. It was written in ink in Sweezy’s very compact handwriting. In the upper-right-hand corner, Sweezy had jotted (clearly much later) in pencil: “(A debate with J.A.S. before the Harvard Graduate Students’ Economics Club, Littauer Center, probably 1946 or 1947.)” The document consisted of a detailed outline, in full sentences, of a contribution to a debate. I immediately realized that this was Sweezy’s opening talk in the now legendary Sweezy-Schumpeter debate. Until that moment, I, along with everybody else, assumed that no detailed records of the actual talks had survived.1

Early in the winter 1946-47 term, the Socialist Party of Boston wrote to the Harvard economics department, proposing a debate on capitalism and socialism. The department turned the letter over to Schumpeter, who replied that the classroom was an inappropriate place for such an exchange, but said that he would arrange for the Harvard Graduate Students’ Club to sponsor the event. The Graduate Students’ Club, however, declined. Nevertheless, the debate was held, in the end, without a sponsor, with Sweezy and Schumpeter as the two protagonists, before a packed audience in Harvard’s Littauer Auditorium.2

Decades later, Paul Samuelson, writing in the April 13, 1970, issue of Newsweek, remembered it as an occasion of almost mythic proportions:

Recent events on college campuses have recalled to my inward eye one of the great happenings in my own lifetime. It took place at Harvard back in the days when giants walked the earth and Harvard Yard. Joseph Schumpeter, Harvard’s brilliant economist and social prophet, was to debate Paul Sweezy on “The Future of Capitalism.” Wassily Leontief was in the chair as the moderator and the Littauer Auditorium could not accommodate the packed house….

Let me set the stage. Schumpeter was a scion of the aristocracy of Franz Joseph’s Austria….Half mountebank, half sage, Schumpeter had been the enfant terrible of the Austrian school of economists. Steward to an Egyptian princess, owner of a stable of race horses, onetime Finance Minister of Austria, Schumpeter could look at the prospects for bourgeois society with the objectivity of one whose feudal world had come to an end in 1914. His message and vision can be read in his classical work of a quarter century ago, “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.”

Opposed to the foxy Merlin was young Sir Galahad. Son of an executive of J.P. Morgan’s bank,3Paul Sweezy was the best that Exeter and Harvard can produce….Sweezy had early established himself as among the most promising economists of his generation. But tiring of the conventional wisdom of his age, and spurred on by the events of the Great Depression, Sweezy became one of America’s few Marxists….

Unfairly, the gods had given Paul Sweezy, along with a brilliant mind, a beautiful face and wit. With what William Buckley would desperately wish to see in his mirror, Sweezy faced the world. If lightning had struck him that night, people would truly have said that he had incurred the envy of the gods.

So much for the cast, I would have to be a William Hazlitt to recall for you the interchange of wit, the neat parrying and thrust, and all made the more pleasurable by the obvious affection that the two men had for each other despite the polar opposition of their views.4

In order to understand this legendary debate and its historical significance, it is necessary to know something about the intellectual and personal relations between the two protagonists. Sweezy and Schumpeter first met in the fall of 1933. Sweezy, who had done his undergraduate work in economics at Harvard, had just spent a year studying at the London School of Economics, and was returning to do graduate work at Harvard—now deeply influenced by his initial exposure to Marxist thought. In the meantime, Schumpeter had accepted a post as professor of economics at Harvard. Although Sweezy was never in any real sense Schumpeter’s student, he joined a small seminar on economic theory led by Schumpeter, consisting of around five participants in which Wassily Leontief, Oskar Lange, and Elizabeth Boody (later to be Schumpeter’s wife) also took part. Schumpeter was unique among the Harvard faculty in that his entire system of economics reflected a serious engagement with Marx’s thought, although his own conservative views were diametrically opposite. He paid Marxism the compliment of considering it to be perhaps the most important intellectual movement of the day. Schumpeter’s classic work, The Theory of Economic Development (1911), was written with an aim that he saw as similar to that of Marx, in the sense of providing “a vision of economic evolution as a distinct process generated by the economic system itself.”5

Sweezy and Schumpeter soon became close personal friends—part of a social as well as intellectual community in Cambridge at the time. For two years in the mid-1930s, Sweezy was Schumpeter’s assistant in the latter’s introductory graduate economics theory course. Their relationship, however, was more personal than intellectual. As Sweezy explained in a letter to his friend, the economist Sol Adler (September 29, 1987), “As to my relationship with Joe, I don’t know if there is much of real interest. In an intellectual sense, there wasn’t much to it. I was curious about and interested in his theories but I think hardly at all influenced by them. We never discussed such matters at any length. The personal relationship was something else but not at all easily described or classified. Perhaps I was something of an ersatz son—incidentally, if I was his Harvard ersatz son, Taussig was his ersatz Harvard father—and we were certainly very fond of each other.”6 Their close connection lasted until Sweezy joined the army in 1942—the year that Sweezy’s The Theory of Capitalist Development and Schumpeter’s Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy were published.

