The United States and the Colombian ruling oligarchy have, since the 1960s, repeatedly implemented socioeconomic and military campaigns to defeat the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia–Ejército del Pueblo, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (FARC–EP). However, this offensive, whose main purpose is to maintain capitalist accumulation and expansion, has resulted in an embarrassing setback for U.S. imperialism and the Colombian ruling class. In a time of growing and deepening U.S. imperialism, it is important to examine this failure. Over the past four decades, despite U.S. efforts, support has risen for what has been the most important continuous military and political force in South America opposing imperialism. I examine how the FARC–EP has not only maintained a substantial presence within the majority of the country but has responded aggressively to the continuing counterinsurgency campaign. I also show as false the propaganda campaign of the U.S. and Colombian governments claiming that the FARC–EP is being defeated. This analysis provides an example of how a contemporary organic, class-based sociopolitical movement can effectively contend with imperial power in a time of global counterrevolution.

Some Historical Background

Many years ago, Che Guevara drove through Colombia and wrote in his Motorcycle Diaries (Ocean Press, 2004, 157) that the so-called oldest democracy in Latin America had “more repression of individual freedom” than any other country he had visited. Since Che’s journey, little has changed.

During the mid-twentieth century Colombia was to experience several firsts in Latin American. Colombia was the first state to receive assistance from the World Bank (then called the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development). It was also the first country to receive official counterinsurgency and military assistance from the United States. During the decade of the 1960s the percentage of the national budget allocated for military expenditure, for the purpose of combating peasant and guerrilla forces, was over 16 percent.

In the current period Colombia finds itself in the throes of civil war, embedded in a model of neoliberal economics and overall subordination to the United States. A small group of very wealthy landowners and capitalists within the country have the ability directly to affect governmental policy and economic conditions. Polarization of wealth is extreme. The richest 3 percent now own over 70 percent of the arable land, while 57 percent subsist on less than 3 percent of that land. The richest 1 percent of the population controls 45 percent of the wealth, while half of the farmland is held by thirty-seven large landholders.1

The current president, Álvaro Uribe Vélez, has sought to implement a neoliberal model throughout Colombia by way of mass privatization, the removal of tariffs, and restricting labor unions. Uribe has supported measures that have reduced overtime wages, raised the age of retirement by a third, and cut the salaries of public sector workers by 33 percent. After neoliberal restructuring the disproportion in wealth yet further increased. In 1990, the ratio of income between the poorest and richest 10 percent was 40:1. By 2000 the ratio reached 80:1.2 This economic reality underlies all political and legal events in Colombia. All hypocritical blather about democracy and the rule of law aside, the Colombian state is ruled with great brutality by what Venezuela’s Chávez has termed a “rancid oligarchy,” supported of course by the United States.

In the face of this reality, Colombia has maintained a strong tradition of leftist opposition. In an 1872 essay, “The Possibility of Nonviolent Revolution,” Marx suggested that some countries may contain a proletariat that “can attain their goal by peaceful means” however, he asserted, “we must also recognize the fact that in most countries” this is not the case and that “the lever of our revolution must be force.” If this be true of any country in the world today, that country is Colombia.

Class consciousness in Colombia has again and again constructed itself organically in the face of its ruling class. In the late 1930s through the 1950s several hundred rural-based Colombians, of communist ideology, organized themselves into structures of cooperation and security in response to expanding capitalist interests penetrating the hinterland. State-induced repression and violence aimed at small landholders, peasants, rural workers, and other semi-proletarians met a peaceful, but firm (and armed), response. Trying to exist as an autonomous geographical community, these “self-defense groups” were based on nuclei of peasants operating land collectively in relatively isolated regions of the country. They sought to establish a stable society, uncorrupted, and based on local control, and to counter the repressive central government by extending the communities into other areas. With support from a significant minority of the rural population, these localized self-defense groups progressively expanded their spheres of influence in the late 1950s and early 1960s to include multiple areas of southern and central Colombia. By 1964, over sixteen such groups of communities had been successfully established throughout the country. The communities, although peaceful, were considered a tremendous threat to not only the large landowning class and rising urban capitalists but also to the United States’ geopolitical interests. As a result, these regions became military targets during the Cold War offensive in Latin America that intensified under the Kennedy administration.3

In May of 1964, the United States and the Colombian government agreed to carry out attacks against the rural collectives, with ground zero being the Marquetalia region in the department of Tolima in southwestern Colombia. The military assault, commencing May 27, 1964, was made possible by extensive economic and military support from the United States through the Latin American Security Operation Plan. As a result, the FARC–EP considers May 27, 1964, the official date of its origin. Contrary to the reports of several scholars that the FARC–EP had been liquidated; the organization not only maintained its existence but consistently expanded throughout the country.

