Also in this issue

- Repairing the Soil Carbon Rift: Enhancing Agriculture and Environment

- Building Communities of Solidarity

- History comes in bad cycles

- I wake to the possible

- What Sort of Kinetic Materialism Did Marx Find in Epicurus?

- Engels's Ecologically Indispensable if Incomplete Dialectics of Nature

- Socialist Practice and Transition

- Was Folk Music a Commie Plot?

Books by Michael D. Yates

The Political Writings of Bhagat Singh

Edited by Chaman Lal and Michael D. Yates

Work Work Work

by Michael D. Yates

Why Unions Matter

by Michael D. Yates

Can the Working Class Change the World?

by Michael D. Yates

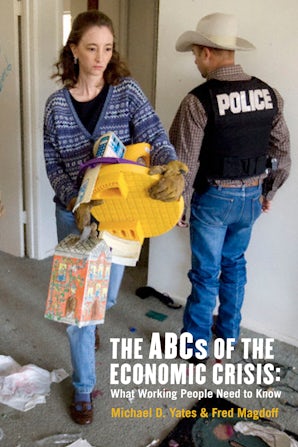

The ABCs of the Economic Crisis

by Fred Magdoff and Michael D. Yates

Article by Michael D. Yates

- 'Ballad of an American': The Illustrious Life of Paul Robeson, Newly Illustrated

- Panopticon

- COVID-19, Economic Depression, and the Black Lives Matter Protests: Will the Triple Crisis Bring a Working-Class Revolt in the United States?

- It's Still Slavery by Another Name

- Nothing to Lose but Their Chains

- Thinking Clearly about the White Working Class

- 'Mourning and Militancy'

- Measuring Global Inequality

- On Henry Giroux: Foreword to 'America's Addiction to Terrorism'