In a 1963 talk on “The Pollution of Our Environment” Rachel Carson drew a close comparison between the reluctance of society in the late twentieth century to embrace the full implications of ecological theory and the resistance in the Victorian era to Darwin’s theory of evolution:

As I look back through history I find a parallel. I ask you to recall the uproar that followed Charles Darwin’s announcement of his theories of evolution. The concept of man’s origin from pre–existing forms was hotly and emotionally denied, and the denials came not only from the lay public, but from Darwin’s peers in science. Only after many years did the concepts set forth in The Origin of Speciesbecome firmly established. Today, it would be hard to find any person of education who would deny the facts of evolution. Yet so many of us deny the obvious corollary: that man is affected by the same environmental influences that control the lives of all the many thousands of other species to which he is related by evolutionary ties (Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson, pp. 244–45).

There are numerous reasons for this common failure to acknowledge the ecological basis of the human condition. Many have seen this as a deep cultural flaw of Western civilization, flowing out of the concept of the “domination of nature,” the idea that nature exists to serve humans and to be a servant to humans. But a large part of the answer as to why contemporary society refuses to recognize the full human dependence on nature undoubtedly has to do with the expansionist logic of a capitalist system that makes the accumulation of wealth in the form of capital the supreme end of society.

Orthodox economics, as is well known, defines itself as a science for the efficient utilization of scarce goods. But the goods concerned are conceived narrowly as market commodities. The effects of the economy in generating ecological scarcities and irreversible (within human time frames) ecological degradation are beyond the purview of received economics, which, in line with the system it is designed to defend, seldom takes account of what it calls “external” or “social” costs.

Capitalism and its economists have generally treated ecological problems as something to be avoided rather than seriously addressed. Economic growth theorist Robert Solow wrote in the American Economic Review in May 1974, in the midst of the famous “limits to growth” debate, that, “if it is very easy to substitute other factors for natural resources, then there is in principle no ‘problem.’ The world can, in effect, get along without natural resources, so exhaustion is just an event, not a catastrophe.”

Solow, who later received the Nobel Prize in economics, was speaking hypothetically and did not actually go so far as to say that near–perfect substitutability was a reality or that natural resources were fully dispensable. But he followed up his hypothetical point by arguing that the degree of substitutability at present is so great that all worries of Doomsday ecological prophets could be put aside. Whatever minor flaws existed in the price system, leading to the failure to account for environmental costs, could be cured through the use of market incentives, with government playing a very limited role in the creation of such incentives.

What had outraged orthodox economists such as Solow, when a group of MIT whiz kids first raised the issue of the limits to growth in the early 1970s, was that the argument was premised on the same kinds of mathematical computer forecasting models, pointing to exponential growth trends, that economists frequently used themselves. But in this case, the focus was on exponential increases in the demands placed on a finite environment, rather than the magic of economic expansion. If the forecasting of the limits to growth theorists was full of problems, it nonetheless highlighted the truism—conveniently ignored by capitalism and its economists—that infinite expansion within a finite environment was a contradiction in terms. It thus posed a potential catastrophic conflict between global capitalism and the global environment.

Capitalist economies are geared first and foremost to the growth of profits, and hence to economic growth at virtually any cost—including the exploitation and misery of the vast majority of the world’s population. This rush to grow generally means rapid absorption of energy and materials and the dumping of more and more wastes into the environment—hence widening environmental degradation.

Just as significant as capitalism’s emphasis on unending expansion is its short–term time horizon in determining investments. In evaluating any investment prospect, owners of capital figure on getting their investment back in a calculable period (usually quite short) and profits forever after. It is true that a longer–term perspective is commonly adopted by investors in mines, oil wells, and other natural resources. In these areas the dominant motives are obviously to secure a supply of materials for the manufacture of a final product, and to obtain a rate of return that over the long run is exceptionally high. But even in these cases the time horizon rarely exceeds ten to fifteen years—a far cry from the fifty to one hundred year (or even more) perspective needed to protect the biosphere.

With respect to those environmental conditions that bear most directly on human society, economic development needs to be planned so as to include such factors as water resources and their distribution, availability of clean water, rationing and conservation of nonrenewable resources, disposal of wastes, and effects on population and the environment associated with the specific locations chosen for industrial projects. These all represent issues of sustainability, i.e., raising questions of intergenerational environmental equity, and cannot be incorporated within the short–term time horizon of nonphilanthropic capital, which needs to recoup its investment in the foreseeable future, plus secure a flow of profits to warrant the risk and to do better than alternative investment opportunities.

