Richard Levins wrote in these pages (July–August 1986) that an appreciation of history and science is necessary to understand the world, challenge bourgeois ideological monopoly, and transcend religious obscurantism. Knowledge of science and history is needed in order not only to comprehend how the world came to be, but also to understand how the world can be changed. Marx and Engels remained committed students of the natural sciences throughout their lives, filling notebooks with detailed comments, quotes, and analyses of the scientific work of their time. Marx, through his studies of Greek natural philosophy—in particular Epicurus—and the development of the natural sciences, arrived at a materialist conception of nature to which his materialist conception of history was organically and inextricably linked. Marx and Engels, however, rejected mechanical materialism and reductionism, insisting on the necessity of a dialectical analysis of the world. Engels’s Dialectics of Nature serves as an early, unfinished attempt to push this project forward. A materialist dialectic recognizes that humans and nature exist in a coevolutionary relationship. Human beings are conditioned by their historical, structural environment; yet they are also able to affect that environment and their own relationship to it through conscious human intervention.

As John Bellamy Foster explains in Marx’s Ecology, the materialist basis of Marx’s approach to understanding the interconnection of nature and society, including an approach to the material world and its transformations, was preserved and even advanced by some Marxist intellectuals in the natural sciences at the same time that Marxian social science was already retreating from a materialist conception of the physical world, rejecting any connection between nature and dialectics, historical materialism and nature. Within Western Marxism materialism was increasingly emptied of any relation to nature and was reduced to practical materialism (the transformative actions of humans in the production of social life), particularly in relation to the economic conditions underpinning human society. Yet for a brief period in the 1920s and early ’30s, a materialist and dialectical approach (if sometimes marred by the intrusion of mechanistic assumptions) was the intellectual foundation for many prominent Soviet scientists, such as V. I. Vernadsky, N. I. Vavilov, and Alexander Oparin, in their various research projects regarding the creation of the biosphere, the original centers of the agricultural world, and the emergence of life. All of this subsided, however, with the tightening grip of Stalinism in the 1930s. A more rigidly mechanistic approach became dominant in Soviet science (seizing the name of “dialectical materialism” while vacating it of any meaning), putting an end to the early stages of a hopeful and exciting investigation.*

Fortunately, a generation of British scientists in the 1930s embedded in the elite universities—inspired by both Darwin and Marx and influenced by their contemporaries within Soviet science—were committed to an historical materialist and dialectical philosophy. These British scientists—Hyman Levy, Lancelot Hogben, J. D. Bernal, Joseph Needham, J. B. S. Haldane, and historian/philosopher of science Benjamin Farrington—struggled to retain within the emerging natural sciences the possibility of dialectical uncertainty, and within the ecological sciences a materialism that yet allowed for human action. Much of their work served as a critique of and challenge to the renewed idealism in the form of a vitalism that (while godless) was immersed in notions of a predetermined direction in natural and social evolution. While change was part of this vitalistic holism, the unfolding of the universe was seen by many as being guided by an inner purpose or teleology. Bourgeois ideology, with its opposite poles of vitalism and mechanism, sought to justify existing social hierarchies, in terms of domination that was biologically derived and teleologically predetermined—whether in terms of racism, sexism, or some other form. The Marxist scientists in Britain fought against these distorted developments, and particularly against vitalistic views, advancing an approach that combined materialism with dialectics, scientific critique with radical worker education. Their focus on the dialectics of nature, though undeveloped and still at times insufficiently dialectical, was thus not a strange, deviant tangent of science as often alleged. It was central to many of the major scientific discoveries of the time and a source of critique of social dogmas.