Sweezy’s The Theory of Capitalist Development derived its title from Schumpeter’s The Theory of Economic Development, symbolizing the complex, dialectical relation between two very different views of economic development.7 The Theory of Economic Development starts with Schumpeter’s famous concept of “the circular flow.” This is an economic process in which there is no growth—and from which the entrepreneur, who, for Schumpeter, is the source of all economic development, has been abstracted. In Schumpeter’s conception of the circular flow, consumption is the primary motive of economic activity, profit and interest are absent, and the whole economy conforms to a perfectly (or freely) competitive model (largely in line with Walrasian general equilibrium theory). Society consists of two classes: landlords (who receive rents) and all others. Everyone has equal access to “capital.” Employees can turn themselves into employers, if they wish. The assumptions of Schumpeter’s model are more than sufficient to generate a stationary economy. But they also remove all the institutional features of capitalism. By then introducing the innovating entrepreneur into this static model, Schumpeter was able to argue that the entrepreneur is the source of all economic development and the business cycle.8

In contrast, Sweezy’s account of Marxian political economy in The Theory of Capitalist Development argues that accumulation, as opposed to the entrepreneur, is the prime mover of the economy, and that the logic of the system runs from accumulation to innovation, and not the other way around. In Marx’s reproductive schemes at the end of volume 2 of Capital, a model of the economy, referred to as “simple reproduction” is presented, from which all development is abstracted. All the institutional characteristics of capitalism remain, but the assumption is made that all surplus is consumed through increased capitalist consumption, rather than invested in the form of new net investment (which does not exclude replacement investment out of depreciation funds). This creates an economy that simply reproduces itself at the same level, year in and year out. Yet Marx’s whole point is that this is, in reality, impossible for any length of time in a capitalist system, whose credo is “Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets.”9 Hence, he quickly turns from the abstract model of simple reproduction, to the more realistic model of “expanded reproduction,” in which accumulation takes place.

As Sweezy summed up the difference between the Marxian and Schumpeterian systems in his article “Professor Schumpeter’s Theory of Innovation” (published in 1943 in honor of Schumpeter’s sixtieth birthday), for Schumpeter: “Profits result from the innovating process, and hence accumulation is a derivative phenomenon. The alternative view maintains that profits exist in a society with a capitalist class structure even in the absence of innovation. From this standpoint, the form of the profit-making process itself produces the pressure to accumulate, and accumulation generates innovation as a means of preserving the profit-making mechanism and the class structure on which it rests.”10 Rather than a minor issue, this constituted the principal difference between Marxian (and classical) and orthodox or neoclassical economics.

Schumpeter’s notion of economic development, arising from the individual entrepreneur, had a certain claim to plausibility in the nineteenth-century era of free competition. But, with the rise of the giant corporation and monopoly capitalism, the ideas of both free competition and of the entrepreneur as the leading force in economic change were obviously less and less relevant. Schumpeter was the first mainstream (non-radical) economist to address theoretically the rise of a new stage of concentrated capital, in his 1928 essay, “The Instability of Capitalism,” directed at what he called “trustified capitalism”—under which firms no longer acted as competitors but rather, as what he termed “corespectors” (a reference to oligopolistic markets). Recognizing the difficulties that this presented for his analysis of the entrepreneur, he took the big step in this article of placing the innovative function, no longer in the hands of the entrepreneur, but in the big corporation, and seeing it as routinized by an army of specialists, if without the entrepreneurial dynamism of before.11 But this change in his model was little noticed in economics as a whole—until 1942, when he advanced it again in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, in the context of a conflict with New Deal economics.

The key economic argument of Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy was developed in Part II, entitled “Can Capitalism Survive?” (Schumpeter’s famous answer was: “No. I do not think it can.”) Here he was concerned with refuting New Deal criticisms of capitalism for its monopolistic and stagnationist tendencies. Although Schumpeter did not deny—in the great stagnation debate of the late 1930s and early 1940s brought on by the Great Depression—that the system was, in fact, stagnating, he insisted that the causes were more sociological than economic.

