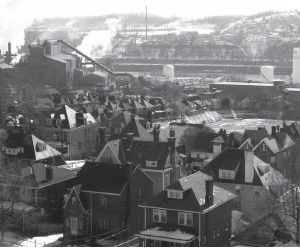

As far as scenic ruins go, the Pittsburgh metropolitan area sets a high standard. The natural beauty of the Monongahela Valley and the built legacy of deindustrialization make gorgeous scenery out of blue-collar defeat.

Beauty is no compensation for lost jobs though. The old steel towns of this region have been imploding for decades. No place has lost a greater share of its population than Braddock, Pennsylvania, just outside Pittsburgh. This ravaged, near-empty stretch of abandoned homes, storefronts, and buildings was once a storied cornerstone of the industrial age. After losing 90 percent of its peak population, today it looks more like the nightmare at the end of the American Dream.

A concrete, bunker-like building sits back from the rubble on Library Street there. A freight container has been stacked on top of it, adding living space to the building in the most conspicuous way possible. The door is marked with a sticker: a parody of the popular street art stencils of Andre the Giant’s face, but with the word “MAYOR” in block letters where the stencil would ordinarily read “OBEY.” Through that door and up a flight of stairs, a massive, six-foot, eight-inch man with a shaved head and goatee is perched on leather furniture amid avant-garde decor, fielding phone calls and drinking a bottle of Yuengling. It’s as if Andre the Giant himself has come back to life and moved to the Monongahela Valley to do advanced degrees in urban studies and interior design.

It’s not your average mayoral residence. But Braddock is not your average Pennsylvania town, and its mayor, John Fetterman, is as far from being an average mayor as you can get.

“I first came to this town as an Americorps volunteer working with at-risk youth. And I was just amazed with the place, its history and architecture,” says Fetterman. The mayor is an imposing character; he resembles a professional wrestler but speaks with the articulate voice of the masters degree in public policy he got at Harvard. Using his left arm (which bears a large tattoo of Braddock’s zip code), Fetterman gestures toward the rubble-strewn wasteland around Library Street, as if the view explains exactly why he fell under Braddock’s spell as a young man.

A native of another industrial Pennsylvania city, Fetterman had seen the bombed-out look of old factory towns before. But Braddock is more devastated—and strangely picturesque—than perhaps any other place in the state of Pennsylvania. The challenges and potential that remained in this once-prosperous steel town spoke to him. He continues, “So after completing my degree, I had an opportunity to continue working at the same program back here, and right away I started pouring my salary into buying some of the amazing buildings that were on the verge of collapse.”

In the process he began promoting his adopted home to friends, spreading the word to artists that live-work spaces could be found in Braddock for little money. With his appetite for the challenge growing with each small success, Fetterman jumped at the chance to run for the part-time job of being the community’s mayor in 2005.

After winning the Democratic primary there by just one vote, John Fetterman became the mayor of an economic disaster zone. He began an unorthodox reconstruction program, calling on urban pioneers to help rebuild a devastated place, but not for the gentrified benefit of real estate speculators. In a part of the country where Braddock is only the hardest-hit example of hundreds of de-industrialized places, any success at revitalization through green design and the arts here might light a path for other small rust-belt cities out of poverty and population loss. But larger questions about the lack of jobs cast a shadow over such hopes, and a new expressway proposed to run straight through Braddock threatens to kill the town’s last chance at resurrection in its crib.

Mayor of a Ghost Town

“Statistically speaking, Braddock is an outlier among outliers. I don’t know of any other place in the rust belt that had a 90 percent population loss,” Fetterman notes, on one of the countless tours he gives to anyone who will listen. He goes on, “Pittsburgh, for instance, still has an economy. So the powers that be there are trying to break the unions and reorganize the city’s finances. We don’t even have finances.”

Braddock’s existence is a legacy of the Edgar Thompson Steel Works, which in 1875 was the first major steel mill built in the country. Many more mills were subsequently built in the Monongahela Valley, making it the world capital of steel production. Today, however, the Edgar Thompson is the last one still running in the valley, a lonely survivor of the U.S. steel industry’s crisis in the 1980s. Though Braddock was originally built up to house the mill’s workers, none of the mill’s nine hundred odd remaining employees today still live there. “The mills’ principal contribution to the town at this point is, well, pollution,” says Fetterman of the steel plant, visible from the top floor of his home. He adds, “Braddock has the highest rate of child asthma in the region.”

