In Walt We Trust: How a Queer Socialist Poet Can Save America from Itself in Kirkus Reviews

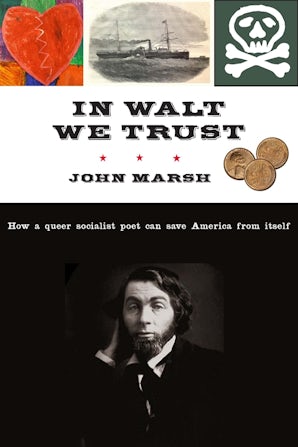

In Walt We Trust: How a Queer Socialist Poet Can Save America from Itself by John Marsh is forthcoming from MR Press in February 2015. The following will appear in the December 1 issue of Kirkus Reviews:

Marsh (English/Pennsylvania State Univ.; Hog Butchers, Beggars, and Busboys: Poverty, Labor, and the Making of Modern American Poetry, 2011, etc.) shares his affection for Walt Whitman in this gentle, thoughtful consideration of the poet’s relevance to 21st-century America. Beset by moral malaise in his 30s, the author “suffered from fully-grown doubts, not just growing doubts, about the meaning of life and the purpose of our country.” Whitman’s insights on death, money, sex and democracy buoyed his spirits. About death, for example, Whitman taught the atheist Marsh that dying was part of “the plan of the universe,” liberating the physical body to take new forms. Whitman wrote bitingly about what he called “The Morbid Appetite for Money.” Lusting after wealth, he believed, harmed the soul, inevitably leading to “lying, subterfuge, pettiness, and greed,” severing a “connection to the earth and to the people on the earth.” He promoted ideals of fairness and shared interest, which should characterize a just society, but Marsh does not go so far as to call him “technically or politically a socialist.” Celebrating the body, Whitman waged “an intense, inspired war against shame,” contradicting prevalent mid-19th-century views about modesty and sexual desire. Yet Whitman warned against shamelessness or narcissism; concern with one’s own pleasure should not lead to turning “others’ bodies to our uses.” Marsh cannot answer the question of Whitman’s possible homosexuality, but he does believe he was queer, “if by queer we mean differing from what is usual or ordinary, especially but not only when it comes to sexuality.” Whitman wrote with disdain about a democracy of ill-informed voters and self-serving special interests, but he believed in America’s potential to head “toward affection, toward friendship, toward a nation founded on care.” Marsh confesses his love for the legendary poet, and by the end of this insightful homage, readers are likely to feel the same.