Many of the informal economies operating in the world today are the offspring of globalization and need to be understood as such. The economic and social prospects for people engaged in informal employment—sometimes referred to as “precarious” and “off-the-books employment”—as well as their families and communities, are substantially inferior to those associated with formal employment, and the current boom of informal economic activity bodes ill for all working people.

Referred to variously as “underground,” “shadow,” “invisible,” and “black” (as in “black market”) economies, many informal economies have developed around the economic survival activities of workers who have been excluded from the formal economy of their nation or region and exploited by entrepreneurs willing to take advantage of their desperation. Initially considered phenomena of the third world and developing nations, informal economies are now expanding rapidly in the free market nations of the western world, including the United States.

Work in the informal economy contrasts sharply with formal employment: wages and working conditions are substandard; there are no guaranteed minimum or maximum hours of work, paid holidays, or vacations; gender, ethnic, and racial discrimination are uncontrolled and systematically exploited; no mandatory health or safety regulations protect workers from injury or death on the job; and workers are denied the traditional benefits of employment in the formal economy: workman’s compensation; health, unemployment, and life insurance; and pensions. Needless to say, few workers join the informal labor force voluntarily—the vast majority are recruited primarily through economic desperation unmitigated by even a minimal social safety net.

Worker participation in the informal economy is a complex phenomenon. While immigrant workers play a significant role in the informal U.S. economy, native workers also participate. These workers in the informal sector include widely divergent groups from professionals who do unreported jobs on the side, and craft workers who exchange work in kind, to marginalized native workers who, because of cutbacks in welfare programs, must accept any work they can find.

The informal sector of the U.S. economy is growing as the working population expands and employment opportunities in the formal economy do not keep pace. Not only are workers being displaced as companies move their operations offshore in search of lower labor costs, but an increasing number of U.S. corporate start-ups are overseas ventures. These current trends contribute to the exclusion of both new and veteran workers from the formal economy.

Los Angeles: A Definitive Case Study

Although no comprehensive national studies of the informal U.S. economy have been published to date, a study of work in the informal economy of the City of Los Angeles by the Economic Roundtable, a nonprofit, public policy research organization, offers an in-depth look at a local informal economy. The full report, Hopeful Workers, Marginal Jobs: LA’s Off-the-Books Labor Force, is available online at http://www.economicrt.org. Since the recently reported case study of Los Angeles’s informal economy presents the most refined estimates of informal employment and its impact available for any specific area of the country, it deserves special attention.

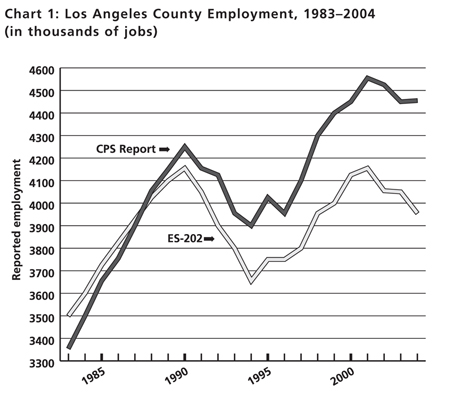

Chart 1 provides a detailed study of informal employment. The CPS line in chart 1 is based on employment status reported by Current Population Survey respondents residing in Los Angeles County. The ES–202 line in chart 1, based on California Employment Development Department records, is specific to California. It represents all wage and salary employment reported by Los Angeles County employers in their payroll tax submissions to the state. The gap between the two lines in chart 1 can be considered a good indicator of informal economic activity.

This chart reveals a widening gap between worker and employer reported employment signaling an ongoing informalization of the Los Angeles County economy that has continued unabated through boom and bust for the last eighteen years.

The most remarkable feature of chart 1 is in the period following the economic recession of 2001. The data indicates that as late as 2004 economic recovery was still out of sight. In spite of that, the informal economy held relatively steady during this period while the formal economy continued in serious decline. The 2005 data, not included in the Economic Roundtable study, indicates a continuation of the same trend. The conclusion of the Economic Roundtable researchers, that the economic stagnation of southern California that was triggered by the recession of 2001 would have been worse without the ameliorating effects of the informal economy, appears to be fully warranted.

In addition to documenting the general trends of informal economic activity, the Economic Roundtable study also offers credible estimates of the actual size of the informal economy in Los Angeles County. These researchers calculated low-range, mid-range, and high-range estimates for the number of county workers in the informal labor force and, after careful consideration, settled on the mid-range estimate of 679,000 workers in 2004. This number represented a substantial 15 percent of Los Angeles County’s labor force in that same year.