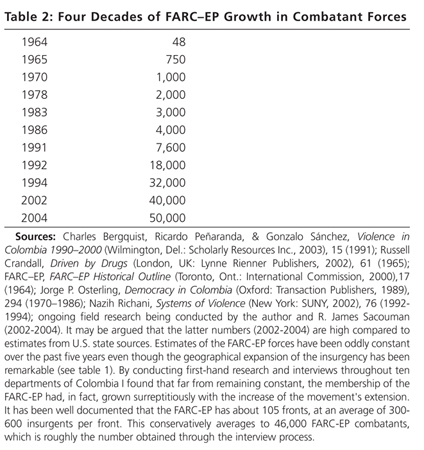

The FARC–EP—pursuant to Protocols I and II of the Geneva Conventions, which stipulate that oppositional armed movements vying for state power must formally arrange themselves into a visible ranked military construct—is formally organized as an Ejército del Pueblo (a people’s army) with a distinct chain of command. The Secretariat of the Central General Staff consists of seven members (Manual Marulanda Vélez, Raúl Reyes, Timoleón Jiménez, Iván Márquez, Jorge Briceño, Alfonso Cano, and Iván Ríos), who oversee the Central General Staff composed of twenty-five members specifically located within seven blocks throughout the country (Eastern, Western, Southern, Central, Middle Magdalena, Caribbean, and Cesar). In each of these blocks there are a number of fronts that contain, on average, 300 to 600 combatants per unit. By 2002, it was generally conceded that 105 fronts exist throughout the country. Figures obtained by the author through participant observation and open-ended interviews with the FARC–EP establish that there are at least an additional dozen fronts. Today the number of regions in Colombia with a significant FARC–EP presence is substantial; however, very little analysis of this topic has been collected, examined, or presented to the larger public.

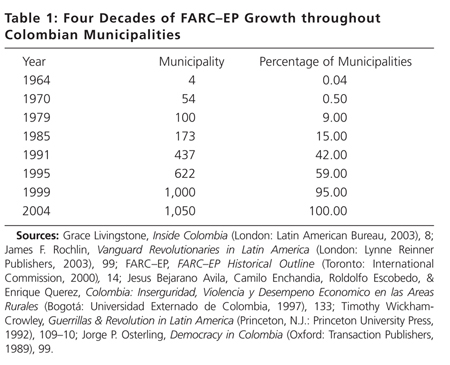

Immediately after its founding, the insurgency was active in four municipalities and expanded its influence during the 1970s and 1980s. It was during the 1990s—with the rise of neoliberal economic policies accompanied by increased state repression, often carried out with unspeakable brutality by government-sanctioned paramilitaries—that the FARC–EP dramatically increased its social presence throughout the country. A comprehensive study published in 1997 revealed that the insurgency had tangible influence in 622 municipalities (out of a total 1,050).4 In 1999, the FARC–EP had increased its power to more than 60 percent of the country, and in less than three years it was estimated that over 93 percent of all “regions of recent settlement” in Colombia had a guerrilla presence.5 One example is the department of Cundinamarca, which completely surrounds the capital city of Bogotá. Within this area the power of the FARC–EP extends throughout 83 of the department’s 116 municipalities. Although its power varies in each borough, there is good reason to believe that the FARC–EP is present in every municipality throughout Colombia. Some areas are formally arranged by the FARC–EP with schools, medical facilities, grassroots judicial structures, and so on, while others may have a guerrilla presence albeit in a much smaller capacity. In conjunction with the material rise of the FARC–EP it cannot be denied that the insurgency has considerable support from the civilian population. Over the past several years, an increasing number of rural inhabitants have begun to migrate to FARC–EP inhabited regions, be it for protection or solidarity. During peace negotiations between the insurgency and the Colombian government (1998–2002), over 20,000 people migrated to the FARC–EP held Villa Nueva Colombia in one year alone. Many preferred to live in the rebel safe haven since it provided a sense of security and the ability to create alternative community-based development projects.6 No better example of the growing support for the FARC–EP exists than the number of rural inhabitants entering the FARC–EP maintained demilitarized zone (DMZ), acquired by the insurgency during the peace talks. The DMZ, prior to (official) FARC–EP consolidation, had a population of only about 100,000 inhabitants.7 By the time the Colombian government invaded the region and ended the peace negotiations there were roughly 740,000 Colombians who had migrated to the guerrilla held territory.8