Big investors need to pay attention to the stock market, which is a source of capital for expansion and a facilitator of mergers and acquisitions. Corporations are expected to maintain the value of their stockholder’s equity and to provide regular dividends. A significant part of the wealth of top corporate executives depends on the growth in the stock market prices of the stock options they hold. Moreover, the huge bonuses received by top corporate executives are influenced not only by the growth in profits but often as well by the rise in the prices of company stock. A long–run point of view is completely irrelevant in the fluctuating stock market. The perspective in stock market “valuation” is the rate of profit gains or losses in recent years or prospects for next year’s profits. Even the much–trumpeted flood of money going into the New Economy with future prospects in mind, able momentarily to overlook company losses, has already had its comeuppance. Speculative investors looking to reap rich rewards via the stock market or venture capital may have some patience for a year or so, but patience evaporates very quickly if the companies invested in keep having losses. Besides investing their own surplus funds, corporations also borrow via long–term bonds. For this, they have to make enough money to pay interest and to set aside a sinking fund for future repayment of bonds.

The short–term time horizon endemic to capitalist investment decisions thus becomes a critical factor in determining its overall environmental effects. Controlling emissions of some of the worst pollutants (usually through end–of–pipe methods) can have a positive and almost immediate effect on people’s lives. However, the real protection of the environment requires a view of the needs of generations to come. A good deal of environmental long–term policy for promoting sustainable development has to do with the third world. This is exactly the place where capital, based in the rich countries, requires the fastest return on its investments, often demanding that it get its initial investment back in a year or two. The time horizon that governs investment decisions in these as in other cases is not a question of “good” capitalists who are willing to give up profits for the sake of society and future generations—or “bad” capitalists who are not—but simply of how the system works. Even those industries that typically look ahead must sooner or later satisfy the demands of investors, bondholders, and banks.

The foregoing defects in capitalism’s relation to the environment are evident today in all areas of what we now commonly call “the environmental crisis,” which encompasses problems as diverse as: global warming, destruction of the ozone layer, removal of tropical forests, elimination of coral reefs, overfishing, extinction of species, loss of genetic diversity, the increasing toxicity of our environment and our food, desertification, shrinking water supplies, lack of clean water, and radioactive contamination—to name just a few. The list is very long and rapidly getting longer, and the spatial scales on which these problems manifest themselves are increasing.

In order to understand how the conflict between ecology and capitalism actually plays out at a concrete level related to specific ecological problems, it is useful to look at what many today consider to be the most pressing global ecological issue: that of global warming, associated with the “greenhouse effect” engendered when carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse gases” are emitted, trapping heat within the atmosphere. There is now a worldwide scientific consensus that to fail to stop the present global warming trend will be to invite ecological and social catastrophe on a planetary scale over the course of the present century. But little has been achieved thus far to address this problem, which mainly has to do with the emission of fossil fuels.

What has blocked the necessary action? To answer this question we need to look at the specific ways in which the capital accumulation process has placed barriers in front of the main international diplomatic effort—the Kyoto Protocol—aimed at slowing down and arresting the global warming trend.

The Failure of the Kyoto Protocol

International efforts to control greenhouse gas emissions began in the early 1990s. These early attempts to create a climate accord produced the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed upon in 1992. The UNFCCC consisted of voluntary emission targets on the part of states. The failure of states to reduce emissions under this regime led to further negotiations resulting in the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which for the first time established “legally binding” reductions in greenhouse gas emissions of 5.2 percent below 1990 levels, by 2008–2012, for all industrialized countries. The European Union (EU) under this agreement was required to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 8 percent below 1990 levels, the United States by 7 percent, and Japan by 6 percent. In line with a prior agreement in the climate negotiations (known as the Berlin Mandate) developing countries, including China, although parties to the agreement, were to remain out of this initial stage in emission reductions.

Subsequent negotiations on the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol from 1997 to 2001 focused mainly on two sticking points: provisions for tradable emission permits, which would allow countries to comply with emission reductions by purchasing emission permits from countries that did not need them, and inclusion of allowances for “carbon sinks,” which would provide emission credits for forests and farmlands. The European Union resisted both proposals as thinly veiled attempts to disguise real failures to meet the emission reduction targets. Support for these measures came from the United States, Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Negotiations broke down at the Hague in November 2000, when both sides refused to give in on this dispute.