In his chapter, “Monopolistic Practices” in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Schumpeter advanced arguments designed explicitly to counter New Deal criticism of the large firm in the context of the Great Depression. Yet this defense of monopoly was weakened by his view that, while the monopolistic corporation was in some ways more efficient than its competitive predecessor, it also took the life out of the capitalist process. Here he reintroduced his notion that the corporation had now taken over the entrepreneurial function, automatizing progress. As he had noted in Business Cycles: “The mechanization of ‘progress’ may for entrepreneurs, capitalists, and capitalist returns produce effects similar to those which cessation of technological progress would have. Even now, the private entrepreneur is not nearly so important a figure as he has been in the past.”12 For Schumpeter, the vanishing entrepreneur became an explanation for capitalism’s “crumbling walls.” “Economically and sociologically, directly and indirectly,” he wrote in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, “the bourgeoisie…depends on the entrepreneur and, as a class, lives and will die with him….The perfectly bureaucratized giant industrial unit now only ousts the small or medium-sized firm and ‘expropriates’ its owners, but in the end it also ousts the entrepreneur and expropriates the bourgeoisie as a class which in the process stands to lose not only its income but also what is infinitely more important, its function.”13

Schumpeter’s approach to economic stagnation, i.e., the failure of the economy to reach a full recovery by the late 1930s, rejected the whole Keynesian analysis of effective demand associated with a tendency toward oversavings in relation to what Schumpeter dubbed “vanishing investment opportunities.” The argument here was principally directed at the work of Schumpeter’s Harvard colleague Alvin Hansen, as advanced in Full Recovery or Stagnation? (1938) and Fiscal Policy and Business Cycles (1941). Schumpeter simply denied that intended savings could, under conditions of growing capitalist maturity (where industry had been built up and capital-saving innovations had become more important), exceed profitable investment outlets. Since he saw innovation as the critical element determining investment, an analysis that viewed investment as in some sense self-limiting was one that he could neither fully understand nor fully accept.14

Paul Sweezy (on left) with literary historian and MR benefactor F.O. Matthiessen in the 1940s. Monthly Review Archives.

In contrast to an accumulation-based explanation of stagnation, Schumpeter focused instead on what Sweezy was later to refer to as a “New Deal theory of stagnation”—of the kind advanced by political conservatives generally. In this view, it was the New Deal legislation that was the primary cause of continuing economic stagnation, not the accumulation (or savings-and-investment) process. In effect, the state, by intervening in the economy and attempting “to run capitalism in an anticapitalist way,” had interfered with the entrepreneurial function, which was the key to the business cycle. For Schumpeter, the growth of anticapitalist attitudes, fed by intellectuals, was a crucial element in capitalism’s decline.15

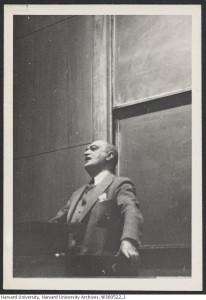

Joseph A. Schumpeter debating Paul M. Sweezy at Harvard’s Littauer Center, Courtesy of the Harvard University Archives, call # HUGBS 276.90p(40)

Schumpeter, as he indicated numerous times, admired Sweezy’s The Theory of Capitalist Development as the first successful attempt to synthesize the Marxian system in terms of modern economics. He viewed Sweezy himself as a symbol of the crisis of capitalism—an accomplished Marxian economic theorist, who challenged capitalism, particularly in relation to monopoly and stagnation.16

Sweezy, who served in the Second World War, first in the army, and then in the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and as editor of its European Political Report, was discharged from the service (with a Bronze Star) in October 1945. He had two and a half years remaining in his contract as an assistant professor of economics at Harvard prior to coming up for tenure. But, given the repressive political-ideological climate of the time, prospects for his eventually obtaining tenure—despite Schumpeter’s strong backing—were bleak, and Sweezy resigned his position in 1946, at about the time of his famous debate with Schumpeter, to take up full-time research and writing.17

All of this forms the background against which we can view Sweezy’s “Laws of Capitalism” and the entire Sweezy-Schumpeter debate. Sweezy’s detailed outline of his talk is printed below, together with commentary that I have provided to assist the reader.

Sweezy’s argument focused principally on the issue of the laws of motion of capitalism, that is, what constituted capitalism’s prime mover. For Schumpeter, as we have seen, it was the entrepreneur. For Sweezy, it was accumulation: a process that transcended the individual capitalist. For Schumpeter, all the specific economic characteristics of capitalism—profits, savings and investment, interest, the business cycle, even the capitalist, along with economic development—derived from the entrepreneurial function. For Sweezy, in contrast, the main institutional characteristics of capitalism should be seen as coming first and generating an accumulation dynamic (M-C-M′), to which innovation (Schumpeter’s creative destruction and Marx’s revolutionization of the means of production) was a response.