Growing out of the work of these early critical intellectuals, a more developed, non-teleological science grounded in materialist dialectics came to the fore in the 1960s and 1970s with the work of Marxist-influenced scientists—particularly Richard Lewontin, Richard Levins, and Stephen Jay Gould at Harvard, then the leading center of evolutionary biology. This year marks the twentieth anniversary of Levins and Lewontin’s book, The Dialectical Biologist, one of the foremost examples of a genuinely dialectical materialist approach to history and science. Levins and Lewontin discuss a wide range of subjects including evolution, scientific analysis, science as a social product, and the products of science. Their discussions of these issues present a challenge to received thought with its naturalistic explanation of social conditions. Levins and Lewontin describe how mainstream science typically assumes evolution to be a progressive process leading to a state of equilibrium. Within this dominant view, an ideology of biological determinism is used to justify inequalities, arguing that differences in abilities among humans are innate and that these innate differences are biologically inherited. Additionally, Lewontin notes, it is too often assumed that it is human nature to confer more rewards and status to those with “better” abilities and the “right kinds of genes” (Biology as Ideology, 10–23). Such mechanistic, reductionist science is perfectly suited to the ruling-class ideology. At the genetic level life is reduced to independent, individual actors (so-called “selfish genes”), which carry out a Hobbesian struggle of all against all, thereby inscribing most natural and social characteristics within DNA. Likewise at the species level, constraints are seen as being placed on species that must either adapt to their environments or perish. A rigid natural order is presumed to exist in this doubly ahistorical universe that narrowly delimits the roles played by living things, including human beings, in their own evolution, and in the evolution of their natural environments.

In The Dialectical Biologist, Levins and Lewontin reject one-sided notions of mechanical reductionism and superorganic holism (common in ecology) and the hierarchical conceptions of life and the universe that they both generate. In presenting their approach, they critique both idealism and reductionism within the natural sciences. Instead Levins and Lewontin argue for a dialectical and materialist approach that understands that the world “is constantly in motion. Constants become variables, causes become effects, and systems develop, destroying the conditions that gave rise to them” (279). The universe is one of change due to existing and evolving contradictions, which force transformation in the conditions of the world. “Things change because of the actions of opposing forces on them, and things are the way they are because of the temporary balance of opposing forces” (280).

A dialectical relationship exists between a subject, such as an organism, or even human society, and the environment. They exist as one (in tension), given that an organism is part of nature. The former is dependent upon the latter for its existence, and both realms are transformed throughout their relationship, but “do not completely determine each other” (136). Darwin downplayed (but did not deny) the importance of the constraints placed on evolutionary change due to the structured nature of the ontogeny (individual development) of organisms, which potentially restricts the types of changes organisms can undergo in their phylogeny (evolutionary history). He elevated the conditions of existence—external environmental forces—to primacy in explaining evolution, so as to establish natural selection, not the final ends of natural theology, as the dominant force behind the transformation of species. Yet in so doing, he established a view of natural history as predominantly one-sided—i.e., the environment was seen as largely determining the evolutionary process, and not as equally the consequence of the evolution of life. Darwin recognized that variation is an internal process, in which causes external to organisms did not determine how things turned out. However, he generally assumed that any pattern to variation was of subsidiary importance for evolution. In order to grapple fully with the evolution of life and the transformations of the world, Levins and Lewontin stress, it is necessary to consider the complex interactions of both the internal and external dimensions of life.

Whereas the ultra-Darwinian view of evolution focuses nearly exclusively on the external (while Darwin himself was somewhat more pluralistic), modern geneticists analyzing the developmental processes of individual organisms (ontogeny) often focus nearly exclusively on the internal in their acceptance of genetic determinism. Counter to this genetic determinism (and narrow reductionism), Levins and Lewontin, in The Dialectical Biologist, explain,

An organism does not compute itself from its DNA. The organism is the consequence of a historical process that goes on from the moment of conception until the moment of death; at every moment gene, environment, chance, and the organism as a whole are all participating….Natural selection is not a consequence of how well the organism solves a set of fixed problems posed by the environment; on the contrary, the environment and the organism actively codetermine each other. (89)