In March 2001, with these issues still unresolved and with no major industrial country yet having ratified the agreement, the Bush administration declared that the Kyoto Protocol was “fatally flawed” and announced that it was unilaterally pulling out of the climate accord.

Nevertheless, negotiations designed to prepare the way for ratification of the Kyoto Protocol went forward in July 2001 in Bonn. For the treaty to come into force it had to be ratified by countries accounting for 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. This meant that without U.S. participation, eventual ratification by Japan, Canada, and Australia was essential. Under these circumstances, the European Union was forced to give way on point after point in the negotiations—adopting the very positions that the United States (along with Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) had previously advanced at the Hague.

Although the Kyoto Protocol was kept alive in Bonn, despite the exit of the United States, it was shot full of holes, belying the targeted reductions in emissions. Farmlands and forests were to be treated as carbon sinks, resulting in credits in emission reduction. In effect, countries would be counted as having “reduced emissions” simply for watching their trees grow. Tradable pollution permits were to be allowed, enabling countries like Japan, Canada, and Australia, which had increased their greenhouse emissions substantially since 1990, to purchase emission permits from countries like Russia that, due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and most of its industrial structure, had experienced dramatic declines in emissions since 1990. The sole penalty for failing to meet emission reduction targets would be that a country’s targets in the next round would be increased by a certain percentage. Proposals to institute reparations for damage to the climate, to be paid by those countries that did not meet the targeted reductions, were dropped. In a major concession to Japan, the “legally binding” character of the original agreement was also dropped in favor of language that said the accord was “politically binding.” The very thing that had distinguished the Kyoto Protocol from the original UNFCCC—the establishment of “legally binding” reductions in emissions—was thus abandoned.

The refusal of the United States, which alone accounts for a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, to remain a party to the climate accord was the most glaring failure of the agreement arrived at in Bonn. On June 11, 2001, President George W. Bush delivered a speech that strongly reiterated the policy, adopted in March by his administration, of refusing to back the Kyoto Protocol. In doing so, he made more definite a U.S. position already evident during the Clinton administration—when all action to obtain U.S. ratification of the climate treaty had come to a halt in the face of the opposition of the U.S. auto–industrial complex (which meant that there was zero support for ratification of the accord within the U.S. Senate).

What made Bush’s reiteration of U.S. opposition to the climate accord in June 2001 so revealing was how he dealt with a report from the prestigious National Academy of Sciences (NAS). The administration had previously insisted on the need for further research into climate change, and had called upon the NAS to examine the present state of climate science (specifically the research results of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]) and deliver a report to the administration.

Searching desperately for some kind of scientific rationale for its claim that an international accord to combat global warming was unwarranted, the Bush administration had written to the NAS: “The administration is conducting a review of U.S. policy on climate change. We seek the Academy’s assistance in identifying the areas in the science of climate change where there are the greatest certainties and uncertainties. We would also like your views on whether there are any substantive differences between the IPCC Reports and the IPCC summaries. We would appreciate a response as soon as possible.”

The Bush administration had thus called upon the NAS to determine whether the IPCC, whose reports were written by the top climate scientists in the world, had somehow created a politically determined set of conclusions not merited by the underlying science—or worse still, that the science had been politically tampered with, as the Global Climate Coalition (the main lobbying organization for corporations opposed to the Kyoto Protocol) had been arguing.

Days before Bush’s June 11, 2001, speech the NAS had delivered its report, Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions, to the president, strongly reconfirming what the IPCC in its various reports had already established, that global warming as a result of human activities is a reality and a growing threat to the stability of the biosphere and thus to life on earth as we know it. On all of this, the NAS left no room for doubt, declaring in the very first paragraph:

Greenhouse gases are accumulating in Earth’s atmosphere as a result of human activities, causing surface air temperatures and subsurface ocean temperatures to rise. Temperatures are, in fact, rising. The changes observed over the last several decades are likely mostly due to human activities, but we cannot rule out that some significant part of these changes is also a reflection of natural variability. Human–induced warming and associated sea level rises are expected to continue through the 21st century. Secondary effects are suggested by computer model simulations and basic physical reasoning. These include increases in rainfall rates and increased susceptibility of semi–arid regions to drought. The impacts of these changes will be critically dependent on the magnitude of the warming and the rate with which it occurs.

