1. Introduction

Defining moments in the history of a nation are time and again overshadowed by the drama of war. These critical events are often domestic policy decisions that affect the immediate state of a country and have serious consequences for the future. Significant examples in U.S. history include: the initial decision of the revolutionary government to found a republic dedicated to the lofty principles of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” but embracing slavery, a contradiction that ultimately led to civil war; the decision to prematurely end reconstruction efforts in the South after the Civil War, a policy reversal which allowed the long-term oppression and exploitation of the emancipated slaves and their descendents; and the decision during the Second World War to encourage the mass migration of poor African Americans from the rural South to the industrial centers of the Midwest and Northeast to support the war economy, a haphazard resettlement program that resulted in the ghettoization and continued oppression of a significant national minority.

The United States is currently at war and, simultaneously, at another historical crossroad of domestic policy that will not only undermine the economic life of working people, but will tax the social and political institutions of the nation at large. The stakes of the unfolding U.S. strategy to exploit millions of Mexican and Central American laborers as transient servants through a national guest worker program are staggering. Since a major component of the plan is to recruit or deport the unauthorized migrant population currently residing and working in the United States, a look at the target population suggests the scope of the strategy and its consequences.

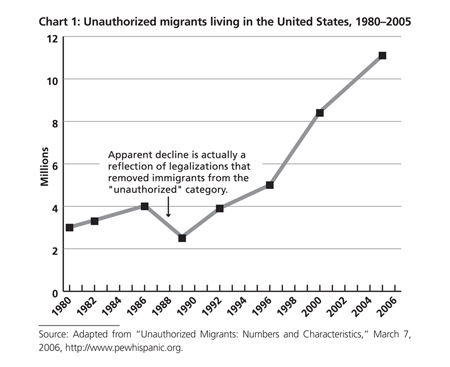

Chart 1 depicts the trend of unauthorized migrants living in the United States from 1980 through 2005.* The trend line in the chart records a steady growth in that sector of the population for the last twenty-five years. Since the mid-1990s, that population’s growth has been meteoric. It is important to note that the apparent decline during the late 1980s was actually produced by legalization measures that removed many immigrants from the unauthorized population count but did not decrease the actual number of immigrants in the country. Current estimates put the total unauthorized population living in the United States at 11.1–12 million people. These people are a primary target of the U.S. transient servitude program.

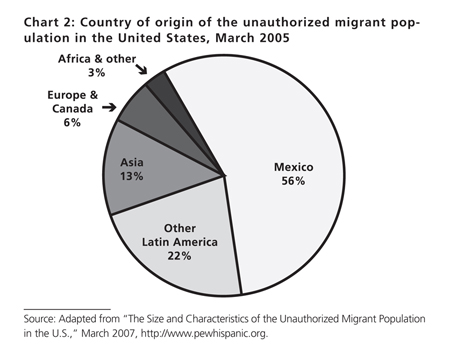

Chart 2 offers more essential information about this target population by identifying current unauthorized migrants in the U.S. by country of origin.

Chart 2 shows that, although unauthorized migrants from all over the world reside and work in the United States, almost 80 percent of the total are citizens of Mexico and other Latin American (primarily Central American) countries. This overwhelming majority status establishes that the primary target population for the transient servitude program will be the citizens of Mexico and Central American countries currently residing in the United States and suggests that most of new migrant workers who will be recruited through a national guest worker program will be from those regions.

A short history of the prior U.S. exploitation of the Mexican and Central American people is essential for understanding the implications of the latest program aimed at this target population.

2. A History of Exploitation

The United States has subjected the Mexican people to relentless exploitation since the inequitable war of 1846–48. Despite U.S. treaty obligations to respect the civil and property rights of Mexican citizens that resided in the territory seized during the war, efforts, both legal and illegal, to displace them from the land and reduce them to wage labor status began before hostilities ended. During the last half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, displaced and migrant Mexicans were employed extensively in mining, agriculture, and railroad construction in the West and Southwest.

The manpower demand produced by the First World War led to active recruitment by U.S. labor contractors in Mexico, not only to replace the rural U.S. workers who were drafted, but also for the booming manufacturing sector of the U.S. economy. The governments of both nations facilitated this mass migration of Mexican workers and cooperated in the establishment of a gatekeeper border policy that has continued to allow workers from Mexico to enter the United States when the economy is hot and restrict their passage during periods of economic recession.

