Sure to “inspire new directions in research and debate” (“Dissenting POWs” reviewed in H-Soz-Kult, H-NET)

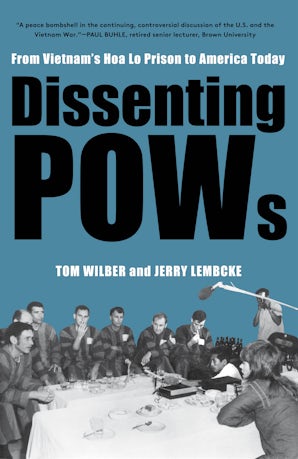

Dissenting POWs:

From Vietnam`s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today

by Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke

160 pages, $19 paper, 978-1-58367-908-1

Reviewed by Paul Benedikt Glatz, for H-Soz-Kult

Dissenting POWs rediscovers the story of American servicemen who came to critically view their nation’s war while imprisoned in North Vietnam. The book challenges widely held ideas of the POW (prisoner of war) experience as one of heroic resisters against enemy exploitation and torture, a key narrative of postwar revisionism and a popular trope in memory culture. Instead, there were diverse perspectives among captured U.S. servicemen, including opposition against their nation’s war and solidarity with the Vietnamese struggle for independence. Jerry Lembcke, author of several books deconstructing Vietnam myths, and Tom Wilber, son of an American POW, draw on archival sources and a critical re-reading of published material as well as new oral history accounts from the United States and Vietnam. Their book complements previous studies on the POW and MIA (missing in action) issues and their mythification and political impact with the little-known perspective of oppositional men among the captives.[1]

The recent controversy over the POW/MIA flag – the “most enduring symbol through which Americans came to remember the war in Vietnam” (p. 112) – evinces how the matter has been politicized and emotionally loaded, not least because of its critical role in military heritage as well as in postwar careers of such men as Senators John McCain and Jeremiah Denton.[2] Their stories contributed to the dominant narrative of “prisoners-at-war” (p. 23) who after capture continued their heroic fight by enduring torture. This ideal was established by high-ranking pilots shot-down early in the conflict. In North Vietnamese prisons they claimed authority over their fellow captives, demanded from them to bear physical violence, and to withstand offers of better conditions in return for antiwar statements. Their “hero-prisoner story” (p. 18) countered the images promoted by the North Vietnamese and their allies of captured airmen, helpless but nevertheless treated humanely. Reports by POWs of such fair conditions, in turn, were denounced as something between treason and opportunism. Without trivializing the hardships of often several years in jail, Wilber and Lembcke dissect personal accounts by former POWs. They point out contradictions, distinguish between physical punishment measures and deliberate violence, reconstruct different phases in the history of the prisons, and conclude that brutal treatment and torture were less common and systematic than purported.

Antiwar statements by POWs, the dominant narrative goes, had been pressed out of Americans by the North Vietnamese through torture and psychological manipulation….

Beyond their focus on the war and the postwar years, Lembcke and Wilber place the POW experience into a broader cultural historical context in order to understand the genesis and the persistence of the one-sided narrative. They find answers in the mindset of the Cold War era and the fear of communist infiltration and brainwashing. During the Korean War, any publicized statement by POWs was viewed with great skepticism. The archetype of the brainwashed POW, turned traitor or collaborator, would become the backdrop for the discrediting of dissident POWs in Vietnam. The authors argue furthermore that the expectations of U.S. servicemen going to Vietnam would considerably influence their latter memory of their war- and prison experiences. Their pre-Vietnam ideas of captivity and torture had been developed from popular cultural texts set in the Korean War. Several films of the time dealt with charges against returned POWs of collaboration with the enemy, often presented as the result of brainwashing and character weakness. Moreover, in pre-Vietnam films, Wilber and Lembcke observe racist depictions of the Asian enemies applying brutal and sadist torture methods against captured Westerners. On this basis, Wilber and Lembcke analyze U.S. POWs’ behaviour in Vietnam and their memory of their prison experience.

Beyond the Korean and Vietnam War eras, the authors find roots of the hero-prisoner story in captivity narratives of the colonial era. These involved a complex mix of violence against captives, their temptations to stay with their captors, the commitment to remain loyal with their fellow colonists, and their Christian beliefs. Such tensions and correlations between the Self and the Other were critical in the making of an American identity then, and, Wilber and Lembcke suggest, during the Vietnam War. Here, too, captured Americans must prove their will and ability to endure the brutality of a racialized Other, and autobiographical accounts echoed the traditional narratives when they presented torture as a “test of will and faith to be passed.” (p. 124) It is particularly intriguing to read about how the POW leaders themselves told of how they underwent self-mutilation, from fasting to self-inflicted physical injuries, in an effort of self-discipline and self-assurance, often with a religious subtext.

Dissenting POWs reintegrates the dissident prisoners of the Vietnam War into the larger American antiwar movement of oppositional servicepeople, veterans, and deserters. Beyond the selection of antiwar activists of the Vietnam- and later conflicts presented in the final sections of the book, who according to the authors carry on the “[h]eritage of [c]onscience” (p. 130) despite repression and revisionist discourse, I would have welcomed a more structurally oriented concluding analysis of the invaluable findings of Dissenting POWs and a discussion of the stimuli for debate and research it opens. A view beyond the United States and Vietnam, for instance, would have demonstrated the critical role of the POW issue, and arguably POW dissent, in the international Vietnam debates, East and West.[4] Notwithstanding, Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke have crafted an exemplary study of history and memory, offering answers from a wide range of sources and documents, and explaining the construction and persistence of narratives through biography, culture, politics, and national identities. Their remarkable book deconstructs not only widely held historical concepts of the Vietnam War but makes us alert of their repercussions in present-day culture and politics. Certainly, Dissenting POWs will inspire new directions in research and debate.

For the rest of the review, head to H-NET, Clio-online, H-Soz-Kult