The NAS not only supported the IPCC reports, but also indicated that the IPCC’s Summary for Policy Makers had not distorted the underlying scientific findings; that no modifications in the scientific text of any significance had been made following the meetings of the lead authors with governmental representatives; and that those minor changes made were documented and included with the consent of the convening lead authors. All claims that the IPCC process had been politically tampered with were therefore false.

The NAS report on Climate Change Science left the Bush administration with no alternative but to admit to the seriousness of the problem, or to be seen as having turned its back on science altogether. Thus President Bush in his June speech acknowledged the existence of significant global warming arising from carbon dioxide emissions along with other greenhouse gases, and conceded that “the National Academy of Sciences indicates that the increase is due in large part to human activity.” He went on, however, to point out that there were many uncertainties in the specific projections on climate change and their effects, and in technological prospects for reducing the build–up of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. The Kyoto Protocol itself, he said, was flawed for two reasons: (1) it “would have a negative economic impact [on the U.S. economy] with layoffs of workers and price increases for consumers” and (2) it did not include developing countries like China and India, both of which are among the largest contributors to global warming.

The Kyoto Protocol, with its mandatory cutbacks in greenhouse gas emissions, was clearly beyond what U.S. capital and its state were willing to accept. With no scientific basis for rejecting the climate accord, the U.S. government was forced to admit the true nature of its objection: that in its view the cost to the U.S. economy of cutting such emissions, and particularly emissions of carbon dioxide, the leading greenhouse gas, was simply too high a price to pay.

But why was the United States so reluctant to agree to reduce greenhouse gas (particularly carbon dioxide) emissions to below the 1990 level, while Europe seemed more than willing to support the Kyoto Protocol? Was the refusal to go along with the climate accord a peculiarity of the United States—its corporations and government—rather than reflecting conditions endemic to capitalism itself?

