A few weeks ago, the New York Times columnist on economics devoted his space to scolding the demonstrators at the Summit of the Americas in Quebec City, (April 22, 2001, Op-Ed page). The writer, Paul Krugman an MIT professor, is considered by many to be a leading light of the profession, and a likely candidate for the economics Nobel Prize.

Himself something of a liberal, Krugman appreciates that the demonstrators have kind hearts. The problem, though, is that they are stupid. The “people outside the fence, whatever their intentions, are doing their best to make the poor even poorer.” The people in the poor countries will be poorer if they don’t get jobs in multinational subsidiaries. If the latter don’t hire child labor, the children will end up in even worse jobs or on the streets, many turning to prostitution. God bless the multinationals!

The professor gets down to business as he explains what sensible people should understand. “The point is that third world countries aren’t poor because their export workers earn low wages; it’s the other way around. Because the countries are poor, even what looks to us as bad jobs at bad wages are almost always much better than the alternatives.”

But what if the poverty of nations stems from a long history of imperialism—due to formal and informal colonialism, and the destruction of whole societies by the slave trade and other means? And what if the poor countries are kept in constant bondage by the multinational industrial and financial firms in partnership with the ruling classes of the poor countries?

It is generally understood that a crucial key to economic development rests on the reinvestment of the available economic surplus. Profits from agricultural, mining, and industry provide the means for economic growth. There is no guarantee that this surplus will be used for useful investments. The profit makers may use the surplus to build grandiose palaces, hire hordes of servants, or engage in war. The surplus may thus be wasted, harming the people. And if the surplus is diverted or if it is wasted, a poor country will remain poor. A major reason for the poverty of the poor countries, for the ever widening gap in wealth between poor and rich countries, is that surplus produced in the poor countries is being diverted to the rich countries.

The point to be noted is that these benevolent multinationals, the givers of jobs, the exploiters of the environment are at the same time extracting the surplus to fatten the wealth at home. Not only that, as long as the market rules, this surplus extraction contributes to a continuous bondage to the centers of capital

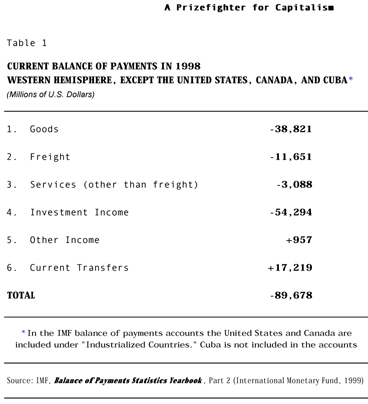

Please bear with us as we demonstrate our argument. Since the affair in Quebec was a Summit of the Americas, we are presenting data for all countries of the Western Hemisphere other than the United States, Canada, and Cuba (see table 1).

The balance of payments consists of 1. A current balance which summarizes (a) a country’s imports and exports, (b) the net income on investments, such as payments of profits and interest on debt, and (c) transfers between individuals (for example money sent home by nationals working abroad). 2. A capital balance of payments that records investments and loans, such as those made by multinationals and banks.

The numbers given are for the current balance of payments because these data go a long way toward explaining the bondage of poor countries associated with the dominance of the rich countries. (The capital balance of payments—the movements of long term capitals—are part of the same process and produce the same effect. But we don’t want to complicate the argument here with further batches of numbers.) So let us examine each of the five items that make up the current balance of payments of the whole Western Hemisphere other than the United States and Canada. The data are from the 1999 IMF annual on the subject. The numbers naturally vary from year to year, but the basic pattern remains the same.

The first line of the table shows an approximate deficit of $38 billion. In other words, imports exceeded exports by that much. The multinationals themselves account for a good part of imports and exports. In addition to being exporters they are also importers of machinery, equipment, raw materials, and components for the businesses they operate.

The second line shows that the net cost of moving freight to and from abroad (ships, railroads, and trucks) is paid—to foreign capital. The cost of “other services” (line 3) includes payments to foreign capital to insure freight movements

The fourth line—a crucial item—summarizes the net outflow of payments to foreign investors and lenders, such as: dividends and profits to foreign investors; and interest on debts owing to foreign banks, IMF, World Bank, and governments.

Only the last two lines are positive. A large reason for the positive balance shown in the last line is due to the inflow of money sent back to the family by members who have emigrated or temporarily work abroad.

All in all, the countries of Central America, South America, and the Caribbean were in a hole on the current balance of payments in 1998: they needed to settle a current debt of about $90 billion. This was not a one-year problem. Such an imbalance is chronic. Sometimes less, sometimes more.

So what? The United States has had an ongoing and sizeable deficit in its current balance of payments since the 1970s. However, there is a vital difference between that deficit and the Latin American one. In one case, it has aided in a growth of wealth. In the other it has shackled the economies. One reason for the difference is that the U.S. dollar is an international currency. So much so that large dollar hoards are kept by central banks as reserves against payments needed in case of reversals in trade and/or capital flows. The dollars resting in vaults or bank accounts of the rich central banks are sterile: they produce no income. To overcome the sterility, central banks buy U.S. Treasury bonds on which they get a little interest, but still income. This money flow from central bankers helps pay part of the U.S. balance-of-payment deficit. In addition, foreign capitalists see the United States as a safe haven for their surpluses. After all, who else has the military might to destroy the rest of the world? Further, this presumably safe haven offers lots of opportunities for making good money. In short, the U.S. deficits are covered by a net inflow of foreign funds. And if worse comes to worse, the United States can print more of its internationally accepted currency.

Now let us turn to the Latin American countries. They cannot pay off the deficit with pesos, reals, or sucres. These are not monies accepted in international monetary transactions. Those who have sold goods and services, lent money, or draw profits will not be satisfied unless they are paid in dollars, euros, and yen. Therefore, the deficit-ridden poor countries have to either borrow still more from foreign bankers or attract new capital investments from abroad. As a result, more money becomes due annually to foreign capital. In 1998, 60 percent of the deficit (line 4 divided by the total) was due to the net flow to foreign investors. The additional inflow of foreign capital will as a rule increase that part of the deficit—in short, it acts as a halter on the society. More and more of the economic surplus that might be used for self-development is drawn out of the country by capitalists abroad.

The apologists for capitalism see it another way. Thus Professor Krugman writes towards the end of his column: “Third-World countries desperately need their export industries. They can’t have those export industries unless they are allowed to sell goods produced under conditions that Westerners find appalling, by workers who receive very low wages.” The eyes of establishment economists are blinded and their minds closed by their faith in capitalism. When capital rules, growing exports from the poor countries are needed to pay off the persistent deficits. Ignored are the possibilities for change in structure and class power in the poor countries, when exports may well be needed to meet the basic needs of all the people. Multinationals and other foreign capital do more than miserably exploit their workers. They are part of the process of keeping the society in bondage, thereby interfering with the possibility of independent development to serve the needs of the people.

Comments are closed.