Also in this issue

Books by Marta Harnecker

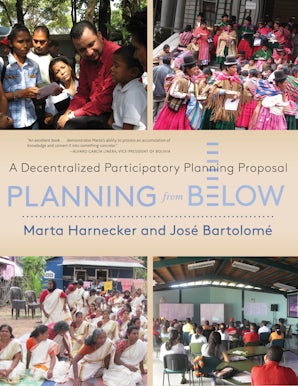

Planning from Below

by Marta Harnecker and Jose Bartolome

A World to Build

by Marta Harnecker

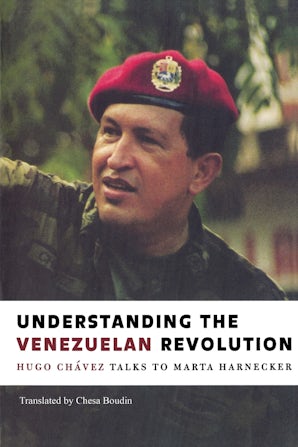

Understanding the Venezuelan Revolution

by Hugo Chavez and Marta Harnecker

Article by Marta Harnecker

- A New Revolutionary Subject

- 'A New Revolutionary Subject': Marta Harnecker interviewed by Tassos Tsakiroglou

- I. Latin America

- II. Twenty-First Century Socialism

- Conclusion

- Latin America & Twenty-First Century Socialism: Inventing to Avoid Mistakes

- Hugo Chávez on the Failed Coup

- Report from Venezuela: Aluminum Workers Choose Their Managers and Increase Production

- After the Referendum: Venezuela Faces New Challenges