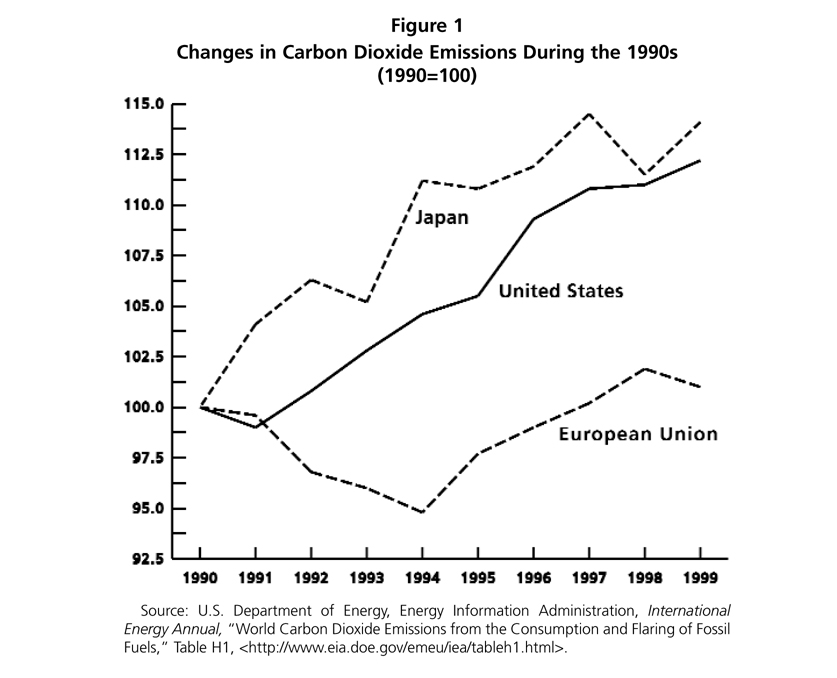

Here it is useful to look at the record of carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels for the United States, the European Union and Japan over the 1990s (see Figure 1). In April 1993 President Clinton declared that the United States would stabilize its greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by the year 2000 by relying on an array of voluntary measures. Instead, during the 1990s U.S. carbon dioxide emissions from the combustion and flaring of fossil fuels increased by 12 percent from 1,355 million metric tons of carbon equivalent (MMTCE) in 1990 to 1,520 in 1999. (Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel use currently account for 82 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.) During the same period, Japan’s carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel use rose by 14 percent, from 269 MMTCE to 307. In contrast, EU emissions rose over the 1990s by only 1 percent from 904 MMTCE to 913.* The European Union’s maintenance of levels of carbon dioxide emissions only slightly above that of 1990 had mainly to do with the shift away from high–carbon coal sources in both Germany (following reunification) and in the United Kingdom (as a result of natural gas made available by discoveries in the North Sea)—producing a sharp decline in carbon emissions in those two countries in the early 1990s, but not a continuing downward trend thereafter. The vast majority of EU member countries, however, had significantly increased their carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels over the period. These circumstances led to the European Union’s “bubble proposal” in the Kyoto negotiations, whereby the countries of the European Union would not be held to the Kyoto reductions on a country by country basis, but would all be contained within the EU bubble.

The dramatic increase in carbon emissions of the United States and Japan, together with the European Union’s failure thus far to get below the 1990 level of emissions (and the increasing emissions of most of its member states), tells an important story. For the Kyoto Protocol, 1990 is the “year zero.” The clock is ticking and the task of getting to the zero–year level of emissions (much less below that level) by 2012 appears ever less likely—for the United States in particular. In July 2000 the chief climate negotiator for the United States under the Clinton administration, Frank Loy, declared that the United States would have to reduce its emissions by “up to 30 percent” by 2010 in order to meet the Kyoto target. Japan and Canada are in similar circumstances.

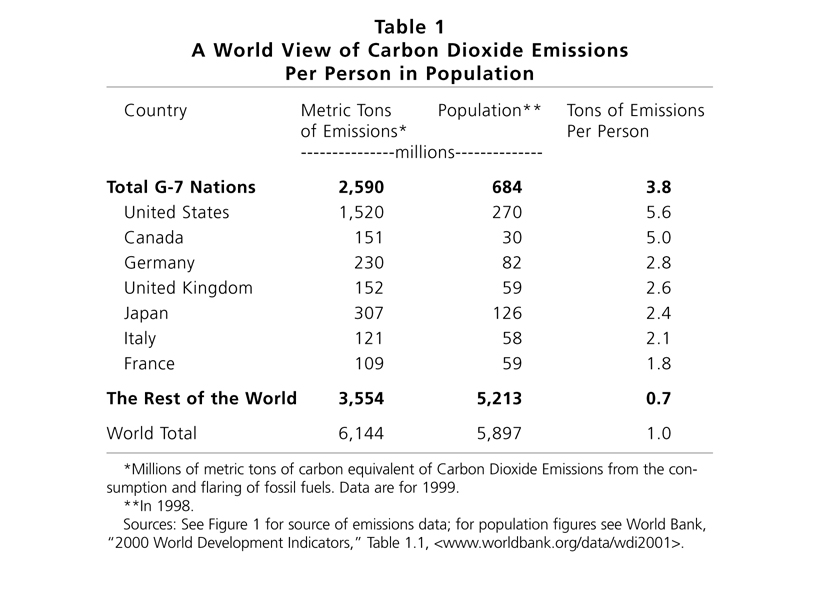

Some idea of the forces at work can be seen by looking at Table 1, showing carbon dioxide emissions per capita from the consumption of fossil fuels by various countries. The United States currently produces 5.6 tons of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel use per person per year. Germany produces half that level per capita. France, which relies heavily on nuclear energy, emits 1.8 tons per capita. Overall the leading capitalist countries (the G–7, as they were called until Russia was invited to join them as part of the G–8) emit 3.8 tons of carbon dioxide per capita per year. In comparison the entire rest of the world emits only 0.7 tons of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel use per person per year. The reasons for this large gap in the emissions between the leading industrial countries and the rest of the world is obvious. According to the World Bank, the industrial economies consume around four times as much energy per capita (measured in barrel of oil equivalent) than do the underdeveloped economies (World Development Report, 1992, p. 115).

As economic growth occurs in carbon–based capitalist economies the demand for fossil fuels rises as well. Mere increased energy efficiency—as opposed to the actual development of alternative forms of energy—is unable to do much to arrest this process in the face of increasing demand. Insofar as increased efficiency reduces unit energy costs, it tends to lead to increased demand. High demand for fossil fuel use is also encouraged by the high profits to be obtained from this, inducing capital to structure the energy economy around fossil fuels (a reality that is now deeply entrenched). In the United States the Bush administration’s push for coal–fired power plants in response to the California energy crisis, plus its withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol, played a part in the doubling of U.S. coal prices in just six months (New York Times Magazine, July 22, 2001, pp. 31–34).