The Economic Roundtable researchers used this number to determine the cost of informal employment to the public social safety net in Los Angeles County. Determining that the average annual wage for off-the-books jobs was slightly over $12,000 in 2004, they calculated that the informal economy produced an $8.1 billion payroll. This unreported and untaxed payroll shortchanged the public sector in Los Angeles County by the following amounts:

- $1 billion in Social Security taxes (paid by both employers and workers)

- $236 million in Medicare taxes (paid by both employers and workers)

- $96 million in California State Disability Insurance payments (paid by workers)

- $220 million in Unemployment Insurance payments (paid by employers)

- $513 million in Workers Compensation Insurance payments (paid by employers)

These losses added up to over $2 billion in unpaid payroll benefits and insurance that were needed to fund a minimal social safety net for workers. The payroll tax shortfall is continuing and resistance on the part of California taxpayers to underwrite public relief measures has resulted in the widespread deterioration of social services for informal workers and their families across the state.

Though the Economic Roundtable study is focused primarily on work in the informal economy, researchers point out that informal workers in Los Angeles County spend an estimated $4.1 billion per year that should generate $440 million in sales tax revenue. However these workers purchase many goods and services from informal retailers and service providers who do not collect sales taxes and submit them to the state, further eroding support for the public sector.

The social and political crises of the region are being fueled by the fact that the expanding informal economy in southern California is based on the widespread exploitation of undocumented Mexican and Central American workers. This state of affairs has elevated the issue of illegal immigration in California (and, of course, the nation) to center stage.

The Exploitation of Undocumented Workers

The issue of the exploitation of undocumented workers is fundamental to understanding the informal economy in Los Angeles. While it is true that many native workers and legal immigrants participate in Los Angeles’s informal economy, undocumented immigrants represent the majority of the off-the-books workers. At the same time, while many individuals, both natives and immigrants, participate in both economies, these dual roles should not be allowed to obscure the dominant role of undocumented immigrant workers in Los Angeles’s informal economy.

The Economic Roundtable study substantiates the dominant role of undocumented workers in Los Angeles County when it addresses the question of how many workers in the informal economy are undocumented immigrants and which industries employ them. Based on U.S Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and Census 2000 data, the Economic Roundtable estimates that undocumented immigrant workers make up 61 percent of the informal labor force in Los Angeles County and 65 percent in the city. Census 2000 data also establishes that while there are sizable numbers of Asian and Middle Eastern immigrants in California, the vast majority of the immigrants residing and working in southern California are from Latin America.

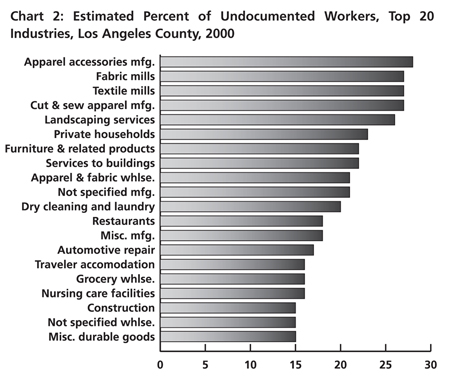

While the proportion of undocumented workers in the informal economy of Los Angeles is truly remarkable, where these workers are employed is also surprising. The top twenty industries employing undocumented immigrants in Los Angeles County are ranked in chart 2. The picture of the informal labor force presented in chart 2 contrasts sharply with popular perceptions of immigrant workers that are based on glimpses of day laborers soliciting on street corners, domestic workers waiting at bus stops, and landscape crews packed into pickup trucks. Derived from INS and Census 2000 data, this chart indicates that a wide array of industries in Los Angeles County systematically exploit undocumented immigrant labor. The Economic Roundtable study reveals that, in fact, the majority of the informal workers labor regularly and out of public view in factories, mills, restaurants, warehouses, workshops, nursing homes, office buildings, and private homes. In actual numbers, the ERT researchers estimate that these top twenty industries in Los Angeles County alone employ over 180,000 undocumented workers.

Most of these undocumented workers are obviously not casual day laborers. The nature of the majority of the jobs listed in chart 2 entails stable relationships between employers and workers and requires extensive community networks to recruit and support those workers.

Although the earnings of immigrant workers in the informal economy are inferior to that of native workers across the board, they do not represent the rock bottom of exploitation—the Economic Roundtable’s breakdown of earnings by gender reveals the severity of the super-exploitation of undocumented women workers in the Los Angeles informal economy.