These different conceptions resulted in radically different theories of capitalism and crisis. In Schumpeter’s case, the business cycle was principally related to cycles of innovation; for Sweezy, it had principally to do with cycles of accumulation. It followed that for Schumpeter, crises were not essentially about failures in the accumulation (savings-and-investment) process, which tended to equilibrate on its own. While for Sweezy, it was precisely the accumulation process that was fundamentally at issue in any crisis.

Finally, there was the question of monopoly, stagnation, and the transition from capitalism to socialism. Schumpeter had argued in 1928 that “trustified capitalism” generated greater economic stability by attenuating creative destruction and hence crises (through a process of the automatization of innovation), while at the same time undermining the sociological foundations of capitalism by displacing the individual entrepreneur. Sweezy, in the debate, invited Schumpeter, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, to rethink the notion that monopoly capitalism was a force for economic stability.

In one sense, the Sweezy-Schumpeter debate was a disappointment to many of the economists and interested parties who crowded into the Littauer Auditorium that night. Schumpeter, as all of his closest friends and colleagues have noted, was extraordinarily reticent about discussing his own work and ideas in public. He simply refrained from doing so in the face of every request—in line with what was clearly a deeply felt personal and intellectual principle, which, for some reason, he never articulated.18 On this occasion too he remained true to form in this respect, and despite Sweezy’s attempt to draw him out and to erect a debate based on the differences between the Marxian (and Keynesian) and Schumpeterian systems, Schumpeter refused to respond directly by commenting on his own system of thought. As Eduard März, who was present on the occasion, wrote in his Joseph Schumpeter: Scholar, Teacher, and Statesman, “During a public discussion on the current significance of socialism, Paul M. Sweezy, then the youngest member of the Harvard economics faculty, discussed the main points of the Schumpeterian theory and asked his eminent colleague to give an opinion on some of the controversial questions expressis verbis. Schumpeter ignored Sweezy’s challenge and began a long-winded panegyric on the US economic system, paying no attention to provocative remarks from the students.”19 As Allen put it, “Schumpeter ‘lost’ the debate. Samuelson’s romanticized version of the debate does not reveal Schumpeter’s usual discomfort in propounding and defending his views. Failing to present an adequate statement of his theory of development, he allowed Sweezy to seize and maintain the initiative; on the defensive, Schumpeter then did not counteract or perform well.”20

If Schumpeter did not reply directly to Sweezy’s criticisms of his system, what was the general nature of his response? Given März’s comments, we can presume that Schumpeter concentrated on the question of the U.S. economy. He had just finished writing in July 1946 a new chapter 28 to Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, entitled, “The Consequences of the Second World War,” which dealt with the economic situation as the war ended. The new edition of his book was published in 1947, and was in press but had not yet been released at the time of his debate with Sweezy. It therefore seems a reasonable assumption that he drew from his section on “The Economic Possibilities in the United States,” and particularly from his subsection on “The Stagnationist Thesis,” as presented in that new chapter. There Schumpeter engaged in an assault—much less restrained than in the first edition of his work—on Keynes and those he labeled “stagnationists.” Specifically, he denied that there could be a persistent problem of “oversaving.” There was “nothing to fear,” he wrote, “from people’s propensity to save.” At the same time, he argued that state action and high-wage rates had produced a “dislocation of entrepreneurial planning,” weakening the real possibilities for rapid economic growth—opening the way to the eventual demise of the system.21

The electric atmosphere in the Littauer Auditorium on that occasion, however, seems to have moved the debate beyond the initial intentions of its two protagonists, leading them—in the give and take that ensued—to proffer general assessments of capitalism and the prospects for socialism. Leontief, as chair, summarized the views expressed:

The patient is capitalism. What is to be his fate? Our speakers are in fact agreed that the patient is inevitably dying. But the bases of their diagnoses could not be more different.

On the one hand there is Sweezy, who utilizes the analysis of Marx and of Lenin to deduce that the patient is dying of a malignant cancer. Absolutely no operation can help. The end is foreordained.

On the other hand, there is Schumpeter. He, too, and rather cheerfully, admits that the patient is dying. (His sweetheart already died in 1914 and his bank of tears has long since run dry.) But to Schumpeter, the patient is dying of a psychosomatic ailment. Not cancer but neurosis is his complaint. Filled with self-hate, he has lost the will to live.