The degree to which a carbon–based economy is endemic to advanced capitalism can be seen in the failure of the Clinton administration to keep carbon dioxide emissions from steadily rising; in Japan’s growing emissions over the 1990s despite the stagnation of its economy; and in the European Union’s inability to prevent most of its member states from increasing their greenhouse gas emissions. It is also evident in the Bush administration’s National Energy Policy: Report of the National Policy Development Group (headed by Vice President Dick Cheney) for 2001, which was meant to justify the administration’s call for 1,300 additional power plants to meet projected energy needs. This national energy policy advocated by the Bush administration includes only a very brief reference (six paragraphs in the middle of a lengthy report) to global warming.

In July, the Bush administration signaled its opposition to an international proposal, commissioned by the G–8, to phase out subsidies for fossil fuel while increasing subsidies for nonpolluting energy sources. The U.S. government claims such measures would interfere with the smooth operation of the marketplace, which could more adequately decide the appropriate mix of energy sources. The European Union, for its part, decided in July 2001 not to phase out its own subsidies for coal, which were previously scheduled for July 2002, but to continue these subsidies for another decade (The Economist, July 28, 2001).

The great irony behind the failure of the Kyoto Protocol is that it represented, even in its original conception, only a very modest, symbolic first step in arresting the global warming trend. Although aimed at a stabilization of greenhouse gas emissions at around 5 percent below the 1990 level, it fell far short of the massive cuts in emissions that world climate scientists have repeatedly insisted would be necessary in order to stave off global warming. According to the London Times (July 9, 2001), “Not even the treaty’s most ardent advocates contend that it is enough to contain global warming. Several models suggest that its impact by 2100 will be a temperature increase of just 0.15 °C less than would occur if nothing is done. Jerry Mahlman, of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, says another 30 similar treaties might be required to reduce greenhouse emissions by the 60 to 70 per cent that would make an appreciable difference to the climate.”

Determined to oppose emission reductions even as modest as the Kyoto Protocol, Washington, along with some of the major oil companies, has turned to exotic research in carbon sequestration technology as a long–run solution to the problem—one that would supposedly allow such emissions to increase, while protecting the environment. “We all believe technology offers great promise to significantly reduce emissions,” Bush declared in June 2001, “especially carbon capture, storage and sequestration technologies.” The U.S. government is thus putting tens of millions of dollars, through the Department of Energy, into research into such technologies. These technologies are aimed at: (1) pulling carbon dioxide out of the air; and (2) injecting it back into the coal mines and oil fields from whence it came or into the oceans.

William Nordhaus, the foremost establishment economic analyst of global warming, and his coauthor Joseph Boyer, argue, predictably, in Warming the World (2000), that “the Kyoto Protocol has no grounding in economics or environmental policy.” Nordhaus and Boyer recommend that the enormous costs to private industry, associated with a global emissions reduction regime, not be taken on too rashly, and advocate instead further research into what they call a prospective “costless” technology: “geoengineering,” which would “include injecting particles into the atmosphere to increase the backscattering of sunlight and stimulating absorption of carbon in the oceans” (p. 126–27).

All of the hoped–for carbon capture and sequestration technologies are designed to get around the emissions problem, allowing the carbon–based economy to continue as before unchanged. None of these technologies are remotely practical at present and may never be. Research ideas currently receiving government and corporate funding, discussed in Discover magazine (August 2001), involve the search for something on the order of a “giant absorbent strip, coated with any of the many chemicals that react with carbon dioxide, that could pull the gas from the air as it passes by,” coupled with fleets of ships pulling two–mile–long pipes that will pump chilled, pressurized carbon dioxide deep into the oceans. In other words, proposals are under consideration that involve a scale of operation that might well dwarf the star wars defense system, both in magnitude and sheer folly. All of them raise major environmental considerations of their own. The fact that such research is being funded and given serious consideration demonstrates that, for the advanced capitalist economies, emission reductions as a solution to global warming are much less desirable than sci–fi technological solutions that will allow us simply to reroute such waste. The solution being proposed via sequestration technology is to dump the excess carbon dioxide elsewhere—in the oceans instead of the atmosphere. The use of the ocean as the final destination for the wastes of the human economy was an issue that already concerned Rachel Carson in the 1950s and ‘60s.

