Also in this issue

Books by Anne Braden

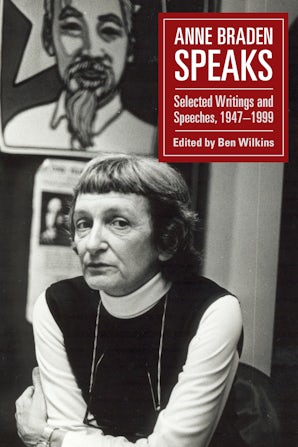

Anne Braden Speaks

by Anne Braden

Edited by Ben Wilkins