At the center of Levins and Lewontin’s analysis is a focus on interaction, transformation, and historical constraints. Life is not simply a free-flowing, hodgepodge series of independent events. Instead, it emerges from the complex interactions that are constantly taking place. They explain (89–106) that an organism is both a subject and object, and a dialectical analysis is necessary to understand the interaction between organisms and the environment. In day to day operations, any number of materials (rocks, water, etc.) may exist in the environment, but organisms interact and utilize a small portion of what is available; thus in their patterns of life they determine what is relevant to their development. In the process of obtaining sustenance, organisms must interact with their environment, and in so doing they transform the external world—both for themselves and other species. Their consumption of parts of the external world is also the production of new environments. Of course, it is recognized that the conditions of the environment are not wholly of their own choosing, given that there are natural processes independent of a particular species. Previously living agents have historically shaped nature, and coexisting species are also engaged in altering material conditions. Organisms convert the physical signals and information from the external environment into information that causes physical transformations in the organisms themselves. The biology of a species will determine if and what information is received. Ultraviolet light helps lead bees to food; for humans it can cause skin cancer. The value and use of existing information varies among species. The “traits” selected are determined by the dynamic organism-environment relationship. “Neither trait nor environment exists independently,” thus what becomes useful is a consequence of a long historical process—one that is subject to change. An organism is the result of complex interactions between its genes and environment, where the organism takes part in the creation of its environment and its own construction. In this, it sets—in part—the conditions of its natural selection, by being both the object and subject.

In the current era, biological reductionism dominates many discussions of the structure of life. In The Triple Helix, Lewontin challenges such simplistic accounts of the world and extends his dialectical analysis, noting that while genetic differences can serve as an explanation for why lions look different from lambs, they are not sufficient for explaining “why two lambs are different from one another.” In fact, genes may be irrelevant for some characteristics. Rather than assuming that the gene determines the course of development, Lewontin explains “that the ontogeny of an organism is the consequence of a unique interaction between the genes it carries, the temporal sequence of external environments through which it passes during its life, and random events of molecular interactions within individual cells. It is these interactions that must be incorporated into any proper account of how an organism is formed” (17–18). The organism is a site of interaction between the environment and genes. Specific historical forces influence the conditions of an organism’s emergence. A dialectical influence is constantly associated with changes throughout life. Lewontin emphasizes that while “internally fixed successive developmental stages are a common feature of development, they are not universal” (18). For example, the morphology of the tropical vine Syngonium varies depending upon incidences of light conditions. The shapes of its leaves, as well as their spacing, change along with environmental conditions. In short, organisms do not develop independent of their environmental context.

In The Triple Helix, Lewontin dismantles genetic determinism and the associated assumption of predictability, by illustrating how complex interactions lead to variation at all levels. He discusses experiments on clones of different genetic strains of the plant Achillea, where each strain was grown at different elevations to test inherent characteristics of the plants. The findings indicate that it is not possible to predict “the growth order from one environment to another” (22). The plants (within genetic groups) vary in growth between environments (material contexts), without any predictable pattern. For example, at one elevation one strain would be taller than the other strains, but at another elevation it may be shorter. Even the norm of reaction, “a pattern of different developmental outcomes in different environments,” for the various plants is comprised of “complex patterns that cross each other in unpredictable ways,” preventing reliable correlation in growth from one setting to another (23–24). The specific characteristics of an organism will vary, depending on the environments (historical specificity) in which it is immersed (28–30). Thus, we must take into account the history of living organisms (including their environments and their structure) in order to gain an understanding of their situation.