Throughout the four decades since its inception, the FARC–EP has developed into a complex and organized movement (see Table 1). Its program addresses a range of critical political, social, cultural, and economic issues. Based upon ongoing research conducted by the author, the current constituency of the organization has grown from its base in the subsistence peasantry to incorporate indigenous populations, Afro-Colombians, the displaced, landless rural laborers, intellectuals, unionists, teachers, and sectors of the urban workforce. Forty-five percent of its members and commandantes are women. What began as a largely peasant-led rural-based land struggle in the 1960s has since been transformed into a national sociopolitical movement attempting alternative development objectives through the realization of a socialist society. By constructing a substantial support base, extensive geographical distribution, and an expanding ideological model of emancipation, the FARC–EP has, with the exception of Cuba, become the largest and most powerful revolutionary force—politically and militarily—within the Western Hemisphere.

The FARC–EP, unlike many recent revolutionary movements and struggles in Central and South America, is a peasant-based, organized, and maintained revolutionary organization. The revolutionaries were not formed within classrooms or churches; they are not a movement led or largely made up of lawyers, students, doctors, or priests. On the contrary, the FARC–EP’s leadership, support-base, and membership has come from the very soil from which it provides its subsistence, for the insurgents have been largely made up of peasants from rural Colombia, who account for roughly 65 percent of its members. This is important to understand when discussing the contemporary forces arrayed against it.

The Imperial Necessity of Counterinsurgency

To respond to their systemic failure in trying to defeat the FARC–EP since 1964, the political administrations of the United States and Colombia have recently reformulated their counterinsurgency plans. Part of the reason for this is that the previous drive, Clinton’s Plan Colombia, failed. Plan Colombia reinforced the Colombian military’s dominance over the country’s civil administration, through the massive infusion of U.S. money and personnel. U.S. aid to Colombia in 1995 was $30 million. Under Plan Colombia, the United States gave 2.04 billion dollars between 1999 and 2002, 81 percent for arms.9 This plan was promoted as a way to reduce cocaine availability and usage in the United States. Embarrassingly, it neither stopped the flow of cocaine to consuming countries, nor did it provide Colombia’s peasants with an alternative to cultivating the illicit crop. In the spring of 2005, it was recognized that the level of coca being cultivated within Colombia had in fact increased.

Prior to U.S. direct intervention within Colombia by way of Plan Colombia, levels of coca cultivation consistently hovered at 40,000–50,000 hectares (1986–1996). With Plan Colombia, coca levels dramatically increased. During the peak of Plan Colombia (2001) levels reached a historic high of 169,800 hectares. While a slight decline was witnessed in 2002–2003, current estimates suggest that coca cultivation is again on the increase. In fact, what has occurred in Colombia’s narco-industry is a partial monopolization of coca processing, production, internal domestic distribution, and international trafficking by the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC)—the principal paramilitary organization. The AUC openly admitted that it principally financed its counterinsurgency troops through the Colombian narcotic industry. Roughly 80 percent of paramilitary funding comes from drug trafficking.10 The reality of Clinton’s Plan Colombia is that the paramilitary forces—indirectly trained by the United States and supported by the Colombian army—now control the drug industry. The FARC–EP, often accused by U.S. propaganda of “narcotrafficking,” is merely involved in taxing revenededoras, those who purchase the leaves from the peasants.11 At most some 2.5 precent of all coca cultivation in the country is indirectly connected to the FARC–EP.12 Though the façade of a war on drugs was somewhat useful for a time, the U.S./Colombian counterinsurgency was weakened as the falsehood became evident. Therefore the aligned governments of Bush and Uribe moved toward an armed campaign against the insurgency’s support base in the people under a new rubric, the “war on terror.”

When Plan Colombia was first presented, a surprising amount of opposition arose against the Clinton administration’s plan. As a result of this pressure, the government agreed to limit the number of U.S. troops and privately-contracted forces allowed to enter Colombian territory to 800 (400 U.S. personnel and 400 contracted personnel). Under George W. Bush, a self-proclaimed war president, the Department of Defense ended these limits on U.S. participation and began a direct offensive campaign of armed aggression against specific regions of Colombia. This ongoing initiative is called Plan Patriota.