In this view capitalism is an unlovable system, and what is unlovable will not be loved. Paul Sweezy himself is a talisman and omen of that alienation which will seal the system’s doom.22

Schumpeter thus referred to the growing anticapitalist influences in society as a reason for the system’s decline, playfully pointing to Sweezy himself as an example. It was this, in fact, that induced Samuelson to recall the debate in his Newsweek column in 1970, at a time when the New Left had emerged on college campuses. The Union for Radical Political Economics had been established in 1968, challenging the orthodox economics profession—with Paul Sweezy then representing a source of inspiration and guidance for a younger generation of radical political economists. For Samuelson, dismayed by the revolt in the academy, this only seemed to confirm Schumpeter’s point in the Harvard debate more than two decades earlier that the “alienation of privileged youth” constituted a threat to the system.23

One incident stood out that night in the Littauer Auditorium, contributing to the general sense of merriment. As Sweezy later recalled: “In the discussion period Elizabeth Schumpeter intervened at considerable length—I think with an argument citing Japanese experience—and I answered in mock distress, complaining that I thought it was unfair for the Schumpeter family to bring up their big guns. That brought down the house, as it was intended to do.”24 In Allen’s words, “The crowd roared [in response] and enjoyed the evening immensely.”25

Sweezy, in his later years, had no inclination to romanticize the debate with Schumpeter. Rather, what significance it had for him was simply as a part of a much larger debate on stagnation that took place from the late 1930s into the 1940s—and that had all the signs of “becoming one of the classic controversies in the history of economic thought.” The whole question of the stagnation of capital accumulation, however, was to be buried prematurely, due to the economic stimulus offered by the Second World War, followed by the relative prosperity in the early postwar years.26 Ironically, when stagnation eventually did reemerge in the 1970s and ’80s, the Schumpeterian supply-side view was to triumph over what remained of Keynesian demand-side economics.

In “Why Stagnation?”—a talk delivered to the Harvard Economics Club in 1982—and in numerous articles and books in the 1980s and early 1990s, Sweezy insisted that it was high time to resume the debate on stagnation. Hence, he continually returned (together with his Monthly Review coeditor Harry Magdoff) to the classic dispute between Keynes-Hansen and Schumpeter—as well as to the Marxian contributions to the debate in the work of Michal Kalecki and Josef Steindl, and in Sweezy’s own joint work with Paul Baran in Monopoly Capital.27

In line with this, I would argue that today, in a time of deepening stagnation, a resumption of the debate over “The Laws of Capitalism”—focusing on capitalism’s tendency to overaccumulation and stagnation—is a necessity, if we are to develop a realistic assessment of the present as history. For this, if for no other reason, the Sweezy-Schumpeter debate deserves our close attention.

2. The Laws of Capitalism

i Sweezy was here providing a light-hearted opening to the debate, saying that, by going first, he was setting up the gladiatorial combat for the “wicked” pleasure of the audience: the meaning of “Roman holiday.”

1. The “Roman holiday” reason for choosing to lead off the discussion.i

ii Here the point was that, in using the term “laws,” both Sweezy and Schumpeter were agreed that these should be viewed, in the manner of Marx, as historical “tendencies” and in a historically specific context. Thus, it was common for Schumpeter to raise the issue of “long-run tendencies” and their relation to “causes inherent in the capitalist mechanism.” See Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (hereafter, CSD), 70.

2. The genesis of the title. Schumpeter’s interpretation: “mechanisms and long-run tendencies of capitalist development.” This is just what I meant and I think makes unnecessary any methodological or philosophical discussion of the meaning of “laws.”ii

3. In the first place, he and I will probably find wide areas of agreement. Let me quote a passage from his latest book with which I entirely agree:

iii Schumpeter, CSD, 82-83. This passage was referred to in Sweezy’s outline and was marked in his copy of the book.

Capitalism…is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. And this evolutionary character of the capitalist process is not merely due to the fact that economic life goes on in a social and natural environment which changes and by its change alters the data of economic action; this fact is important and these changes (wars, revolutions and so on) often condition industrial change, but they are not its prime movers. Nor is this evolutionary character due to a quasi-automatic increase in population and capital or the vagaries of monetary systems of which exactly the same thing holds true.iii

iv In the sentence following the passage that Sweezy quoted from Schumpeter’s CSD, Schumpeter had gone on to say: “The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates” (emphasis added by Sweezy in his copy of Schumpeter’s book). Schumpeter’s argument here is that entrepreneurial innovation is the prime mover of capitalism: the very thing that Sweezy seeks to dispute.