The Super-Exploitation of Undocumented Immigrant Women

Since this super-exploitation of undocumented women workers takes place almost exclusively out of sight, it all but escapes public attention. However, the Economic Roundtable documents significant employment of undocumented women workers in the top twenty industries that employ the most informal workers. Generally, women tend to work in homes, personal service jobs, and light manufacturing, traditionally low-paying jobs, while men hold the majority of the jobs in transportation, construction, and other relatively higher-paying blue-collar jobs.

Economic Roundtable researchers highlight the super-exploitation of undocumented women workers in the Los Angeles informal economy when they compare wages by gender in specific job categories for the year 1999. For example, in the category of services to buildings, where the gender shares of jobs were exactly equal, men averaged $13,308 while women made an average of $6,869 (51 percent of the earnings of men). Even in private households, beauty salons, department stores, and health care services, jobs clearly dominated by women workers, men were paid more. While women held 75 percent of the jobs in these categories, they earned only 66 percent of the wages of men doing the same work. Overall, the average wage for undocumented women workers in the informal economy of Los Angeles County was $7,630 compared to $16,553 for men. That amounts to only 46 percent of undocumented men’s annual earnings.

The economic basis of Los Angeles’s informal economy can be summed up succinctly—undocumented women workers make less than one-half (46 percent) of what undocumented men workers make, and the average wage of all undocumented workers is less than one-half (41 percent) that of native workers in the same job categories in the formal economy. Even these glaring inequalities underestimate the super-exploitation of informal laborers because they do not account for the other employment benefits that workers in the formal economy receive, which range from 27 to 30 percent of their total employment compensation.

The Economic Roundtable study indicates that the informal sector of the Los Angeles economy, which depends on the exploitation of undocumented workers, has become an integral part of the area’s economy. The implications of this extraordinary case study clearly suggest that the trends of the national informal economy deserve careful reconsideration.

National Trends

Clearly the informal economies of Los Angeles and Los Angeles County are unique. The proximity of southern California to Mexico and the ready access to Mexican and Central American labor have historically shaped the economy, social structure, and culture of the area. The fact that Los Angeles remains the primary destination of Mexican immigrants, both legal and undocumented, is a matter of public record.

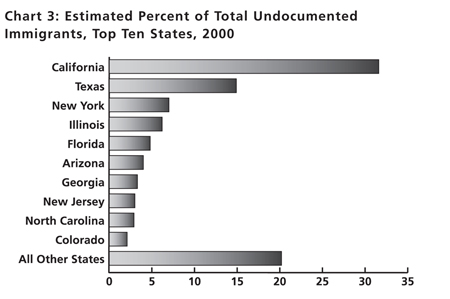

Chart 3 is based on the important Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Office of Policy and Planning study, Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Resident in the United States: 1990–2000, (http://uscis.gov). The INS statistics verify the concentration of undocumented immigrants in California but also reveal that Texas, New York, and Illinois (primarily New York City and Chicago) have considerable concentrations. All of these areas also have sizable established informal economies.

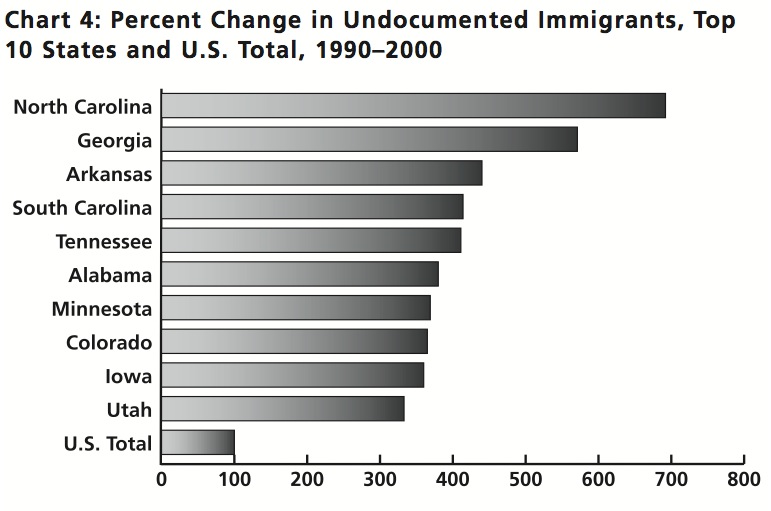

The big surprises in the INS study are the recent trends of worker immigration from Mexico and Central America to other destinations in the United States. These national trends are recorded in chart 4, based on the same INS study as chart 3. This shows that six of the top ten states that experienced the highest growth rate of undocumented immigrants during the last decade of the twentieth century are in the southeastern United States with three states in mid-America not far behind. The phenomenal increase in immigration to the southeast is to the booming metropolitan areas where new construction and service-oriented businesses have created a huge demand for low-cost labor. During the period 1990–2000, the number of undocumented immigrants doubled from 3.5 to 7 million for the United States overall. Current estimates indicate that those immigration trends have accelerated and the nation’s total is now between 11.5 and 12 million (http://www.pewhispanic.org).