The institutionalization of Mexican workers as a reserve labor pool for U.S. capitalism has produced waves of migration to the North, and, periodically, led to mass, and in some instances, forced, deportations. During the Great Depression, and later during the severe economic recession that followed the Korean War, large numbers of Mexican migrants were summarily deported to Mexico.

Despite periodic political backlashes against Mexicans in the United States, the demand for their labor has endured. Even the second forced deportation, Operation Wetback, which targeted Mexican communities across the nation, did not stop the use of Mexican workers as agricultural laborers through the infamous Bracero Program.

The Bracero Program

The history of the Bracero Program, an indentured servitude program which allowed for the temporary migration of Mexican agricultural workers to the United States from 1942 to 1964, is important because of its impact on the lives of millions of Mexican workers. In addition, it was the first bilateral agreement regulating migrant labor between the two nations. The Bracero Agreement offers the historical and legal precedent for the program currently being developed for the mass exploitation of Mexican and Central American workers in the United States.

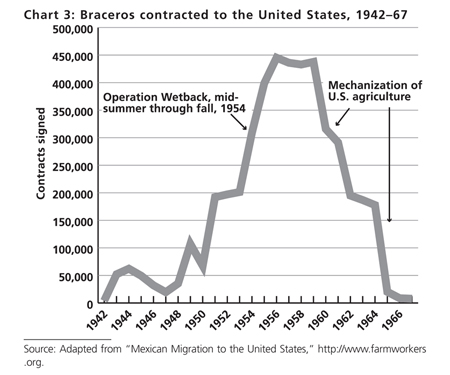

Chart 3 captures the dynamics of the Bracero Program. The time line in chart 3 tracks the official number of individual contracts that were signed with the U.S. government by Mexican workers during the period covered by the Bracero Agreement. It shows that the program, initially proposed to deal with the manpower shortage in the United States triggered by the Second World War, worked as it was intended—the number of bracero contracts signed rose rapidly during the war and then declined steadily in the immediate postwar period. The most significant feature of the time line, however, is that it reveals that the vast majority of the Mexican workers who signed bracero contracts were employed during the 1950s, indicating that U.S. capitalism was quick to take advantage of cheap Mexican labor and expanded the program far beyond its original mandate.

Chart 3 also documents the duplicity of U.S. policy toward Mexican migrants that was manifested quite clearly in the 1950s when an economic recession triggered a political backlash against Mexican migrants. Operation Wetback, as it was officially designated, was a paramilitary campaign conducted by the U.S. Border Patrol against Mexican communities across the nation that resulted in the deportation or flight of well over a million migrant workers and their families. Chart 3 shows clearly that the demand for indentured Mexican workers continued to rise despite Operation Wetback, reaching an annual average of 430,000 a year during the second half of the decade.

Chart 3 also records the decline of the Bracero Program. Although both opposition by organized labor and public outrage against the abuses of the program were factors in the termination of the agreement, the dramatic drop in demand for indentured Mexican labor corresponded to the overall decline in farm employment resulting from the extensive mechanization of U.S. agriculture during the 1960s (The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy, http://www.ers.usda.gov). In short, most of the backbreaking fieldwork that was being done by bracero labor simply disappeared. Although the official program of utilizing indentured workers was ended in 1964, the exploitation of Mexican migrants in the worst and lowest paying jobs in U.S. agriculture has continued to this day.

Ultimately, over 4.6 million Mexican citizens entered the United States under the Bracero Agreement, providing an abundant supply of cheap workers for U.S. agriculture as long as it was needed. Though the program provided desperately needed jobs to Mexican workers, the bracero experience was characterized by poverty wages, substandard working conditions, social discrimination, and lack of even the most basic social services for braceros and their families.

U.S. demand for Mexican workers did not disappear with the termination of the Bracero Program. The tradition of exploiting cheap Mexican labor, firmly established during the First World War, institutionalized through bilateral agreement during the Second World War, and expanded during the postwar era, continued with the establishment of the maquiladora manufacturing system in Mexico.

The Maquiladora System

U.S. capitalism invaded Mexico in pursuit of cheap labor the year after the termination of the Bracero Agreement. In 1965, Mexican president Diaz Ortiz signed into law the Border Industrialization Program (BIP) that established the maquiladora system in Mexico. Developed by U.S. business interests and secured through “dollar diplomacy,” the BIP granted U.S. industry access to Mexican labor, initially along the U.S.-Mexico border and later expanded under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) into the interior of Mexico, with virtually no liability for the social or environmental costs of production.