From any rational perspective, greenhouse gas emission reductions on a level far more aggressive than what was envisioned by the Kyoto Protocol are now needed to address global warming. The IPCC Working Group I concluded in its 2001 report that “there is new and strong evidence that most of the warming observed over the last fifty years is attributable to human activities.” In place of the IPCC’s earlier estimate of an increase in temperature by 1.0–3.5 °C (1.8–6.3 °F) in this century, they now estimate an increase of 1.5–6.0 °C (2.7–10.8 °F). If this increase (even in the middle range) comes true, the earth’s environment will be so radically changed that cataclysmic results will undoubtedly manifest themselves worldwide. These will surely include increased desertification in arid regions and heavier rainfall and risks of floods in other regions; serious damage to crops in the tropics and eventually in temperate areas as well; rising sea levels (due to the melting of glaciers) that will submerge islands and delta regions; damage to ecosystems; and loss of both species and genetic diversity. On top of all of this, there will be increased risks to human health. As always the most exploited areas of the world and their inhabitants will prove most vulnerable.

Yet, no matter how urgent it is for life on the planet as a whole that greenhouse gas buildup in the atmosphere be stopped, the failure of the Kyoto Protocol significantly to address this problem suggests that capitalism is unable to reverse course—that is, to move from a structure of industry and accumulation that has proven to be in the long run (and in many respects in the short run as well) environmentally disastrous. When set against the get–rich–quick imperatives of capital accumulation, the biosphere scarcely weighs in the balance. The emphasis on profits to be obtained from fossil fuel consumption and from a form of development geared to the auto–industrial complex largely overrides longer–term issues associated with global warming—even if this threatens, within just a few generations, the planet itself.

The Gods of Profit vs. the Environment

“The modern world,” Rachel Carson observed in 1963, “worships the gods of speed and quantity, and of the quick and easy profit, and out of this idolatry monstrous evils have arisen.” The reduction of nature to factory–like forms of organization in the interest of rapid economic returns, she argued, lies behind our worst ecological problems (Lost Woods, pp. 194–95). Such realities are, however, denied by the vested interests who continue to argue that it is possible to continue as before only on a larger scale, with economics (narrowly conceived) rather than ecology having the last word on the environment in which we live. The depth of the ecological and social crisis of contemporary civilization, the need for a radical reorganization of production in order to create a more sustainable and just world, is invariably downplayed by the ruling elements of society, who regularly portray those convinced of the necessity of meaningful ecological and social change as so many “Cassandras” who are blind to the real improvements in the quality of life that everywhere surround us. Industry too fosters such an attitude of complacency, while at the same time assiduously advertising itself as socially responsible and environmentally benign. Science, which all too often is prey to corporate influence, is frequently turned against its own precepts and used to defend the indefensible—for example, through risk management analysis.

It was in defiance of such distortions within the reigning ideology, reaching down into science itself, that Rachel Carson felt compelled to ask, in her 1962 Women’s National Press Club speech:

Is industry becoming a screen through which facts must be filtered, so that the hard, uncomfortable truths are kept back and only the harmless morsels allowed to filter through? I know that many thoughtful scientists are deeply disturbed that their organizations are becoming fronts for industry. More than one scientist has raised a disturbing question—whether a spirit of lysenkoism may be developing in America today—the philosophy that perverted and destroyed the science of genetics in Russia and even infiltrated all of that nation’s agricultural sciences. But here the tailoring, the screening of basic truth, is done, not to suit a party line, but to accommodate to the short–term gain, to serve the gods of profit and production (Lost Woods, p. 210).

We are constantly invited by those dutifully serving “the gods of profit and production” to turn our attention elsewhere, to downgrade our concerns, and to view the very economic system that has caused the present global degradation of the environment as the solution to the problems it has generated. Hence, to write realistically about the conflict between ecology and capitalism requires, at the present time, a form of intellectual resistance—a ruthless critique of the existing mode of production and the ideology used to support its environmental depredations. We are faced with a stark choice: either reject “the gods of profit” as holding out the solution to our ecological problems, and look instead to a more harmonious coevolution of nature and human society, as an essential element in building a more just and egalitarian social order—or face the natural consequences, an ecological and social crisis that will rapidly spin out of control, with irreversible and devastating consequences for human beings and for those numerous other species with which we are linked.

* Figures exclude Luxemburg.

Comments are closed.