The town has fewer than 3,000 residents left, according to the 2000 census (down from a peak population of 20,879), many of whom are elderly or struggling with health issues, addiction, or poverty. For those who remain, Braddock has little to offer in the way of work. Indeed, many of the town’s few remaining jobs are filled by blue-collar commuters from Pittsburgh or the suburbs.

Lifelong Pittsburgh resident and postal worker Leanne O’Connor describes commuting to work in Braddock: “The post office had transferred me to work out of the location on the far edge of Braddock. Taking the bus there to work up Braddock Ave. every day the driver would always tell me I should try to work somewhere different, that it was too dangerous for me here.” Leanne took him up on his advice, after being mugged at knifepoint on that bus the following week.

“When I was a little kid in the eighties, whenever my family drove through Braddock on our way somewhere I’d be amazed. All the abandoned buildings, I’d never seen anything like that,” O’Connor remembers. “My parents just told me, ‘this is a ghost town.’”

Out of the Furnace and into the Fire

Braddock is a unique place, not only in the hardship it faces today, but also in its historic significance. What Independence Hall is to the American Revolution, this area is to our country’s century of steel. Robber baron Andrew Carnegie built his first steel mill in Braddock, and across the river is the spot where he once sent a private army to stage an armed attack on the striking workers of his Homestead plant. Frick Park, up the hill from Braddock, is named for the hated factory boss who a young anarchist tried to assassinate in revenge for the attack on Homestead. Carnegie, nervous about his public image, built the first of his many public libraries in Braddock, where it still sits across the street from Fetterman’s house.

The area has perhaps more labor history per square mile than any other place in the nation. Up Braddock Avenue to the east are electronics factories where America’s domestic Cold War was fought out with fists and union elections between pro- and anticommunist workers. A few miles west in Pittsburgh is the downtown office building where the CEO of US Steel and his arch-nemesis, John L. Lewis of the Steelworkers Organizing Committee, used to tensely ride in the same elevator to work every morning. America has many industrial places, of course. But just as the Declaration of Independence was only signed in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, only here did steelworkers fight and win the Battle of Homestead on July 5, 1892.

These Monongahela Valley cities grew up as oppressive company towns, built to house the immigrant workforce of the nineteenth century’s mines and mills. With their flaming smokestacks and climate of fear and toil, the comparison newcomers made most often was to hell. But over the years, residents transformed them into bastions of working-class prosperity and democracy, through lifetimes of work and saving—and the titanic struggle for collective bargaining and labor unions.

One of the central novels of the immigrant experience in industrial America, Out of This Furnace, was set in Braddock. In it, author Thomas Bell—son of a Braddock immigrant family and a worker in the mills himself—follows several generations of the Dobrejcak family through the ceaseless hardships of industrial life in the Monongahela Valley, culminating in the victory of the steelworkers union in the late 1930s.

Closing on such a note was no mere Popular Front triumphalism. For working people like the Dobrejcaks of Braddock, industrial unions brought a sea change in living standards, social status, and political power. The American Dream only came to the Monongahela Valley because its families would not stop working and fighting for it. Since most of the landmarks of that struggle lie in unmarked ruins around Braddock today, works like Out of This Furnace are the last reminders of how America was built in places like this.

Braddock’s contributions to the social realist canon have continued in our time, particularly with the films of Tony Buba. Buba—like Bell, a son of an immigrant millworker family—grew up in Braddock when it was the relatively prosperous picket-fence community that generations of workers had struggled to create. After putting in some time in the factories of the region as a young man, Buba went to college to study filmmaking amid the cultural ferment of 1968.

“When I’d come back to visit my family in town in the seventies, the changes in Braddock were starting to be really noticeable,” Buba recalls. “You know how if you haven’t seen your grandparents in a few years, and then when you see them again they just look so old. That’s what seeing Braddock again was like when I came home from college. I thought, well, here’s my subject material. I thought I had to document this way of life before it was gone.”

