Background

In the 1980s the Brazilian economy suffered a long spell of stagnation and inflation caused by the foreign debt crisis affecting all indebted countries. That crisis triggered an acute inflationary process that reached 2,012.6 percent in 1989 and 2,851.3 percent in 1993, according to the general price index from the Getulio Vargas Foundation. The second half of the 1980s and the first of the 1990s saw the deployment of successive anti-inflationary plans, starting with the 1986 Plano Cruzado and ending with the 1994 Plano Real.1 The period also marked the end of the industrialization strategy known as “import substitution” and the onset of neoliberal policies in Brazil.

The last attempt to build an integrated industrial economy in Brazil relatively independent from the major powers dates back to the ambitious Second National Development Plan, the brainchild of General Ernesto Geisel’s government, and ended in 1979 when the foreign debt crisis started. After the plan, governments faced pressure from foreign creditors to collect large debt payments and a rapid inflationary process. The economy was then redirected toward exports to obtain hard currency. As a result, the balance of foreign trade turned positive in 1981 with a surplus that grew until 1994 when the balance became negative again. The average surplus in those years was $10 billion, money that was used to pay the interest on the foreign debt.

That effort created a vicious circle in which the government stimulated exports, purchased dollars from exporters by printing money or selling bonds, and sent the dollars abroad to serve the debt, thus generating strong inflationary pressures. When the economy was indexed, inflation grew stronger while fiscal deficits grew larger, a process that, after more than a decade, resulted in the hyperinflationary peaks of 1989 and 1993, as indicated above.

The acute economic crisis of the 1980s coincided with large-scale demonstrations against the military dictatorship and the demand for free elections. With a democratically elected civilian government in place, the economy grew again but could not escape the iron grip of foreign debt and inflation. It was in the context of the fight against the dictatorship that the São Paulo union movement and the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) were created, with Luíz Inácio Lula da Silva as leader. In the 1980s and 1990s, the PT gained in numbers and grew in structures and political influence, becoming the main opposition party under the governments of Jose Sarney, Fernando Collor de Mello, Itamar Franco, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

In the first direct election of the new democracy, Lula won the first round and everything pointed to his winning the second round too. Faced with such a scenario, the elites used the media to win the election for Fernando Collor de Mello. Collor was a politically weak candidate who resigned from office in 1992 before he could be impeached on charges of corruption. Lula was again a candidate in 1994 and 1998 but was beaten by Cardoso both times. In those years, a majority of PT leaders gradually changed the party’s electoral strategy, until they achieved a victory in 2002.

It is this change in strategy that explains why once in office, instead of deploying the alternative economic policy stated in the party’s program, Lula opted for a neoliberal program and subordinated economic growth and even social inclusion to creating solid economic fundamentals, a way, in his view, of pandering to the markets and paving the way to achieve other targets. This obsession with fundamentals, their real potential to help achieve the targets constantly mentioned by Lula in his speeches, and the contradictions this imposes are discussed below.

Economic Fundamentals & the Lula Government

Started in July 1994 the Plano Real won the war on inflation. But its very conditions—an overvalued and semi-rigid rate of exchange, high interest rates, and a large inflow of foreign capital, mostly speculative—defined its limitations. Internal contradictions in the plan accelerated the growth of foreign and domestic debt, turned the surplus in foreign trade into a deficit, and created large problems with the current accounts balance. External vulnerability and the international financial crises of the 1990s brought down the economy in late 1998.2

After this collapse, macroeconomic policy was changed, with three main priorities: low inflation, free-floating exchange rates, and generation of primary surpluses to avoid more debt. These new elements, introduced into the equation by Cardoso’s government, have been intensified by Lula’s.

In March 1999, the new inflationary plan was adopted with the Harmonized Consumer Price Index (HCPI) as the official inflation index. As the macroeconomy got in order, it went down in just a year to 19 percent, with inflation closing at 8.94 percent.

