From Solidarity to Sellout reviewed on Systemic Disorder

Mirror images and ideological straitjackets on the path from Solidarity to sellout

Apr 17

by Systemic Disorder

For much of the 20th century, there was a curious mirror effect between orthodox Soviet and Chicago School ideologies — both saw the other as the only other possible economic system. Although both time and the ongoing global crisis of capitalism has begun to chip away at such a ridiculous binary, to a maddening degree this ideological straitjacket continues to assert itself. A straitjacket that does not spontaneously materialize but is crafted for the maintenance of power.

The effects of this mirrored duality are still very much with us, and are a crucial factor in the path the countries of the former Soviet bloc have traveled. The usages of this ideological construct are obvious enough in the capitalist world, distilled into “there is no alternative” by the just departed Margaret Thatcher. Less obvious were the usages further East; perhaps the nearest equivalent of the prime minister’s “TINA” is Leonid Brezhnev’s declaration of the Soviet system as “irreversible.”

When the general secretary’s formulation began unraveling in the late 1980s, what was a Soviet bloc economist to do? For many, the answer was to pick up a copy of a book by Friedrich Hayek or Milton Friedman, and jump through the looking glass. And when their new mirror seductively told them to apply shock treatment to their own countries, they did — the mirror told them there was no alternative.

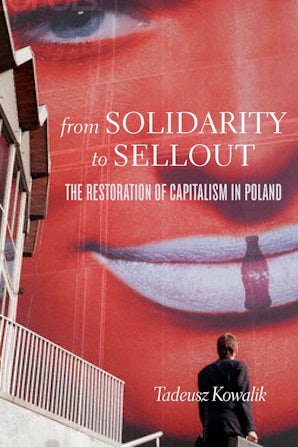

There is always an alternative, Polish economist Tadeusz Kowalik reminds us in his book From Solidarity to Sellout: The Restoration of Capitalism in Poland.* Professor Kowalik, drawing on his decades of experience as a reform socialist often on the outs with the communist authorities for his willingness to challenge orthodoxy, his work as an adviser with the Solidarity trade union and his personal knowledge of the key players, reminds us that Poland — and, by implication, the Soviet bloc as a whole — had an opportunity to create a different economy, one built on cooperatives and democratic participation in the economy.

Such an outcome was widely desired by Poles, and the outlines of such a system emerged in the “Round Table” negotiations held between Poland’s communist authorities and representatives of opposition groups, led by Solidarity, from February to April 1989. Economic democracy was already an established concept, embodied in the “Self-Governing Republic” program of Solidarity, adopted at its first national congress in 1981. In it, Solidarity, which consciously identified itself as a labor union and a broad social movement, declared:

“In the organization of the economy, the basic unit will be a collectively managed social enterprise, represented by a workers’ council and led by a director who shall be appointed with the council’s help and subject to recall by the council. The social enterprise shall … [work] in the interests of society and the enterprise itself. … The reform must socialize planning so that the central plan reflects the aspirations of society and is freely accepted by it. Public debates are therefore indispensable. It should be possible to bring forward plans of every kind, including those drafted by social or civil organizations. Access to comprehensive economic information is therefore absolutely essential.”

…

Read the entire review on Systemic Disorder