4. But there is an important disagreement about what sets this process in motion. Schumpeter’s theory, as I understand it, is that the motor force comes from the “entrepreneur.”iv The entrepreneur is an innovator, a recognizable sociological type (“leader” type) which comes from all strata of society. The type presumably exists in other societies, but it is only in capitalism that its representatives predominantly devote themselves to the economic sphere.

v Sweezy indicates here that, in the Schumpeterian system, not only economic development is derived from the leadership of the entrepreneur in carrying out innovation (new methods and combinations of production) but that all the institutional characteristics of capitalism are derived from this too.

5. It is probably not usually realized how crucial the entrepreneur is to Schumpeter’s conception of the capitalist process. Take him away and you have the “circular flow” from which there is absent not only innovation but also many of the other most characteristic features of the system. For example, profits and interest and hence savings and investment—i.e. the most important forms of capitalist income and the typical manner of its disposal. These are derived from the activity of the entrepreneur. In addition of course, it is more generally realized that the business cycle has such an origin in Schumpeter’s theory.v

vi Here Sweezy refers to the accumulation process in Marx’s terms (see Capital, vol. 1, Part 2: “The Transformation of Money into Capital”), as a process of M[oney]-C[ommodity]-M[oney]′—with the ′ standing for the Δm or surplus value gained at the end of the exchange. Capital is thus defined as self-expanding value in which M′ in one period of production gives rise to M′′ in the next, and M′′′ in the period after that, and so on—with no end to the process. For Sweezy “M-C-M′ is the heartbeat that pumps the system’s monetary lifeblood through its arteries and veins. In the one case as in the other, the health of the system depends on the proper functioning of the heart: irregularity or weakness causes systemic illness and in extreme cases threatens life itself.” Magdoff and Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Crisis, 158.

6. Contrast to this the Marxian standpoint. Profit has its origin in the institutional structure of the economy. This in turn shapes the behavior of capitalists. Illustrate with the formula M-C-M′. The drive for profits implies accumulation and innovation. There is no reason to deny the existence of Schumpeter’s entrepreneurial type, but its significance is quite differently evaluated. For him the entrepreneur occupies the center of the stage; the accumulation process is derivative. For me the accumulation process is primary; the entrepreneur falls in with it and plays a part in it.vi

vii Sweezy’s argument here suggests that in Schumpeter’s supply-side approach, which focuses on entrepreneurial innovation as the primary cause of business cycle fluctuations, there is an implicit adoption of Say’s Law (supply creates its own demand), whereby the system automatically equilibrates (at least in the long run) with respect to savings and investment, with no contradictions arising. In this way, Schumpeter’s view stands opposed to that of both Marx and Keynes. Schumpeter argued that Keynes’s (and Marx’s) critique of Say’s Law was exaggerated, and really only related to a “special case.” See Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, 624. Indeed, Schumpeter’s main objection to Keynes was that he had provided “a doctrine that may not actually say but can easily be made to say both that ‘who tries to save destroys real capital’ and that, via saving, ‘the unequal distribution of income is the ultimate cause of unemployment.’ This is what the Keynesian Revolution amounts to.” Joseph A. Schumpeter, Ten Great Economists (New York: Oxford University Press, 1951), 290.

7. Let me go on to point out some of the consequences of these two approaches for cycle theory. Schumpeter’s theory of clustering and absorption of innovations is familiar to you. Generally speaking, it denies—or at least strongly discounts—what may be called savings-and-investment troubles. These are, so to speak, created by entrepreneurs; they are incidental to the innovation process. In principle, the economy adapts itself to the activity of entrepreneurs. They can force a high rate of saving and investment. But if they don’t, the economy will be content with a high level of consumption. In the long-run there is simply no problem here; the economy is fundamentally self-adjusting.vii

viii This argument is not only the main conclusion of the Keynesian Revolution, but is also presented here by Sweezy in a way that is integrated with the Marxian analysis of accumulation, generating a theory of overaccumulation. This constituted a direct challenge to Schumpeter’s point of view, since he explicitly downplayed “disturbances in the savings-investment process,” which he claimed it was “the fashion [in economics] to exaggerate.” Schumpeter, CSD, 120.