Stephen Jay Gould, perhaps the most widely recognized recent evolutionary theorist, was strongly influenced by Levins and Lewontin, and was, in his own right, a key figure in developing a dialectal view of the evolutionary process. Among his many contributions is an elegant theorization of how the dialectical interaction between the internal structural constraints of organisms—stemming from what have traditionally been referred to as “laws of form”—and the external pressures of the environment (natural selection) generate the patterns of observed evolutionary change. His most comprehensive treatment of this issue can be found in his magnum opus, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, published in 2002, shortly before his untimely death. He argued that organisms are not mere putty to be sculpted over the course of their phylogeny by external environmental forces, but, rather, their structural integrity constrains and channels the variation on which natural selection operates. In other words, the Darwinian assumption that variation is effectively without pattern is incorrect. Therefore, the evolutionary process is a dialectical interaction between the internal and the external, in much the same way as the ontogeny of individual organisms is a dialectical interaction between their genes and the environment (as argued by Lewontin in The Triple Helix).

Gould’s emphasis on recognizing the important role structural forces play in evolution arises out of a critique of the hyper-functionalism and extreme reductionism of ultra-Darwinians who identify all traits of organisms as adaptations. Gould and Lewontin in a famous paper published in 1979 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme,” identify the functionalist ultra-Darwinian view as the “Panglossian Paradigm.” The Panglossian Paradigm is named for Voltaire’s character in his novel Candide, Doctor Pangloss (a satirical representation of Gottfried Leibniz), who responded to all misfortunes by saying, “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” Gould and Lewontin argued that ultra-Darwinians had come to rely overly on “just so” stories for explaining any and all characteristics of organisms, constructing tales of how each and every trait served some function, regardless of whether sufficient evidence existed to support these claims.

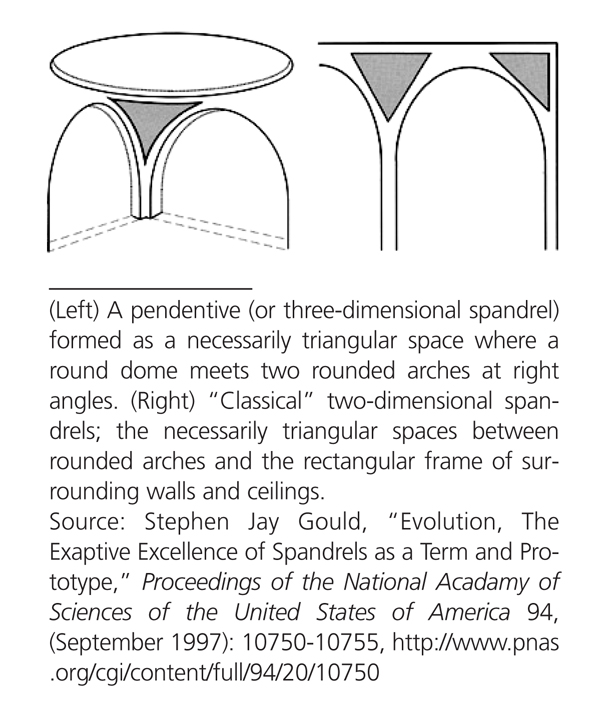

Contrary to this functionalist approach, Gould and Lewontin posited that some characteristics of organisms are merely side consequences of structural forces, and not necessarily adaptive. They illustrate their argument using an architectural analogy (see illustration). They note that construction of a dome on rounded arches requires the construction of four spandrels (the architectural term for spaces left over between structural elements of a building), which set the “quad-ripartite symmetry of the dome above” (582). The spandrels are, therefore, a necessary side consequence of the structural demand for a dome on rounded arches, but serve no function in themselves. Similarly, the structural nature of ontogenetic development of organisms typically leads to the existence of nonadaptive structural elements (spandrels). For example, as Gould explains in The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, “snails that grow by coiling a tube around an axis must generate a cylindrical space, called an umbilicus, along the axis” (1259). Although a “few species use the open umbilicus as a brooding chamber to protect their eggs” (1259), the vast majority do not. Evidence suggests that “umbilical brooders occupy only a few tips on distinct and late-arising twigs of the cladogram [evolutionary tree of coiling snails], not a central position near the root of the tree” (1260). Therefore, it appears clear that the umbilicus did not arise for adaptive reasons, although it was later co-opted for adaptive utility in a handful of lineages, but, rather, arose as a nonadaptive spandrel—a side consequence of a growth process based on coiling a tube around an axis. A key lesson to be drawn from Gould and Lewontin’s argument, then, is that functionalist explanations are not sufficient to capture the plurality of forces operating in the natural world.