As Buba points out, the town was in part a victim of its own successes. “After a couple generations of steelworkers having pretty good union contracts, plus the GI Bill, it became possible for workers to move out of the area. I mean, these were small homes built right next to all the noise and dirt of the mill. Workers started being able to have a house a little further out in the suburbs, and a car to drive to work in. Which was an example of success, really, a thing that was basically good.” The rise of strip malls and suburban big box stores also decimated the old small businesses of Braddock’s once-famous retail corridor.

The decline Buba began to document took an ugly, unexpected turn in the 1980s when crisis in the steel industry brought hundreds of thousands of layoffs in the Monongahela Valley. “Believe it or not,” Buba continues, “in the late seventies we thought that Braddock had reached its rock bottom. There were studies done then that said it would drop to twelve thousand people and that would be it!” Buba laughs darkly.

Much worse was to come. The steel industry entered a death spiral of layoffs, plant shutdowns, reductions in pay and benefits, strikes, and eventually a wholesale shedding of its workforce. The Pittsburgh region was racked with home foreclosures and evictions, bankruptcies, suicides, alcoholism, violence, and despair. Braddock, having already begun to decline for several decades before steel’s crisis in 1984, found it could sink much further.

These events hurt everyone in the region, but some communities bore greater burdens than others. Buba’s film Struggles In Steel chronicles the historic battle African Americans had waged—with both the steel companies and elements in the steelworkers union—to gain equal access to the good jobs in the plant. By the late seventies this progress had finally resulted in substantial numbers of black workers finally breaking into job seniority (blacks had been denied access to better jobs because their job seniority counted for nothing when they bid on a different job) and shop steward leadership positions, only for all to be lost in the plant closings.

Beyond job racism, there was a residential aspect to the situation of blacks in the Monongahela Valley. As Buba notes, “There was redlining. Heck, the GI Bill which got a lot of people their first home, really, it was made to be for white guys to move to the suburbs.” The African-American community in the area was in the doubly precarious situation of not having had the benefit of generations of industrial employment to build up savings and seniority before the plant closings began, and being redlined out of homes in other areas. Alongside the steel crisis was the country’s rightward turn and Reagan-era cuts in social spending. With the plagues of crack cocaine, HIV/AIDS, and endemic street violence added, places like Braddock faced a “perfect storm” of urban devastation.

Tony Buba’s cinematic requiems for Braddock may not wind up being the best-known films set there, however. The film version of Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic masterpiece The Road, starring Viggo Mortensen, shot its opening scenes in Braddock. Booking a high-profile role is a real coup for a town desperate for any activity at all, and comes thanks to the mayor’s constant hustle to promote Braddock to the country’s creative class.

The film offers a sad bookend to Braddock’s historic arc. Once the setting for a novel in which immigrants change a hellish company town into a humble but solid home through their work ethic and collective struggle, Braddock today is the realistic-looking backdrop for another writer’s realist description of America after nuclear holocaust.

The question facing Mayor Fetterman and Braddock’s remaining residents is: When a town goes from Out of this Furnace to The Road in the space of three generations—from hell to heaven and then back to hell again—what next?

Green Jobs and Basketball Courts

“We’ve been taking a two-pronged approach,” Fetterman says to answer this question. “On one hand we have to make improvements in providing functional services and urban space for the existing resident base. When I took office, Braddock had no basketball court. No parks. No place to even walk your dog, except the street.”

Given such a lack of the basic amenities of urban life, the first three years of his term have seen some quick progress. Fetterman ticks off the accomplishments as he drives by them on another impromptu tour of town: Braddock’s first basketball courts have been constructed, and its functional green space increased substantially with abandoned lots renovated into parks and gardens. A community-supported agriculture project called Pittsburgh Grow now operates an urban farm under the bridge into town.

Good intentions and hard work only go so far without resources. Fetterman points out, “Braddock is an Act 47 community.” The term refers to the Pennsylvania legislature’s provisions for municipalities (many of them old steel towns like this one) that no longer have the tax base to support themselves. He describes the facts of life for a long-bankrupt town with a disarming lack of spin: “We wouldn’t even have money for 911 service here, if we didn’t get a grant for it from the state.”

