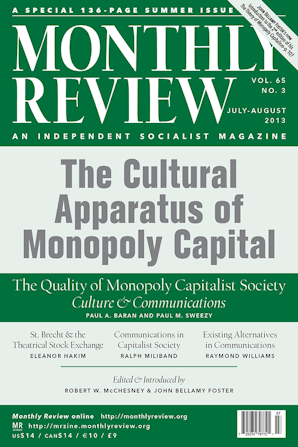

Also in this issue

- The Cultural Apparatus of Monopoly Capital: An Introduction

- Theses on Advertising

- The Quality of Monopoly Capitalist Society: Culture and Communications

- Introduction to the Second Edition of The Theory of Monopoly Capitalism

- St. Brecht and the Theatrical Stock Exchange

- The Existing Alternatives in Communications

Books by Ralph Miliband

Soc Reg’93 Real Problems

by Ralph Miliband

New World Order: Soc Reg’ 92

by Ralph Miliband

Social Register’ 83

by Ralph Miliband