8. If, on the other hand, accumulation is the primary factor, this is no longer so. There is no mechanism in the system for adjusting investment opportunities to the way capitalists want to accumulate and no reason to suppose that if investment opportunities are inadequate capitalists will turn to consumption—quite the contrary. Hence, on this view, savings-and-investment troubles are endemic to the capitalist system.viii

ix Here Sweezy seems to be saying that there is no reason to suppose that the business cycle shows some mathematical uniformity between the boom and slump phases of the cycle, but that a great deal of variation is possible—precisely because accumulation (or the savings-and-investment process) is subject to all sorts of fits and starts.

9. This implies a very different view of the cycle problems. I don’t intend to go into the question, but I will say I can’t see why it is considered so important to have a uniform cycle theory. I believe there are several reasons why a boom can break down, and it is easy to explain why a depression should be followed by a revival. I would be glad to hear some discussion of this view which may even be considered heretical from a Marxist standpoint.ix

x For Sweezy, Schumpeter’s 1928 essay, “The Instability of Capitalism,” was crucial, since it raised the issue of the shift from competitive to monopoly (referred to by Schumpeter as “trustified”) capitalism, the relation of this to economic stability, and the question of the transition from capitalism to socialism. Schumpeter had concluded in this essay that trustified capitalism, in automatitizing innovation within the large corporation, had produced “the result that the only fundamental [economic] cause of instability inherent to the capitalist system is losing its importance as time goes on, and may even be expected to disappear.” In other words, the effect of creative destruction in generating big business cycle swings that destabilized the system was ebbing. Schumpeter, Essays, 71. At the same time, Schumpeter argued that the sociological foundations of capitalism were being removed, as a result of the disappearance of the entrepreneur as a social type, pointing in the direction of socialism. Although Schumpeter took up this problem again in 1942, in CSD, the economic part of the argument was not, in Sweezy’s view, developed any further, with Schumpeter failing to address consistently and coherently the relation between growing monopolization and the increasing economic instability of capitalism. Sweezy’s final point in his talk was therefore directed at getting Schumpeter to respond to the issues of monopoly capitalism, structural economic crisis, and the instability of the system as a whole. These issues were, of course, central to Sweezy’s own work, to be developed most fully in Paul M. Sweezy and Paul A. Baran, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966).

10. Finally, one more point, though I have probably started already enough hares for us to chase all evening. Already in the “Instability of Capitalism,” Schumpeter took the position that the trustification of capitalism was radically altering the nature of the entrepreneur and his traditional role in the direction of rationalizing and routinizing and institutionalizing it. This should lead to greater stability. The same view of what is happening to entrepreneurship is expressed even more strongly in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. But I submit that capitalism has not shown any signs of becoming more stable. What has Professor Schumpeter to say about this problem now? Does he regard the theory I have attributed to him as no longer applicable? If so, what takes its place? If not, how account for the apparent discrepancy between the expectation to which it gives rise and the observed facts?x

- ↩ In a January 16, 1984, letter to Schumpeter biographer Robert Loring Allen on the 1946 debate, and on other occasions in the 1980s and ‘90s, Sweezy indicated that he did not have a good recollection of the detailed intellectual content of the debate, though he had vivid memories of the event as a whole, which was, in his words, a “good-natured occasion, which everyone seemed to enjoy.” It seems reasonable to assume from this that Sweezy had forgotten all about his manuscript left in his 1942 edition of Schumpeter’s book.

- ↩ Robert Loring Allen, Opening Doors: The Life and Work of Joseph Schumpeter (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1991), 170. The information on the origins of the debate was taken by Allen from correspondence in the Schumpeter papers in the Harvard University Archive.

- ↩ Samuelson was mistaken on this point. Sweezy’s father was not an officer in Morgan’s bank but a vice president in George F. Baker’s bank, the old First National Bank of New York—one of the predecessors of City Bank. Baker was a close ally of Morgan and one of the financial giants of the early twentieth century. On Everett B. Sweezy (Paul’s father) see Sheridan A. Logan, George F. Baker and His Bank (St. Joseph, Mo.: S.A. Logan, 1981), 376-79.

- ↩ Paul A. Samuelson, Collected Scientific Papers, vol. 3 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1972), 710.

- ↩ Joseph A. Schumpeter, Essays (Cambridge: Addison-Wesley, 1951), 160.

- ↩ Paul M. Sweezy (Larchmont) to Sol Adler (Beijing), September 29, 1987.

- ↩ Paul M. Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), ix.

- ↩ Joseph A. Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961); Paul M. Sweezy, The Present as History (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1953), 267-73; John Bellamy Foster, “Theories of Capitalist Transformation: Critical Notes on the Comparison of Marx and Schumpeter,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 98, no. 2 (May 1983): 327-31.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1 (London: Penguin, 1976), 742, and Marx, Capital, vol. 2 (London: Penguin, 1978), 468-599.