Plan Patriota has seen an enormous increase in the participation of U.S. troops and private-sector forces in armed combat in Colombia. Assaults have been carried out by conjoined United States military and private combatants, leading over 20,000 Colombian soldiers in a scorched earth policy directed at the civilian population. The plan is largely concentrated in the southern Colombian departments of Putumayo, Caquetá, Nariño, and Meta.

The reformulated policy, largely dispensing with the hypocritical “drug war” rationale, is a product of the Bush administration’s exploitation of the attacks of September 11, 2001, for openly imperial goals. Labeling Marxist revolutionary movements as “terrorist” renders the term meaningless, but it helps repress domestic opposition to U.S. global military intervention. Under the new official U.S. doctrine the terrorist label supposedly permits an assault by the U.S. military machine (in total violation of all existing international law), therefore half or more of Colombia is now subject to total war against the peasant population.

Plan Patriota was presented by the Colombian military as a prelude to the renewal of the previous government’s negotiations with the FARC–EP, which they had sabotaged. General Reinaldo Castellanos said: “our activity and the force with which it must be carried out has to compel (the rebels) to sit down under the conditions set out by the government.”13 Rural inhabitants have told me in interviews that the general has encouraged his troops to conduct murderous attacks against unarmed civilians, peasants, and supposed insurgent supporters. Under these circumstances, talk of negotiation to resolve the conflict is meaningless. The U.S. military made no such pretense. In October 2002 reports were leaked indicating that United States Marines were on “orders to eliminate all high officers of the FARC,” “scattering those who escape to the remote corners of the Amazon.”14

The United States and the Colombian government have tried to create an image that their new methods of war are working. Repeated claims have been made that the Colombian army is “winning” and driving deep into FARC–EP strongholds. In a typical article unnamed “U.S. officials” are quoted as claiming that the FARC–EP “has been significantly degraded” and now “there is no portion of the country where Colombian forces cannot go.” The piece argues that in the past “there were huge swathes of land that FARC dominated. The government could not exercise sovereignty in those places, and the FARC was free to plan further operations and train recruits in these areas” but “now the Marxist group cannot use these areas as havens, recruiting grounds or launch points for operations.” This past April, United States Air Force General Richard B. Myers claimed that the current counterinsurgency campaign being carried out in Colombia was defeating the FARC–EP. Myers was quoted saying that “we’re winning” and that “the cooperation between the United States and Colombia must be mirrored around the world” for “the future rests on the ability of nations to cooperate and concentrate against extremists.” But it is now clear that Plan Patriota has, in fact, failed utterly to defeat the FARC–EP.15

Despite propaganda that Plan Patriota was aimed at fighting the FARC–EP, what is really happening is an attempt to “drain the sea.” The target is the unarmed peasantry, due to the fact that the FARC–EP’s military capacity, power, and support largely stems from this group. Plan Patriota offenses have been carried out against “suspected rebel-extended regions.” During the early stages of Plan Patriota, James Hill, the former general of the U.S. Southern Command, admitted that the reformulated campaign began “with an attack on rural areas where local peasant farmers support the FARC,” not against the guerrilla army itself.16 In response to this brutal tactic, the FARC–EP purposely began to dissolve into the mountains and was able to take pressure off specific regions where they have received peasant and indigenous support. But the U.S. and Colombian troops attacking the peasants in fact built support for the FARC–EP and were vulnerable to ambush and counterattack.

The relationship between the peasantry and the FARC–EP has remained consistent for well over half a century and is visible throughout much of rural Colombia. During the beginning of Plan Patriota, however, some observable socio-geographical characteristics appeared to change concerning the FARC–EP alliances with the rural peasantry. One example of this was documented while I was conducting research within the department of Huila. I noted that there was minimal insurgent visibility in areas where the guerrillas had a strong presence for over seven years. In times past it was customary to be stopped at FARC–EP checkpoints on primary and secondary roads or to see guerrilla members in conversation with persons of the community. Upon discussion with people from the community and through a subsequent interview with Raúl Reyes, commandante of the FARC–EP’s International Commission, I was told that the guerrillas that have remained in the area have reduced their visible presence to prevent state aggression against the local populace. Reyes explained that the FARC–EP was trying to limit the opportunity for the U.S./Colombian state forces to enter into campesino-inhabited regions that are supporters of the insurgency. The Colombian military has a horrendous record of committing human rights abuses against noncombatants, and for this reason, the FARC–EP, during specific periods of 2003 and 2004, chose to limit its immediate visible presence in the hope of diminishing the chance of injury against the rural populations within FARC–EP extended regions. But this withdrawal was purely tactical and as events have developed the insurgency has not been marginalized by Plan Patriota but, on the contrary, has increased.