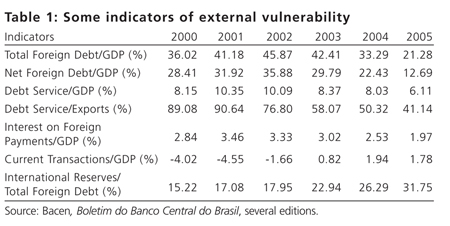

External vulnerability was significantly reduced due to the changes in exchange policy and the privileges granted to foreign capital, which were associated with the rapid growth of exports in the favorable international situation of the last few years.3 All indicators in table 1 are extremely positive, but credit for that progress cannot be given solely to the government.4

Since the end of the Cardoso administration, the foreign debt as a percentage of GDP fell from 45.87 percent to 21.28 percent in December 2005. In the same period, the foreign debt service fell from 10.09 percent of GDP to 6.11 percent, interest payments shrank from 3.33 percent to 1.97 percent.

Exports and the results in current transactions as a percentage of GDP have been the two most impressive items in the process of building more solid fundamentals for the economy. In the last three years of the Cardoso government current transactions as a percentage of GDP were negative but showed a tendency to improve and turned positive in the first three years of the Lula administration, thus confirming the evident reduction in the external vulnerability of Brazil.

On the fiscal front, the Lula government has continued and intensified the policy of creating large surpluses adopted in 1999. The president started by bringing the 3.75 percent target agreed to with the IMF to 4.25 percent of GDP. In the following years he has easily surpassed the highest surplus achieved by Cardoso (3.89 percent in 2002). In 2004 his surplus reached 4.6 percent of GDP and in 2005 it went up to 4.8 percent. But since interest payments have amounted to 7.26 percent and 8.13 percent of GDP in the last two years, debt has continued to grow because the surpluses, high as they have been, have not been enough to meet obligations. Thus Brazil has been nominally incurring a deficit of 3 percent of GDP.

When Fundamentals Do Not Help Growth

Brazil now shows much-improved financial and economic indicators, has greatly reduced its external vulnerability, and is seen by the markets as being well on the way to fiscal soundness. But it has not been able to use the situation to grow. While the world’s economy has grown by 4.3 percent, Brazil’s grew by just 2.3 percent. Latin America has grown as a region at the world average, but Brazil has only done better than civil war-torn Haiti, projected to grow 1.5 percent. Argentina has grown by 9.1 percent, Venezuela by 9 percent, and even Mexico, suffering from hurricanes, has grown by 3 percent, which confirms that Brazil has not been using its better economic fundamentals and the better international situation to restore its relative importance in the region and the world.

The fact is that, since being launched in 1994, the Plano Real has proved to be an enemy of economic growth. Only in the first two years of the Plan, 1994–1995, did Brazil manage to grow faster than the world average, as shown in table 2. Since then, the country’s performance has been below the world’s average, only approaching it in 2000 and 2004, when international conditions were exceptional. In every other year, growth has been mediocre or nil, as in 1998, 1999, and 2003.

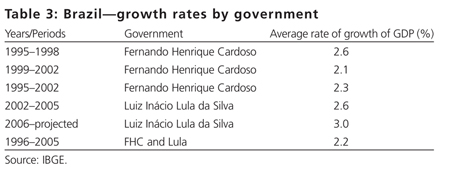

There has been very little difference from the point of view of growth between the successive governments in Brazil. In the first Cardoso term (1995–1998), average growth was 2.6 percent, while in his second term (1999–2002) it was just 2.1 percent (table 3). Over the three years of the Lula government, average growth has been 2.6 percent, a figure that will not alter much this year. The average for the last ten years (1996–2005), just 2.2 percent, is mediocre and not enough for the country to create enough jobs and give better living conditions to its citizens.

It could be argued that the Cardoso government had to face a series of international and domestic economic storms that checked growth, although his lack of success in this field cannot be blamed entirely on these events. In his first term in office, Cardoso had to face the Mexican financial crisis (1995), then the crisis in Southeast Asia (1997), and then the crisis in Russia (1998), with the result that the real collapsed and was sharply devalued in 1999. During his second period he had to face the cooling of the U.S. economy, the effect of the 9/11 attacks (2001), the crisis in Argentina, and, also in 2001, the energy crisis at home. Except for Lula’s first year in office (2003) when mistrust was still prevalent, Brazil has sailed on quiet financial waters. With the support of international markets and financial institutions it has managed to improve dramatically its financial, fiscal, and country risk indicators, as shown above. In fact, Lula has implied that under his administration Brazil will start a long cycle of growth. But growth has remained—so far—low and difficult and there are no hopes of seeing it pick up pace in the short term.