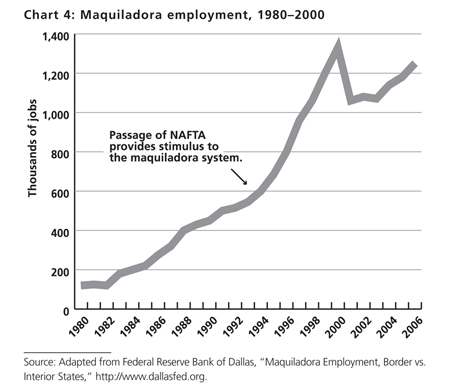

Chart 4 tracks the growth of the maquiladora manufacturing system in Mexico. The system built up slowly—in 1980, fifteen years into the program, slightly more than 500 maquilas employed about 120,000 workers. In the following fifteen years, maquiladora employment increased five-fold to over 600,000. Employment soared in the late 1990s, peaking in the year 2000 with approximately 1.3 million workers employed in over 3,000 plants. The program showed an abrupt decline accompanying the mild economic recession in the United States in 2001 but is currently in a period of strong recovery. Overall, the maquiladora system has been a boon to U.S. capitalism, keeping the costs of production down and profits up in many critical U.S. industries.

The costs of the maquiladora system have fallen on Mexico. Maquila industries have produced a sizable number of jobs, but real wages have declined throughout the history of the program. In addition, Mexico has lost untold revenues and resources, and, therefore, opportunity for national development. The social and environmental costs of the maquiladora system in Mexico have been well documented and continue, exacerbated, under NAFTA.

Especially relevant to the unfolding U.S. labor strategy is the fact that the maquiladora program resulted in substantial resettlement of the working-age Mexican population along the U.S.-Mexico border that was supplemented in the 1990s by many of the over one million Mexican farmers dislocated by NAFTA. High unemployment in Mexican border cities, despite the thriving maquiladora industry, and higher wages to be earned in the booming U.S. economy triggered the flood of immigrant laborers that entered the United States during the 1990s and early 2000s. The exodus was facilitated by the lax enforcement of immigration law in the United States and an unofficial open border policy.

A Gatekeeper Border Policy

Though a gatekeeper policy dictated by the needs of the U.S. economy for Mexican labor has been in effect since the U.S. conquest of Mexico, the resettlement of unauthorized migrants to the North since 1990 is unprecedented and has been facilitated by a virtually open border policy.

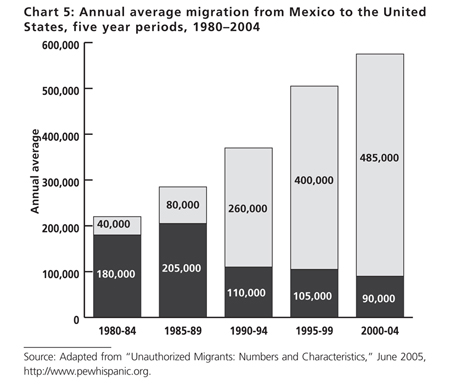

Chart 5 highlights the significant trends of contemporary migration from Mexico. It compares legal versus unauthorized migration from Mexico to the United States for chronological five-year periods from 1980 through 2004. The numbers on the bars represent annual average migration during each five-year period. The overall trend shows a steady increase of migration for the last twenty-five years. The most significant trend, however, is the constantly increasing predominance of unauthorized versus legal migration during the last fifteen years. While unauthorized migration accounted for less than 25 percent of all Mexicans relocating to the United States during the 1980s, it has risen to a staggering 84 percent of the most recent Mexican migrants. These findings indicate that, because of the rising demand for cheap Mexican and Central American labor during the last fifteen years, a gatekeeper border policy has kept the southern U.S. border virtually wide open so as not to impede the migration.

Chart 5 suggests that the much-touted Border Patrol operations against unauthorized migrants of the mid-1990s, Hold the Line (San Diego, 1993) and Operation Gatekeeper (El Paso, 1994), were either the worst failures in that agency’s history, or official grandstanding to cover an unofficial open border policy demanded by American capitalism. The U.S. history of drawing on Mexican labor during economic booms and the current dependency of the U.S. economy on cheap labor from south of the border indicate the latter.

This short history of the exploitation of Mexican labor as a reserve labor pool for U.S. capitalism provides background for the current strategy systematically to exploit Latin American workers as transient servants inside the United States under a national guest worker program. This latest plan, which targets millions of workers from the South, is more sophisticated and grander in scale than anything that has gone before. Consequently, it is requiring unprecedented international and domestic preparations.