The Response to Plan Patriota

While access through the border regions surrounding the departments of southern Colombia is impeded by a major effort of the military and state-supported paramilitary, internal areas are as fully held by the FARC–EP as ever and are in fact expanding. In the last two months of 2004, it was apparent that the FARC–EP had actually increased the size of its combatant forces throughout several regions, contradicting government and mainstream media reports. In just the month of December, the FARC–EP increased the size of its movement by a total of one hundred newly trained combatants within one municipality alone. During my interview with Raúl Reyes I was told, “look around, here we are. Do you see any [government] troops? Plan Patriota has not disseminated the FARC–EP. We move freely throughout the region as we have for the past several years.” However, the withdrawal into the mountains during specific periods of 2003 and 2004 is quite different from what the insurgency has done since the onset of 2005. The FARC–EP was tactically withdrawing before the U.S./Colombian military offensive but preparing the counteroffensive, and it has of late demonstrated a completely new method of dealing with Plan Patriota.

Since February 2005, the FARC–EP has proved itself to be at the top of the short list of armed sociopolitical movements fighting imperialism. The first offensives, beginning on the first two days of the month, were labeled as the “worst two-day period for the armed forces since President Álvaro Uribe took office in August 2002 promising to defeat the rebels on the battlefield.”17 The FARC–EP assaulted a major military consolidation equipped with “river gunboats, a Phantom fixed-wing gunship and helicopters.” A few days later the offensive would be labeled as “the bloodiest rebel attack in two years.”18 The Eastern Block of the FARC–EP (one of seven blocks) averaged roughly one major attack per day during the month of February alone.

Unlike past years when one confrontation would be followed by a pause of several days or more, the FARC–EP remained vigilant in their offensive. During the subsequent days the insurgency carried out smaller tactical operations until February 9, when the guerrilla forces mounted another major attack that “ambushed 41 soldiers in the jungle province of Urabá” and “killed at least 20 Colombian soldiers,” wounded several, and left eight members of the 17th Brigade unaccounted for. The attack against the 17th Brigade was then labeled as “the deadliest attack on the armed forces in years.”19 By the end of February, the Eastern Block (by itself) had eliminated over 450 counterinsurgent forces. The campaign initiated in February has continued with an ongoing series of successful attacks on the Colombian military, dramatically illustrating that the FARC–EP not only maintained their substantial existence and support base, but grew in strength despite a determined offensive by the most vicious and powerful military forces in the world (see Table 2).

Colombia’s Immediate Future and the FARC–EP’s Role

In the spring of 2004, Raúl Reyes avowed that the FARC–EP’s support was growing and that their objective of taking state power was becoming an ever closer reality. Since the spring of 2004 the insurgency has increasingly aligned its program to directly support the interests of those exploited within the rural regions of the country. The FARC–EP counteroffensive that began on February 1, 2005, demonstrates the growing depth of their strength. The dynamic of the FARC–EP’s revolutionary strategy has developed and increased.

In May 1982, the FARC formally added Ejército del Pueblo, People’s Army, to their name, hence FARC–EP. The reasoning behind this strategy was twofold. The first was that the Secretariat, through a Marxist-Leninist strategy, understood that only through the support of the people could a socialist society be created, and in turn, the FARC–EP had to “play a decisive role in winning power for the people.”20 The second reason was based on the guerrilla’s military activity. The revolutionary ideology of the insurgency was heavily entrenched in maintaining guerrilla characteristics in defensive structure and militaristic operations. However, the insurgency recognized the need to begin its historic development by expanding its operations into “an authentically offensive guerrilla movement.”21 For years the insurgents carried on their familiar tactical patterns of micro-level attacks against state/paramilitary forces without engaging the enemy in a continuous full-scale war of assault. The actions that began in the early weeks of 2005 mark an important change. While maintaining its guerrilla structure, the FARC–EP have been moving away from small-scale operations and into large-scale, continuous, direct confrontations implemented through well-orchestrated, simultaneous attacks on state forces in many parts of the country. In the last week of June 2005, FARC–EP forces carried out a major ambush of a military unit in the far southwestern province of Putamayo (“the worst death toll in a single day for the military since Uribe came to power in 2002”), and they successfully engaged with military troops in North Santander near the Venezuelan border at the other end of the country. Since July and the beginning of August, the FARC–EP have fully usurped the department of Putumayo including several areas adjoining its southwest.

