Also in this issue

Books by Leo Panitch

Beyond Digital Capitalism: New Ways of Living

Edited by Leo Panitch and Greg Albo

Beyond Market Dystopia: New Ways of Living

Edited by Greg Albo and Leo Panitch

Transforming Classes

by Leo Panitch and Greg Albo

Rethinking Revolution

by Leo Panitch and Greg Albo

Edited by Leo Panitch and Greg Albo

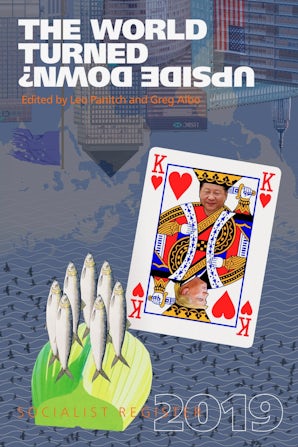

The World Turned Upside Down?

Edited by Greg Albo and Leo Panitch

Article by Leo Panitch

- Social Justice and Globalization: Are they Compatible?

- Violence as a Tool of Order and Change: The War on Terrorism and the Antiglobalization Movement

- Anti-Capitalism and the Terrain of Social Justice

- Renewing Socialism

- Rejoinder to Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin; Panitch and Gindin Reply

- The State in a Changing World: Social-Democratizing Global Capitalism?