Books by Ellen Meiksins Wood

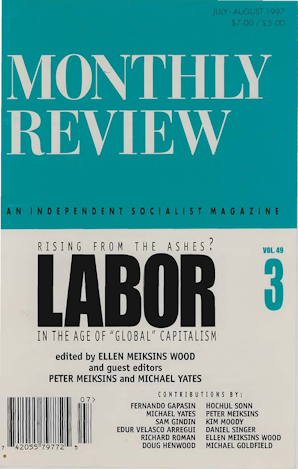

Rising from the Ashes?

Edited by Ellen Meiksins Wood, Peter Meiksins and Michael D. Yates

Capitalism and the Information Age

Edited by Robert D. McChesney, Ellen Meiksins Wood and John Bellamy Foster

In Defense of History

Edited by Ellen Meiksins Wood and John Bellamy Foster

Article by Ellen Meiksins Wood

- The Necessity of a Universal Project

- The Politics of Capitalism

- Unhappy Families: Global Capitalism in a World of Nation-States

- Kosovo and the New Imperialism

- Capitalist Change and Generational Shifts

- The Agrarian Origins of Capitalism

- The Communist Manifesto After 150 Years

- A Note on Du Boff and Herman

- A Critique of Tabb on Globalization