Books by Jonah Raskin

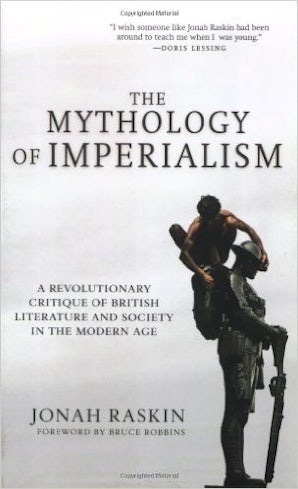

The Mythology of Imperialism

Preface by Bruce Robbins

by Jonah Raskin