3. Setting the International Stage

The scope and scale of the unfolding U.S. labor strategy has necessitated international preparations. Two key prerequisites for the realization of the plan are, first, a plentiful supply of workers who will toil for substandard wages under adverse working and social conditions, and, second, the establishment of international law that sanctions free trade in human labor across national boundaries. The pauperization of the Mexican and Central American working classes and initiatives in the World Trade Organization (WTO) to create global guest worker guidelines have set the stage for initiating a strategy of transient servitude in the United States.

The Pauperization of the Mexican and Central American Working Classes

U.S. financial and political intervention in the national life of Mexico during the 1980s and 1990s, often carried out through the WTO, has pauperized the Mexican working class. It is they who have had to suffer the brunt of the mandatory austerity programs, strict debt restructuring, and privatization initiatives that were imposed on Mexico in the 1980s after the credit binge of the Mexican bourgeoisie during the previous decade. The result of this foreign intervention has been widespread unemployment and displacement from the land that has produced onerous hardship and sparked internal migration from the interior of Mexico to the industrialized border region and to the United States. It is widely acknowledged that NAFTA has exacerbated all of the problems created by the financial and political interventions of the 1980s and that the purpose of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) is to expand the U.S. sphere of influence, including access to cheap labor, into Central America.

Although U.S. capitalism has profited handsomely from the pauperization and northward migration of the Mexican working class through the BIP and an open border policy that has provided a steady supply of cheap labor to sustain the U.S. economy for the last fifteen years, the pending U.S. strategy to implement a comprehensive transient servitude program will intensify the exploitation of Mexican and Central American workers. The plan will be advanced significantly if it is sanctioned under global guest worker guidelines being developed in the WTO.

GATS: Establishing Global Guest Worker Guidelines

Free trade in workers across international borders is a primary goal of global capitalism. While offshoring schemes, such as the Border Industrialization Program, transfer the work of manufacturing industries to regions with cheap labor, the goal of global guest worker programs is to import cheap labor for agriculture, site-bound manufacturing, and local service industries. To facilitate the global movement of workers the developed nations of the world have joined forces to legitimize this latest form of free trade through international law and thereby sanction the practice of transient servitude in the modern world.

The WTO’s existing General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) categorizes international service industries into four “modes” depending on the location of the provider and the consumer at the time the service is rendered. Mode 4 applies specifically to the “temporary movement of natural persons [workers as opposed to corporate entities] across borders to provide services.” The key stipulation of Mode 4 is that migrant workers must either be employed by a foreign firm with commercial presence where the service is provided or be under contract for the provision of a service.

This employment/contract captivity stipulation of Mode 4 establishes the servitude status of modern migrant workers. The migrants’ visas are employer or contract bound, so they must remain employed to maintain their legal status. Linking the legal status of the worker to a binding contract shifts virtually all the power to the side of the employer or contractor and inevitably leads to abuse—a fact that the twenty-two year history of the Bracero Agreement and all other guest worker programs demonstrate unequivocally. The WTO is well aware of the potential for abuse under Mode 4 and openly disavows any responsibility for the rights of migrant workers.

Although most existing guest worker programs are based on bilateral agreements, current negotiations to extend Mode 4 to all workers will in effect establish a global guest worker program that will supersede all existing agreements. Extending Mode 4 will have grave implications for tens of millions of migrant workers and their nations of origin: The outcome of current Mode 4 negotiations will constitute a set of rules and regulations that participant nations will have to take as a whole and will not be able to amend.

Commitments to the program will be legally binding for at least three years on participant nations that, after the initial period, will only be able to withdraw by paying compensation to all WTO members. The penalties for withdrawing will amount to billions, if not trillions, of dollars, compelling poor countries to supply cheap labor as long as rich nations demand it.

Foreign governments will be able to challenge any national labor regulations. WTO tribunals that supersede all national judiciaries and are not subject to public scrutiny would resolve all conflicts.

This extended GATS Mode 4 is the model behind the U.S. strategy to exploit Mexican and Central American labor that is currently unfolding.

