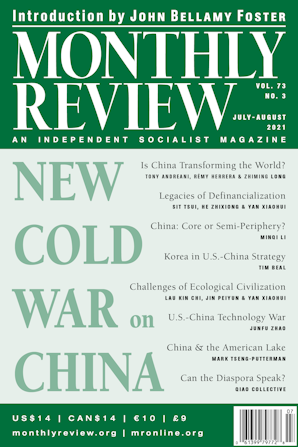

Also in this issue

- The New Cold War on China

- Is China Transforming the World?

- Legacies of Definancialization and Defending Real Economy in China

- China: Imperialism or Semi-Periphery?

- In Line of Fire: The Korean Peninsula in U.S.-China Strategy

- The Political Economy of the U.S.-China Technology War

- Can the Chinese Diaspora Speak?

- From Sandstorm and Smog to Sustainability and Justice: China's Challenges