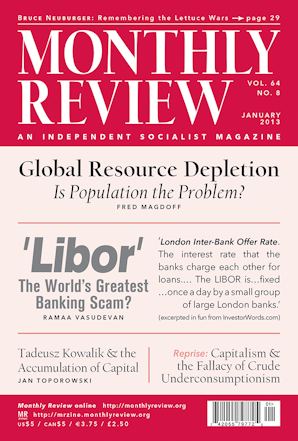

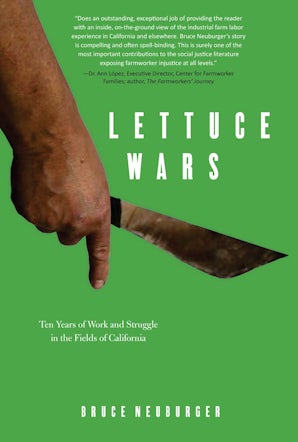

Also in this issue

- 'Libor'ing Under the Market Illusion

- Global Resource Depletion: Is Population the Problem?

- Tadeusz Kowalik and the Accumulation of Capital

- Repressing Social Movements

- Capitalism and the Fallacy of Crude Underconsumptionism

- Whiteness as a Managerial System: Race and the Control of U.S. Labor

- The Psychology of Culture: Making Oppression Appear Normal