Considering this reality, Fetterman continues, “So, the second half of the work I try to do is bring new things in. New people, new energy, new economic activity. Because if we cannot start to replace the people and the tax base that’s been lost, then there’s only so much we can change.” Fetterman has been promoting the town to artists and urbanists seeking affordable live-work spaces away from the pretensions and costs of hipper cities like New York.

“We’ve had about twenty newcomers this way so far. That number is still small,” the Mayor concedes, “But what I think is important to look at is that these are creative people who are coming from what are called key cities—places like Providence, San Francisco, New York City, Boston. If people are making a choice to leave cultural capitals like that for a place like here, which does not necessarily have the amenities they’re accustomed to, I think it says something good for our ability to repopulate Braddock.”

Fetterman’s leg of the Braddock tour then ends up at the site of an old, long-abandoned Catholic school and convent that he and some of those new citizens of Braddock are renovating into an art gallery. Michael LeFevre—a young commercial painter who moved here with his wife in order to buy a home they would not have been able to afford back in Portland, Oregon—is lending a hand to finish the building’s ceiling. Two more Braddock revivalists, Jeb Feldman and Helen Wachter (a newcomer and a lifelong resident of the region, respectively) show off the fruits of their labor, reviewing the precious and historic architecture that has been saved and put to new use.

Feldman—who arrived in Braddock several years ago at Fetterman’s invitation to serve in the entirely voluntary post of deputy mayor—goes to great lengths to emphasize the respectful intentions of newcomers like himself. Artists moving in to poor urban neighborhoods like this one often have the unintended effect of sparking real estate development that displaces existing residents, and although Braddock has lost most of its people, there are still three thousand reasons to be worried about gentrification there. Feldman insists, however, “I’ve heard people we know in other places in Pittsburgh kind of scoff at what we’re doing, and say they think we’ll displace people. But I have never heard that from anyone who actually lives here.”

Longtime North Braddock resident and executive director of the Braddock Carnegie Library, Vicky Vargo, is pleased with the work of the newcomers, but does acknowledge some concern about their potential impact. “I do think it’s possible, that they may get so many people to move here that it changes things. But what I think is important,” she continues, “is that they don’t storm in, use the town up, and then move on to the next hip spot later on.” The new Braddock pioneers that she’s met, however, “have been very respectful. The ones I have met went out of their way to ask the community that has stuck it out here what their needs are, what their vision for the town is.”

Indeed, if Fetterman’s strategy is to both improve urban services for the existing old residents while also attracting creative new ones, some of the most dynamic results have come from mixing the two strategies. One new resident put his skills as a muralist to work with local kids on making a giant new “Welcome To Braddock” mosaic sign. Fetterman has championed the classic remaining small businesses of Braddock to newcomers, and the Elks Lodge bar has replenished its customer base by swearing in dozens of young new members and hosting punk shows. So many do-it-yourself renovations are under way in churches, stores, homes, and other buildings that hardly a block is untouched by the civic energy of Fetterman’s incoming Braddock enthusiasts.

Tony Buba doubts the efforts will lead to gentrification. “The town lost 90 percent! They’ll never fill all the buildings. This whole region has had more empty properties than it will ever be able to fill, ever since the eighties,” he says. Certainly Braddock is a bit more off the beaten path than the upwardly mobile real estate of Brooklyn or San Francisco’s Mission District. It’s a very long bike ride from here to Pittsburgh’s college campuses (even on a fixed-gear bike), and the Monongahela Valley does not exactly have as many house-hunting yuppies as the Silicon one in California.

Buba compares the newcomers to the local activists who first re-opened the library Vicky Vargo works at, saying, “In the late seventies, a group of activists got together to reopen the abandoned Carnegie Library, and they had a lot of great programs out of there too. It was all part of a time here, when a lot of the socialists from the sixties…were getting jobs in the steel mills, getting involved in the union,” and producing a variety of media and art on blue-collar life in the area.

While Buba does not fear an overabundance of success from the current efforts to revive Braddock, he does see a gulf between the newcomers and the remaining residents of the town. “Honestly, if you compare what these kids are doing to that last wave of activism,” he says, “the group that did the library had a lot more buy-in from the black community in Braddock. Because, in the old days, blacks weren’t allowed in that library. So reclaiming the library was a project that generated a lot of enthusiasm at the grassroots. There was an energy from the civil rights movement and everything else. I don’t know that I see that these days.” For Buba, Braddock’s future at this point comes down to jobs. “To really bring the area back to what it once was, people need solid well-paying jobs, families need a good school district.”