The present patterns of illegal undocumented worker immigration in the United States signal a rapid expansion of the national informal economy. The practice of basing the informal economy on the exploitation of undocumented workers, well established in California and Texas, is rapidly spreading across the nation. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates that in March 2005, 7.2 million of the 12 million undocumented immigrants in the United States were working, making up about 4.9 percent of the total work force. Applying the same correction factor to this Pew assessment that the Economic Roundtable researchers applied to employment data in the Current Population Survey for L.A. County, to estimate total employment in the local informal economy, suggests that 8–10 percent of all workers might be employed in the informal economy nationwide

This emerging informal economy signals perennial hard times for the undocumented workers and a continuing war of attrition against the U.S. working class at large.

Harder Times, U.S. Style

Global economic theory discusses informal economies in terms of “restructuring.” This neoclassical and neoliberal theory maintains that all the workers of the world are competing with each other in a zero-sum game. Informal economies arise when the workers in one economic region of the world lose out to the workers in another region and the formal economy of the loser region contracts or collapses. According to this theory, informal economies arise to fill the resulting economic vacuum, and the mechanism of the free market will determine the outcome.

Neoliberal economists argue that displaced immigrant workers, primarily from Mexico and Central America, migrate to the United States and compete with native workers for scarce jobs in a post-industrial economy, as dictated by the “invisible hand” of the “free market.” The ideological cover story for public consumption, meanwhile, is that immigrant workers take the jobs that native workers refuse.

But it is political economics, not free markets, that shape global, national, and local economies. The movement of industrial and service production offshore to take advantage of cheap labor requires the compliance, or outright cooperation, of both home and foreign governments and is therefore a quintessentially political act. Also political is the widespread subversion of immigration and labor law for the sake of profits. These political machinations—not some mythical “invisible hand”—are the engines of the informal economy in the United States.

The burgeoning informal economy in the United States is introducing new elements into familiar historical patterns of exploitation. While the U.S. economy has traditionally been fueled by immigrant labor, the current dependence on undocumented labor is unprecedented. Although the masses of Western and Eastern Europeans who immigrated to do America’s dirty work in the past were rewarded with citizenship for their sacrifices, there is no indication that the current Mexican and Central American workers can expect the same. Naturalization is not part of the deal. Dirty and poorly paid work in the contemporary informal economy is not an initiation into the mainstream U.S. working class. The current wave of undocumented immigrants who work in the informal economy today are more likely than not to stay in the informal U.S. economy—as long as they are needed.

The U.S economy is indebted to undocumented immigrant workers, but there is no indication that the debt is going to be paid. The proposed “guest worker” programs currently being debated in Congress are nothing more than reruns of the Bracero Program that lasted from 1942 to 1964, and the debts owed to workers from that program are still outstanding. The contemporary strategy is to use Mexican and Central American workers displaced by NAFTA as long as possible. If, or when, they are no longer needed, they can be repatriated. It happened to their compatriots who were uprooted from their homes and communities and driven across the border at the onset of the Great Depression and again during the paramilitary repatriation campaign designated “Operation Wetback” in the recession that followed the Second World War.

The current boom in the informal economy bodes no better for native workers in both the informal and formal sectors of the U.S. economy. Real wages, benefits, and standards of living continue to decline for all workers and the labor movement is stalled. Realizing the American Dream through hard work in a promising job is becoming a remote possibility rather than an accessible opportunity. And there’s nothing like the naked specter of wage slavery in the informal economy and the ghettoization of the poor to keep the expectations of all workers in check. The revolution of rising expectations that gripped workers and minorities in the 1960s has been overshadowed by the prospect of pauperization.

Until the labor movement develops the solidarity necessary to confront the current assault of capitalism, the expanding informal economies of the world will continue to impoverish the lives of all working people. The call to all workers of the world to unite has never been more urgent than it is today.

Comments are closed.