As Lewontin, Levins, and Gould explain, evolution is not an unfolding process with predictable outcomes, but a contingent, wandering pathway through a material world of constraints and possibilities. In The Dialectical Biologist Levins and Lewontin contend that the larger, physical world in which an organism is situated is filled with its own contingent history and structural conditions—i.e. caught up in what might be described as historical processes (286–288). Interactions (the collisions of atoms, as Epicurus wrote) are part of the fabric of life, because objects throughout the physical world are interconnected. Multiple pathways or channels exist, in relation to the structural integrity of organisms, for evolutionary processes—in fact, they are part of what created life and makes its continuance possible. Even when the external conditions are fixed, multiple pathways exist, as life creates its own path, in its interactions with opposing forces. Emergence is an outgrowth of life, given the active existence of its heterogeneous organization. The constant interactions and interpenetration of opposites, at all levels of existence, provide the means for the mutability of life, making contingency a force in both the natural and social universe. The dialectical interchange between the environment and the organism is a central tenet of the coevolutionary position. Both the environment and organism are integrated levels, “partly autonomous and reciprocally interacting,” in both directions (288). Change is the rule of life. Organic processes are historically contingent, defying universal explanations. Thus, both the parameters of change and the nature of transformation are subject to change given the ongoing development of life (277). Both the phylogenic emergence and ontogenic development of an organism involve internal and external dynamics. So long as genes, organisms, and environments are studied separately, our knowledge of the living world will not advance. Levins and Lewontin help us overcome this problem by providing the basis for breaking the myopic, reductionistic vision of bourgeois science, allowing us to gain a rich understanding of nature and its dynamic processes, and affirming that science should be and needs to be used to educate and empower the public to address the various problems that confront society, including its unsustainable interaction with nature.

A genuinely dialectical materialist position is fruitful for understanding the dynamic relationships that exist in nature and the evolutionary process of life. While social history cannot be reduced to natural history, it is a part of it. A dialectical stance is essential in order to understand the material world in terms of its own becoming: recognizing that history is open, contingent, and contradictory. In a time when ruling-class ideology permeates every pore of the social world and genetic explanations reign as justifications for social differences and inequalities, the work of Lewontin, Levins, and Gould liberates scientific research and social knowledge from the social constructs of “bad science.” Materialist dialectics have been resolutely preserved within certain traditions in natural science, as well as specific Marxian schools of thought, such as the one represented by this magazine. A dialectical and materialist approach becomes essential for human society, given the scale of environmental degradation in our contemporary world and the fact that there is no evidence that organisms are becoming more adapted to the environment. Evolution does not entail a drive towards perfection, nor is there a perfect state of balance in existence (much less waiting to be discovered). Keeping things as they are is not an option, because change is a constant. But we must try to gain as much knowledge as we can regarding the conditions and processes of the world, so we can try to affect the course of change, to whatever degree is possible given historical constraints and conditions, in order to make a decent world possible for all life. The extent to which we succeed as social agents will determine the longevity of social history in the making, our relation to the natural world, and the potential for revolutionary change.

Notes

* The term “dialectical materialism” is often used derisively within contemporary Western Marxism and has come to symbolize Stalinist dogma. Our intention here is to rehabilitate the term by using it to refer exclusively to those inquiries that can be seen as genuine attempts to employ dialectical and materialist methodologies in both the natural and social realms. Materialism without dialectics tends toward mechanism and reductionism. Dialectics without materialism tends toward idealism and vitalism. Genuine dialectical materialism seeks to transcend these antimonies. It thus stands for a critical realism sorely lacking in conventional thought.

Comments are closed.