4. The U.S. Strategy Unfolds

Because the idea of human servitude runs counter to the political sentiments of many Americans and is bound to generate opposition, the current U.S. strategy of mass transient servitude remains undeclared even as it unfolds. However, like the provisions on the international level, extensive domestic preparations are currently underway to facilitate the influx of millions of migrants from Mexico and Central America into the United States. These measures include: the building of transportation and enforcement infrastructures to facilitate the movement and management of millions of migrants; the promotion of immigration legislation to legitimize transient servitude in the United States; and initial steps to implement the program in full as soon as it becomes the law of the land.

Building the Transportation Infrastructure

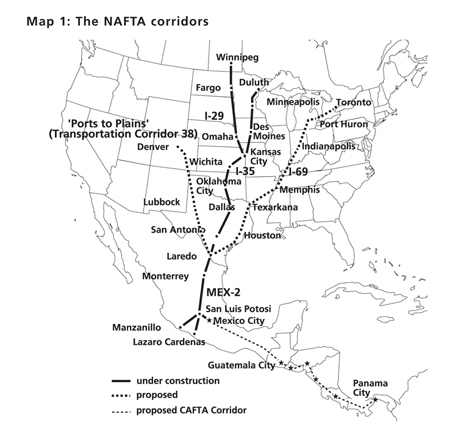

Map 1 depicts the transportation infrastructure that is being developed to accommodate the increasing traffic in goods and labor between the United States and Latin America. The NAFTA corridors designated on the map, which currently consist of existing Mexican Federal Highways and specific sections of the U.S. Interstate Highway System, are being expanded through what is being touted as the biggest surface transportation project in history. When construction is completed, the largest sections of the I-35 corridor, located in Texas where the traffic is heaviest, will be up to 1,200 feet wide and include four truck lanes, six auto lanes, six passenger and freight rail lines, necessary safety medians, and wide service and utility zones (for a complete discussion of the scope and impact of the NAFTA corridor system see: Richard D. Vogel, “The NAFTA Corridors: Offshoring U.S. Transportation Jobs to Mexico,” Monthly Review, February 2006).

The NAFTA corridors will be integrated transportation super-corridors to consolidate the existing streams of NAFTA trade goods, containerized freight from the Far Eastern Pacific Rim routed through Mexico, current migrant traffic, and accommodate the additional human traffic generated by a national guest worker program. The combined traffic, already heavy on existing I-35, will increase exponentially when the new I-35 corridor, already under construction, is completed. The proposed I-69 corridor is intended to carry the traffic from Mexico bound to eastern and northeastern U.S. destinations. The stated purpose of the future “Ports-to-Plains” corridor from Laredo to Denver (which has not yet been numbered) is to exploit cheap goods and labor from Mexico to develop the sparsely populated plains of west Texas, northeastern New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado.

I-35, which already carries a trickle of farm workers from the Mexican states of Tlaxcala, Guanajuanto, Mexico, and Hildago to the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec under an existing bilateral guest worker agreement, is slated to become the main conduit of the U.S. guest worker program, transporting an unending stream of transient labor between the heart of Mexico and the heartland of America. Both San Antonio and Kansas City have been designated as inland Ports of Entry, a unique status that will allow them to be utilized as guest worker processing centers.

Like the massive transportation network under construction, an expanded migrant control infrastructure is being developed to enforce a national guest worker program as soon as it is implemented.

Expanding the Enforcement Infrastructure

The expansion of Detention and Removal Operation (DRO) facilities operated by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the other major area of infrastructure development to facilitate the mass influx of migrant workers from the South. Monitoring and enforcing a national guest worker program in the United States that will ultimately involve tens of millions of migrant workers from Mexico and Central America is the biggest human management program that has ever been undertaken. Expansion of the facilities that will be needed to detain and remove unauthorized migrant workers from the United States is already underway.

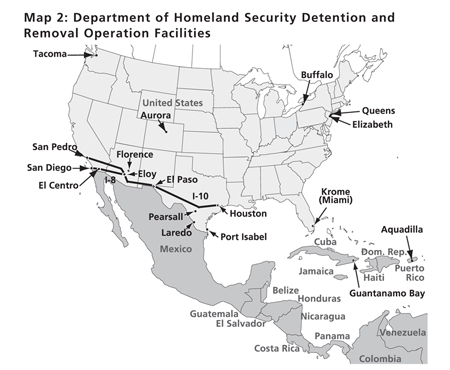

Map 2 identifies the locations of the current DRO facilities in the United States, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The map reveals that eleven of the existing eighteen DRO facilities are strategically located to regulate the flow of migrants across the southern U.S. border. The largest of these facilities (which opened in May 2005) near Pearsall, Texas and the Laredo detention facility are both located on the I-35 corridor. The Houston, El Paso, Florence, Eloy, and San Pedro facilities are all located along I-10, the main east-west highway that parallels the U.S.-Mexico border. The San Diego and El Centro facilities, linked to I-10 by I-8, complete the southern border enforcement infrastructure. The proximity of the Guantánamo Bay facility to both Central and South America suggests that the current construction at that site foreshadows detention and removal operations for those regions. Aquadilla and Krome, DRO facilities currently serving the Caribbean, are in excellent positions to process guest workers from that region.