The U.S.-backed Uribe regime runs a country where torture and murder by the military and the state-backed paramilitaries goes unpunished. Repeatedly Colombia has been acknowledged to be the most dangerous country in the world to be a trade unionist, with hundreds murdered in the last several years and no one yet punished. Poisoned by U.S. “anti-drug” spraying operations and assassinated by Colombian soldiers and paramilitary, the peasants have suffered greatly in the years of Clinton’s Plan Colombia and the Bush/Uribe Plan Patriota. Under these circumstances the heroic response of the FARC–EP is a testament to the human spirit. They have demonstrated not only that class-conscious support for revolution can be created in populations subjected to the utmost brutality by the forces of U.S. imperialism and the murderous Colombian oligarchy, but also that through solidarity and emancipatory fortitude successful armed revolutionary guerrilla warfare remains a viable option in contemporary geopolitics.

Notes

- Garry M. Leech, Killing Peace (New York: Information Network of the Americas, 2002), 9; Ramsey Clark, “The Future of Latin America” in War in Colombia (New York: International Action Center, 2003), 23–47.

- Doug Stokes, America’s Other War (London: Zed Books, 2005), 130.

- Ernest Feder, The Rape of the Peasantry (New York: Anchor Books, 1971), 189. James Petras & Maurice Zeitlin, Latin America: Reform of Revolution? A Reader (Greenwich, N.Y.: Fawcett Publications, 1968), 335; and Catherine C. LeGrand Frontier Expansion and Peasant Protest in Colombia, 1850–1936 (University of New Mexico Press, 1986), 163.

- Jesus Bejarano Avila, Camilo Enchandia, Roldolfo Escobedo, & Enrique Querez, Colombia: Inserguridad, Violencia y Desempeno Economico en las Areas Rurales (Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia, 1997), 133.

- Charles Bergquist, Ricardo Peñaranda, & Gonzalo Sánchez, Violence in Colombia 1990–2000 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Inc., 2003), 15; Nazih Richani, Systems of Violence (New York: SUNY, 2002), 68

- Garry M. Leech, Killing Peace, 78.

- Mark Chernick, “Elusive Peace: Struggling Against the Logic of Violence,” NACLA Report of the Americas 34, no. 2 (2000): 32–37.

- Scott Wilson, “Colombia’s Rebel Zone: World Apart,” October 18, 2003, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/world/issues/colombiareport/.

- Nazih Richani, “The Politics of Negotiating Peace in Colombia” NACLA Report on the Americas 38, no. 6 (May–June 2005): 18.

- Russell Crandall, Driven by Drugs: U.S. Policy Toward Colombia (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002), 88.

- See Stan Goff, Full Spectrum Disorder (New York: Soft Skull Press, 2004), 33.

- Wilson, “Colombia’s Rebel Zone.”

- As quoted from Juan Pablo Toro, “Colombia Say’s It’s Winning Vs. Rebels,” November 11, 2005, http://www.kansascity.com.

- Peter Gorman, “Marines Ordered into Colombia: February 2003 is Target Date,” October 25, 2004, http://www.narconews.com/article.php3?ArticleID=19.

- Jim Garamone, “U.S., Colombia Will Continue Pressure on Narcoterrorists,” April 12, 2005, http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Apr2005/20050412_563.html.

- As quoted in Constanza Vieira, “US Increases Colombia Involvement,” June 30, 2004, http://www.antiwar.com/ips/vieira.php?articleid=2915.

- Jason Webb, “Colombian Rebels Strike Again, Kill Eight Troops,” February 2, 2005, http://www.reuters.com.

- Associated Press, “Rebel Rockets Kill 14 Soldiers, Colombia Says,” February 1, 2005, http://msnbc.msn.com/id/6894272/.

- Jason Webb & Luis Jaime Acosta, “Marxist Rebels Ambush, Kill 20 Colombian Troops,” and “Marxist Rebels Kill 17 Colombian Soldiers,” February 9, 2005, http://www.reuters.com.

- William J. Pomeroy, Guerrilla Warfare and Marxism (New York: International Publishers, 1968), 313.

- FARC–EP, FARC–EP Historical Outline (Toronto: International Commission, 2000), 26 (italics added).

Comments are closed.