Table 4 clearly shows how much Brazil has fallen behind in comparison to developed economies, emerging economies, and even other economies in Latin America in growth in GDP per capita. In the past ten years (1996–2005), the growth of per capita GDP in Brazil has been only 0.7 percent, surpassing only Venezuela’s, which shrank by 0.5 percent. All other countries listed in the table have grown more, particularly China (7.7 percent), India (4.4 percent), and the emerging economies of Europe, such as Poland and Russia. Even when compared to the more modest growth rates of developed economies, Brazil’s performance has remained weak, in some cases achieving just a fourth or a third of their per capita growth. Not only has Brazil lagged farther behind developed nations in per capita terms, but it is in danger of being quickly overtaken by countries such as China and India, each with five times its population.

If the fundamentals of the economy are as solid as the government claims and the markets indicate, there is no justification for the lack of growth and for not profiting from the positive international situation. The bottom line is that building solid economic foundations is done precisely in order to grow. Unless the monetary stability achieved has become an end in itself or the fundamentals are not so solid after all, what is happening is that the country is once again missing a chance to correct many of its asymmetries and problems.

Delaying Growth: The Model of Stabilization

To understand the factors that have kept Brazil from growing and its rulers from flying higher, we need to look at the pieces that formed the backbone of the stabilization model, the Plano Real, since its inception in 1994. Only thus is it possible to see the trap the country has fallen into in order to guarantee monetary stability—paying the high price of low growth.

In the first stage (1994–98), the plan lacked a solid fiscal base and, to tame inflation, used a combination of an overvalued currency as an anchor for prices and very high interest rates to cool internal demand and attract foreign capital. At the same time, there was a sudden process of trade opening to keep a lid on inflation, disregarding losses suffered by domestic industry.

This mixture of measures did work and inflation fell to manageable levels (between 5 percent and 10 percent per year) but the results were disastrous for the country’s foreign accounts and public finances: from a fairly orderly balance of foreign accounts in 1994 the country went to a deficit of $33 billion in 1998 and the ratio of net public debt/GDP went from 30 percent to 43 percent (13 percentage points of GDP in just four years!).

Seeing such figures, certain economists have concluded that stability was achieved through taking on debt of such a massive scale that it will condition growth for years to come. The country’s external vulnerability made it highly sensitive to the foreign crises that shook the world’s finances starting in the late 1990s and forced Brazil to tighten its economy. The Russian crisis of 1998 sparked a fast flight of capital from Brazil and the only way out was to turn to the IMF and accept a new plan of stabilization which would prove to be even less amenable to growth.

In its ongoing second stage starting in 1999, the model was adjusted to rein in debt and keep prices stable. Exchange rates became flexible, prices were anchored by the Central Bank’s inflation targeting, and growing fiscal surpluses were included in the equation to create a more reliable ratio of debt to GDP and guarantee payments to creditors.

Monetary stability and debt control leave little room for growth, except in exceptionally positive international circumstances, as those predominating in the last few years. Even then, if opportunities are not taken, as is the case with the Lula government because of conservatism or fear of growth, the country will remain fated to live with low or mediocre growth rates.

The model being applied has been strongly anti-growth because its instruments smother production and work against public and private investment, raising the so-called “Brazil cost” associated with such factors as lack of investment in infrastructure and distortions in the tax system, and stopping changes needed to create sustainable development.

Three basic instruments have been utilized: interest rates, taxes, and public expenditure.

Maintaining very high interest rates (currently the highest in the world, hovering at around 11 percent per year) has inhibited consumers, cooled investments, and guaranteed a steady inflow of foreign capital looking to make a fast, easy profit. It has also prompted a revaluation of the real and made exports more difficult. Although the model has shown an outstanding performance and enjoyed a long spell of international growth, some industries such as footwear and clothing and even the automotive industry are already facing difficulties in sustaining their activities due to exchange rates. Brazil could face serious difficulties in one of its few dynamic industries if the signs of cooling in the world’s economy become true in the next few years. On top of all that, the high interest rates have snowballed public debt, which has made it more difficult to continue generating fiscal surpluses.