As much as map 2 reveals about how DRO facilities will be used to facilitate a guest worker program, it does not present the complete picture. In January 2006, the DHS awarded a $385 million contingency contract to KBR, the engineering and construction subsidiary of the Halliburton Company, to establish temporary DRO facilities to supplement the existing ones in the case of an “immigration emergency.” Questions about the nature of the anticipated “immigration emergency” not answered by the expansion of the transportation and enforcement infrastructures depicted in maps 1 and 2 are answered by examining the major immigration legislation that was introduced in Congress in 2006 and the concrete steps that have already been taken to implement a national guest worker program.

Immigration Reform: Legitimizing Transient Servitude

While the WTO can supply international guidelines and sanctions for guest worker programs, a national program of transient servitude must be drafted and sanctioned by U.S. law before it can be implemented. Table 1 presents a summary of the major immigration legislation that was introduced in Congress in 2006.

Table 1 erases any doubts about U.S. intentions to legalize the wholesale exploitation of Mexican and Latin American workers through a national guest worker program. The table reveals that Representative Shirley Jackson-Lee offered the only major immigration reform proposal introduced in the 109th Congress that did not embrace a guest worker program.

Common threads run through all of the guest worker proposals:

- All of the guest worker programs link visas to employment. Portable visas allow workers to change jobs and remain in the program.

- None of the guest worker programs are sector specific, meaning that all industries in the United States will be entitled to exploit cheap migrant labor.

- All of the guest worker proposals double the fines for employers who hire undocumented migrant workers, insuring maximum employer participation in the program.

- All of the proposals insure the transient nature of the program by restricting the maximum length of worker participation to no more than six years.

- None of the current guest worker proposals guarantee a clear path to legal residency. Legal residency is conditional under three of the proposed programs (with employer sponsorship in two of those) and not even offered by the other two.

- All of the pending guest worker programs call for increased southern border enforcement with massive expansion of DRO facilities. The fact that only H.R.3333 calls for the open militarization of the border is a moot point since the southern U.S. border is already being militarized by the DHS under the Secure Border Initiative (SBI).

- With the exception of S.1033, all of the proposals either require or reward local and state participation in immigration law enforcement.

Overall, Alan Specter’s (the chairman’s mark) proposals, including the provision to expand expedited removal to the entire southern border, are committee recommendations that will probably prevail in the final form of the national guest worker program.

Adoption of the U.S. guest worker program as the law of the land and securing bilateral agreements with Mexico and the Central American countries through NAFTA and CAFTA according to the GATS Mode 4 guidelines will legitimize and therefore facilitate the strategy that is already being implemented though current government initiatives.

Implementing the Program

The U.S. strategy to capture and exploit Mexican and Central American labor through a national guest worker program, while awaiting a rubber stamp from Congress, is already well underway. In addition to the transportation and infrastructure projects reported above, comprehensive government policies to implement the program have already been formulated and initiated. These specific policies include: sealing the U.S. southern border as tightly as possible in order to stop unauthorized migration; provisions for the mass detention and removal of unauthorized migrant workers presently residing and working in the United States; and the reorganization and mobilization of government agencies to enforce the provisions of the guest worker program as soon as it becomes law.

Secure Border Initiative: Sealing the Southern Border

Although the goal of supporting a national guest worker program is the last item in the Secure Border Initiative Fact Sheet posted on the DHS web site (http://www.dhs.gov/), the geographical location of existing DRO facilities indicates that it is going to be the primary function. DHS has assigned the job of sealing the southern U.S. border to the Office of Border Patrol under U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The current CBP commissioner proclaims that the new National Border Patrol Strategy “embraces and builds upon many elements of Operations Gatekeeper and Hold the Line; however, it goes beyond the deterrence strategy embodied in those operations and it is more than a strategy just for the southwest border.” It “has an ambitious goal: the operational control of our nation’s border, and particularly our borders with Mexico and Canada.”† To this end, the commissioner pledges the deployment of more highly trained and well-equipped Border Patrol agents, integrated detection and sensor technology, including unmanned aerial vehicles, and strategically placed tactical infrastructure.