- ↩ Sweezy, The Present as History, 282.

- ↩ Schumpeter, Essays, 47-72; Paul M. Sweezy, Modern Capitalism and Other Essays (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972), 32.

- ↩ Joseph A. Schumpeter, Business Cycles, vol. 2 (New York: McGraw Hill, 1939), 1034. What is known in the economic and sociological literature as the “Schumpeter Thesis,” according to which large firms are more innovative than smaller, more competitive ones, is a gross distortion of Schumpeter’s own argument both with respect to its economic specifics and even more so when taking into account his entire analysis (both economic and sociological) of the effects of the decline of the entrepreneur. For an excellent treatment see Anne Mayhew, “Schumpeterian Capitalism versus the ‘Schumpeterian Thesis,’” Journal of Economic Issues 14, no. 2 (June 1980): 583-92.

- ↩ Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1942), 134. On Schumpeter’s entire theory of the rise and decline of capitalism see John Bellamy Foster, “The Political Economy of Joseph Schumpeter: A Theory of Capitalist Development and Decline,” Studies in Political Economy 15 (Fall 1984): 5-42.

- ↩ Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, 111-20; Alvin H. Hansen, Full Recovery or Stagnation? (New York: W.W. Norton, 1938), and Fiscal Policy and Business Cycles (New York: W.W. Norton, 1941); and William E. Stoneman, A History of the Economic Analysis of the Great Depression in America (New York: Garland Publishing, 1979), 151-66. In an April 10, 1991, letter to Schumpeter biographer Wolfgang Stolper, who had asked Sweezy for comments on the manuscript of his biography, Sweezy wrote: “Perhaps my biggest difference with you (and Joe) is touched on in various passages….You both, it seems to me, identify innovations with profitable investment opportunities and draw the conclusion that since the supply of innovations is theoretically inexhaustible the same also holds for profitable investment opportunities.” Paul M. Sweezy to Wolfgang Stolper, April 10, 1991; Wolfgang Stolper, Joseph A. Schumpeter: The Public Life of a Private Man (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

- ↩ Schumpeter, Business Cycles, vol. 2, 1036-37, and Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, 145-55; Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987), 30-32.

- ↩ On Schumpeter’s view of Sweezy’s book see Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954), 392, 884-85, and Richard Swedberg, Schumpeter: A Biography (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991), 140.

- ↩ See John Bellamy Foster, “The Commitment of an Intellectual: Paul M. Sweezy (1910-2004),” Monthly Review 56, no. 5 (October 2004): 14-15.

- ↩ On Schumpeter’s enormous reticence to speak on his own theoretical contributions, even when directly requested to do so, see Paul M. Sweezy, “Introduction,” in Joseph A. Schumpeter, Imperialism and Social Classes (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1951), viii-ix.

- ↩ Eduard März, Joseph Schumpeter: Scholar, Teacher, and Politician (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 165. März does not specifically say on what occasion the debate he witnessed occurred. But he arrived at Harvard in 1941, and Sweezy was in the OSS in Europe from 1942 to fall 1945—so it is almost certain these remarks relate to the winter term 1946-1947 debate in the Littauer Auditorium. His comments, moreover, match those of other reports on the debate.

- ↩ Allen, Opening Doors, 171.

- ↩ Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, 380-98.

- ↩ Leontief quoted in Samuelson, Collected Scientific Papers, 710.

- ↩ Samuelson, Collected Scientific Papers, vol. 3, 710.

- ↩ Sweezy to Allen, January 16, 1984. That this was all in fun, especially with respect to the parties most concerned, is evident in the fact that Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter and Sweezy were also good friends, and Sweezy had played a role “witting and unwitting,” as he later said, in helping her with her plans to become more intimately acquainted with Schumpeter. When he married Elizabeth in 1937, Schumpeter wrote to Sweezy good-naturedly that (as Sweezy later recalled) “it was all my fault, damn me [laughter]. I had to disclaim all responsibility. I certainly didn’t do anything to promote it willingly.” Sweezy, Interview, Columbia University Oral History Project, December 10, 1986, session 3, 81-82. Sweezy subsequently assisted Elizabeth Schumpeter in her editing of her husband’s posthumous History of Economic Analysis.

- ↩ Allen, Opening Doors, 171.

- ↩ Magdoff and Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, 332.

- ↩ See Magdoff and Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, 7-10, 29-38, 43-45.

Comments are closed.