Since 1999, a favorite government tool for generating surpluses has been taxation. But high taxes raise the “Brazil cost,” lower profit margins for investors, and cool off the domestic market by taking away income from the population. Between 1998 and 2004, taxes rose from 29.7 percent of GDP to 35.9 percent. Worse still, almost 80 percent of all taxes levied are indirect and turn taxation into a strong instrument of wealth concentration.

The third instrument used to generate fiscal surpluses, cuts in public expenditure, has fed recession and kept the government from making investments in the infrastructure that could improve private-sector expectations and kick in new investments by convincing businessmen that there would be wider limits to their expansion. What has happened is that the government had to attend first to its mandatory expenses and serve the growing debt. Therefore budget cuts concentrated on investments and social security programs not protected by constitutional mandate or specific laws, such as health and education. With public investment reduced to a mere 0.5 percent of GDP, there was no way to create the state of trust that would help attract investments.

It is no wonder then that Brazil has a rate of investment that is below that of every major region in the world, according to research carried out by Brazil’s National Confederation of Industries (CNI), as shown in table 5. While the world has registered an average investment rate of 22.1 percent of GDP from 1995 to 2004, Brazil has registered one of just 19.3 percent. The difference has been even more striking when considered by regions: in that period, the Asian emerging economies invested an average of 32.6 percent of their GDPs per year, followed by the Eastern and Central European countries with 23.9 percent. Brazil is more at home in Latin America and Africa, but still showing low scores.

With such low levels of investment, there is no way to grow strongly over time. Worse still, without expanding production, any growth in demand triggers new pressures against prices, demanding that recovery be aborted to keep inflation down as happened in Brazil in 2000 and 2004. The three instruments are used again and the situation reverts to the stabilization trap: higher interest rates, cooler markets, less investment, more debt, higher budgetary surplus, and more budget cuts and taxes, which create a new period of low growth or stagnation.

Markets and the officials responsible for economic policy have claimed that the strategy will pay off in time, with sustained growth that will repay society for the sacrifices it has made. This remains a matter of faith, but one that benefits financial capital—indeed, benefits it a great deal! Critics of the model have claimed that, without major alterations, it will produce the deathly quiet of a cemetery, with a weaker economy, loss of industrial base, higher unemployment, greater poverty, and more social exclusion. After ten years of lukewarm growth, there is no sign of success and the burden of public sector debt still remains at levels of over 50 percent of GDP—without any major international crisis.

Conclusion

We have tried to show that the macroeconomic policy followed by the Lula administration has been successful and has improved the fundamentals of the Brazilian economy in the years since the end of the Cardoso government. However, the internal structure of the economic model has caused weak growth and fantastic profits for financiers and made it impossible to expect sustained growth—assuming that this is possible within the current capitalist world order.

In the first three years of the Lula government, R$263.3 billion have been paid to serve the foreign debt. In the same period just a tenth of that amount has been spent on the Programa Fome Zero, created to feed the poorest of the poor. The national bureau of statistics has shown that there was a slight decline in poverty in the country because of the program. But this cannot be seen as a change in the age-old catastrophic rates of social inequality in Brazil. We have tried to show here that the fundamental shift in macroeconomic policy seems to discard a policy of growth for good. And growth, stable growth over time, is the only way to create jobs and income, and to lessen poverty and social inequality in Brazil.

Notes

- ↩ Ipeadata, http://www.ipeadata.gov.br.

- ↩ The IMF and the international financial community put together a very large loan of U.S.$41.6 billion dollars to help Fernando Henrique Cardoso win the election against Lula. The fund provided U.S.$18.1 billion, six times what Brazil was qualified to receive. The World Bank and the IDB loaned U.S.$9 billion and the United States, Canada, and Japan provided U.S.$14.5 billion.

- ↩ On February 15, 2006, President Lula made into law his Decree 281 exempting foreign investments in government bonds from income tax and the financial movements tax. See J. Carlos de Assis, “Isenção de imposto para especulador estrangeiro, “http://www.desempregozero.org.br.

- ↩ Much of the improvement must be credited to the evolution of exchange rates. Between 1999 and 2002 the sharp devaluation of the Brazilian currency shrank the value of the country’s GDP in dollars, making the indicators much worse. Since 2003, the real has gained 40 percent in value before the dollar and the indicators have improved substantially. That explains why Brazil jumped from fourteenth to eleventh in the international ranking of economies, even without showing much real growth.

Comments are closed.