Although Objective 1 cited in the National Strategy is stated as “the apprehending of terrorists and their weapons as they attempt to illegally enter the United States between points of entry,” the actual allocation of manpower and material resources by the Border Patrol indicates that Objective 2—to “Deter illegal entries through improved enforcement”—is the highest priority of the agency. This sealing of the southern border is the first step in implementing the guest worker program aimed at capturing and controlling Mexican and Central American workers in the United States.

ICE, the DHS agency that has been tasked with the mass detention and removal of undocumented migrants already living and working across the United States, is the largest special weapons and tactics (SWAT) unit that has ever been mobilized, and Endgame is the agency’s strategic plan that will initiate the program of transient servitude across the nation. Endgame will be the biggest police action in history.

5. Endgame: The Plan for the Mass Deportation of Undocumented Migrants

Endgame is the DHS strategic plan to remove all unauthorized migrants in the United States within ten years.‡ The plan, instituted in 2003 and scheduled for completion by 2012, in conjunction with the ongoing legislative initiative for a national guest worker program, clearly establishes the time line of the unfolding U.S. strategy to exploit Latin American labor.

Endgame is basically an expanded replay of Operation Wetback. The goal of the two operations is the same: the mass removal of undocumented Latin American migrants from the nation at large while continuing to exploit the labor of those who remain under captive contract. The scope of Endgame, however, eclipses the short-term deportation project of 1954: “The DRO strategic plan sets in motion a cohesive enforcement program with a ten-year time horizon that will build the capacity to ‘remove all removable aliens,’ eliminate the backlog of unexecuted final order removal cases, and realize its vision.”

The final campaign of Endgame, a nationwide assault on the established communities of undocumented migrants living and working in the United States and the deportation of millions of men, women, and children to Mexico and Central America, is the “immigration emergency” anticipated by the DHS. It will be the biggest mass deportation in world history. To “remove all removable aliens” means to locate, arrest, detain, and deport in excess of twelve million people. The logistical problems alone are staggering and, if ICE meets organized resistance, the operation could indeed produce an “immigration emergency.” People with their lives invested in the United States and with nothing to return to in their home countries might not go without a fight. The organization and training of ICE for military operations indicates that DHS is anticipating just such a contingency.

The ultimate DRO vision is highlighted in Endgame: “Within ten years, the Detention and Removal Program will be able to meet all of our commitments to and mandates from the President, Congress, and the American people.”

The forthcoming mandate from Congress, clearly foreshadowed in the immigration reform legislation introduced in 2006, is beyond doubt: the establishment of a U.S. guest worker program under the aegis of GATS that will reduce Mexican and Central American workers to a condition of transient servitude. It will be a program that serves the interest of U.S. capitalism at the cost of the developing nations to the South. Though it will offer menial jobs to many Latin American workers, it is nothing more than the latest stage in the history of the U.S. exploitation of the South. If it becomes public law, it will be enforced by the most powerful state in history.

DHS: Enforcing Transient Servitude

The pending U.S. guest worker program to exploit Mexican and Central American labor will be administered and enforced by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the most powerful and pervasive agency of state control that has ever been mobilized. To monitor and control the movement of migrants, DHS can employ unprecedented police power: U.S. Customs and Border Protection; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; the U.S. Coast Guard; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; the Transportation Security Administration; and the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center to train and enlist state, local, and international police agencies for immigration law enforcement.

Indeed, if a national guest worker program becomes the law of the land, chances for migrant Latin American workers in the United States to avoid being trapped in the program of transient servitude will be nil.

6. Transient Servitude: A Close-Up

The innocuous term, “guest worker,” obscures the true nature of transient servitude. The term “guest” suggests a person to whom hospitality is extended, but this labor program will offer no kindness or generosity to workers caught in the trap. The program will be conducted primarily by private corporations (perhaps exclusively by Halliburton/KBR or one of its subsidiaries) that are only interested in the bottom line of profits for their stockholders and huge salaries and bonuses for their managers and executives, and it will be enforced by the unprecedented power of the U.S. government and guaranteed by the WTO through GATS.