Vargo agrees, and points out that the bread-and-butter concerns of the town’s older residents don’t necessarily get quite the media attention the flashier artistic endeavors do. Pointing to a redevelopment at the site of another old abandoned factory at the edge of town, she says, “The development at that site is supposed to include an industrial park, and new housing construction and a park. So we may be able to get back some economic base to keep the young people here. If that connects to the projects the mayor has gotten going, I think we could be seeing some real improvement.”

Mayor Fetterman has put a great deal of his hustle into job creation, as well. “With our contacts in groups that do youth service jobs, we’ve set up a summer jobs program for young people here.” Fetterman— normally a reserved, intimidating persona—positively glows when he speaks about the summer jobs. “So in 2006 we had jobs for fifty teen-agers. They decided on their focus, and the program turned an abandoned lot into a garden in a single summer. We had a 90 percent retention rate,” Fetterman boasts. “Even Google doesn’t keep 90 percent of its employees!”

Fetterman continues, “Green jobs and the arts are what drive youth employment in Braddock now. Which marries social welfare to greening, which heretofore has just been kind of an upscale consumer choice. Next summer we’ll have, hopefully, seventy-five jobs positions. We need more, because last summer we had ninety applications for the fifty jobs.” Gangs and the drug trade are some of the primary employers of young people, besides Fetterman’s program, and several young people die in street violence each year. Fetterman has the dates of each death tattooed on his right arm, opposite the tattoo of Braddock’s zip code. He concludes with, “What keeps me up at night is, what happened to the other forty kids that summer we didn’t have enough jobs for?”

The Last Stake In Braddock’s Heart

There is a strong environmental subtext to Fetterman’s program in Braddock. The first new businesses to open up there under Mayor Fetterman’s time in office are two workshops—one that converts diesel engines to run on the ecologically sustainable alternative “bio-diesel,” and another that builds furniture from recycled materials. Moreover, Braddock has gone from having no parks to having both a large urban garden and farm—and Fetterman sits on the board of the agency working to turn the nearby abandoned Rankin steel mill into a national park and open-air museum of the area’s industrial history.

Beyond such grassroots efforts, there is a larger ecological vision implied in the entire project of reclaiming devastated urban space. In an age of skyrocketing fuel prices and global warming, in the coming decades the United States will be forced to cut its carbon footprint to a sustainable size. However, the built environment the country has constructed in the past fifty years will make such frugality incredibly difficult. The miles and miles of suburban sprawl that extend from rust belt to sun belt, full of enormous McMansions and ninety-minute commutes, will be a source of deep economic pain as energy costs continue rising.

Rebuilding Braddock represents a different plan: to stay in the cities we’ve already built. Salvaging and renovating the town’s crumbling, beautiful, human-scale architecture is the ultimate in recycling. As Fetterman reiterates again and again, “In Braddock we can find adaptive new uses, for an urban world America left behind.”

Such an innovative environmentalism makes the current threat to Braddock’s existence an especially bitter pill. Despite so much potential for a greener, economically viable Braddock, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission is dusting off old plans to run a new four-lane toll road expressway straight through the town. The proposed Mon-Fayette Expressway would provide some drivers with a faster commute, at the expense of demolishing a good bit of Braddock and its neighbors.

Fetterman has little more than exasperated outrage for the fact that the first public works project to come to Braddock in decades is to tear up the town. “This expressway is a thirty-five-year-old monstrosity, and comes from an antiquated Robert Moses-style mentality to urban planning that other places are finally leaving behind,” Fetterman says. “The idea seems to be, to underestimate the costs, get it approved, and run it through where Braddock Avenue is today.”

For an individual who has devoted so much effort to reviving a town many wrote off as a lost cause, Fetterman’s pessimism about Braddock under the Mon-Fayette seems uncharacteristic and vivid. “That expressway would be the last stake in the heart of Braddock.”

Comments are closed.