The work offered under the program will be transient in a double sense—the work visas will be temporary and employment will be itinerant because of visa portability. Limited to a maximum of six years of participation and with the prospect of legalization conditional, the program offers workers an uncertain future at best.

A condition of servitude is all but guaranteed during the term of employment because GATS has officially disavowed any responsibility for enforcing international labor law advocated by the International Labor Organization (ILO), which itself has no enforcement provisions. Ironically, workers under the pending U.S. guest worker programs will have less protection than the workers who labored under the Bracero Agreement because of the power of GATS to supercede all national (including labor) law thus nullifying worker rights guaranteed in the Mexican Constitution.

The exploitation of workers under the U.S. guest worker program will, in practice, be virtually unrestricted and participation will be expensive. In addition to the visa and work permit fees required by the U.S. government, workers will have to absorb the commission fees charged by labor contractors and transportation costs (both prohibited under the Bracero Program), and additional charges for medical exams, inoculations, and miscellaneous expenses. In practice, the costs born by migrant laborers under a U.S. guest worker program will greatly reduce the money available for remittances to families in Latin America, one of the primary motivating factors for participating in the program.

In the end, all that guest workers will get are short careers of transient servitude in the United States without the guarantee of minimal labor standards or any social security, and during which a large proportion of their earnings will be siphoned away by U.S. labor contractors and opportunistic goods and services providers.

The dead-end prospects for millions of Latin American “guest workers” in the United States are a foregone conclusion. What remains to be considered is the impact that the program will have on native workers and the nation at large.

7. Servitude—Past and Future

The history of the United States holds powerful lessons about the economic, social, and political costs of human servitude. The practice of slavery backed by the power of the state during the first eighty years of the republic devalued the labor of all working people and finally resulted in a civil war that almost destroyed the nation. And while the pending program of transient servitude will not be as oppressive as chattel slavery, it will produce the same erosive economic effect—the presence of millions of workers toiling at substandard wages in all sectors of the U.S. economy will undercut the value of the labor of all working people in the nation, and, considering the scope and size of the pending guest worker program, the aggregate effect will be far greater than the cost of slavery in the past. With the expensive infrastructure in place and the program sanctioned by the WTO, legitimized by U.S. immigration law, and enforced by the DHS, state, and local police, transient servitude will become so entrenched in the U.S. economy that it might well prove to be nearly as difficult to abolish as the practice of chattel slavery was.

The prospective social impact of a national guest worker program is not without precedent. Again, while the social discrimination accompanying transient servitude may not prove to be as harsh as life in the bracero work camps of the U.S. Southwest, or the postwar African-American ghettos, the scope of the social impact will be far wider, penetrating every community in the United States. The acute regional social problems created by servitude and oppression in the past will become chronic national problems under a guest worker program.

The political problems generated by a national guest worker program will be daunting. Since the pending program will target mainly young, uneducated, and unskilled workers—the most volatile sector of any population—and displace many corresponding native workers, the problems of social control will be manifold and trigger further expansion of the already burgeoning police functions of the state. A new surge of mass incarceration, which might surpass the record numbers that accompanied the deindustrialization of the U.S. economy in the 1980s and 1990s, can be expected (See Richard D. Vogel, “Capitalism and Incarceration Revisited,” Monthly Review, September 2003).

Not the least of the political considerations is the fact that the initiative to adopt a national guest worker program is the latest battle in the campaign against organized labor that was launched in the 1980s. While the offshoring of manufacturing jobs and the flood of anti-union legislation have devastated traditional unions, the prospect of having millions of workers trapped in transient servitude in the United States threatens to nullify current labor movements throughout the Americas.

Despite the clamor in Congress from both conservatives and liberals for a national guest worker program, it is a reactionary policy with dire economic, social, and political ramifications. The working people of the United States must respond to the pending program of transient servitude with the same answer we have given to all forms of human servitude in the past—a resounding NO!

We are facing the fight of our lives.

Notes

- * This article draws heavily on demographic research developed and published by the Pew Hispanic Center (http://www.pewhispanic.org), which is widely recognized for its validity and is used to formulate U.S.immigration policy.

- † National Border Patrol Strategy,September 2004, http://www.cbp.gov/.

- ‡ ENDGAME: Office of Detention and Removal Strategic Plan,2003 –2012,Detention and Removal Strategy for a Secure Homeland, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Form M-592 (8/15/03)was originally posted on the Web site of the DHS but has been removed. It can still be found through an online search and is available from the author at irvogel [at] aim.com.

Comments are closed.