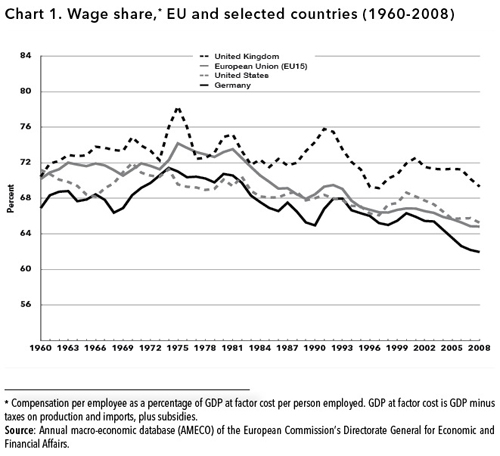

Correction: In “Chart 1” on page 20 of the print version of this article the lines in the legend denoting wage share for “United Kingdom” and “United States” should have been dashed.

There are three dimensions to the current, unprecedented global crisis of capitalism: economic, ecological, and political.

Let us look first at the economic dimension, which will be our main concern in this article. Capitalism is facing a major realization crisis—an inability to sell the output produced, i.e., to realize, in the form of profits, the surplus value extracted from workers’ labor. Neoliberalism can be viewed as an attempt initially to solve the stagflation crisis of the 1970s by abandoning the “Keynesian consensus” of the “golden age” of capitalism (relatively high social welfare spending, strong unions, and labor-management cooperation), via an attack on labor. It succeeded, in that profit rates eventually recovered in the major capitalist economies by the 1990s.

However, the system’s success, partially due to neoliberalism, in reviving profits engendered a potential realization crisis, due to low wages and investment. The dramatic deterioration in wages limited consumption, forcing workers to resort to increased borrowing. The decline in investment in physical capital went hand-in-hand with the growth of a casino economy, in which profits were funneled into speculation in financial assets. In the last two decades, the rapid financialization of the U.S. economy helped to increase demand through various wealth effects and debt-credit stimuli, despite the weakening of the underlying economy. Eventually, however, debt-led growth could not be sustained. Beginning in the summer of 2007, this solution also collapsed, and the capitalist economy has come to face a major systemic crisis, comparable to the Great Depression—except for the unprecedented state intervention moderating the visible dimensions of the downturn. Now, with the collapse of the financial mechanisms that allowed for all the debt, it is unclear how these state policies can overcome the realization crisis.

Second, consider the ecological dimension. Recovery efforts have been centered on maintaining growth and employment through high consumption. It is assumed that we can go on consuming as before, by means of magical technological innovations engendering ever higher energy efficiency. However, today the ecological limits to growth have been scientifically established, so we cannot return to business as usual. To sustain our environment, long-term economic growth must be zero or low—equal to the growth rate of “environmental productivity.” For this to be socially desirable, however, there has to be a guarantee of high employment and an equitable distribution of income. The latter is clearly at odds with capitalism.

Third, the depth of the present crisis has created holes in the legitimacy of neoliberalism. The rise in unemployment and inequality after the crisis in Western Europe, similar to the transition crisis of twenty years ago in Eastern Europe, will lead to serious political discontent. Thus, there is space for radicalization, but the left has yet to challenge the hegemony of capitalism.

In what follows we will focus primarily on the economic crisis of capitalism in Europe, West and East. Nevertheless, since this cannot be separated entirely from the simultaneous crises of the environment and of neoliberalism, we will return to these other dimensions of the general crisis of the system, when addressing possible political responses, in our conclusion.

The Crisis of the Neoliberal Era of Accumulation

Since the 1980s, the world economy has been guided by deregulation in labor, goods, and financial markets. This deregulation has been helped along by the transformation of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, which opened up new markets, provided a large reserve army of cheap labor, and relieved the pressure on the welfare states of the West to maintain decent living standards for the working masses.

The outcome has been a dramatic decline in labor’s bargaining power, as shown by the long-run decline in labor’s share in national income across the globe (see Chart 1). It should be noted that, although this global trend with regard to the wage share of income is striking, concealed within it is the fact that the very high compensation of CEOs and other top managers is included in total “wage income.” Since the “earnings” of these strata have increased dramatically relative to ordinary workers, the shift in the class basis of income is much sharper than the data indicate.

Declining worker power in this period has therefore led to widening profit margins, contributing to the recovery of profit rates. The neoliberal era also generated higher global profits for multinational firms, especially those in the financial sector.

Financial sector profits in many ways displaced profits from actual production. As finance became dominant, the investment behavior of business firms was increasingly shaped by a shareholder-value orientation. A shift in management behavior from “retain and reinvest” to “downsize and distribute” occurred. Remuneration schemes, based on short-term profitability, shifted the orientation of management toward shareholders’ objectives. Unregulated financial markets and the pressure of financial market investors created a bias in favor of asset purchases, as opposed to asset creation. At the same time, most of the efforts of macroeconomic policymakers were skewed toward retaining the confidence of volatile financial markets.

Markets have been deregulated mainly to support the interests of rentier-capitalists. Consequently, the relationship between profits and investment changed: higher profits did not automatically lead to higher investment. In spite of higher profit rates and a boom-euphoric business environment in many countries, economic growth rates have been well below their historical trends. In a deregulated financial environment, it would be irrational for capitalists to give up the short-term, high-profit options in financial speculation and engage in long-term, irreversible, and uncertain physical investment.

The decline in the labor share and stagnant real wages has been a potential source of a realization crisis for the system. Profits can only be realized if there is sufficient effective demand for the goods and services produced. But the decline in the purchasing power of labor has a negative effect on consumption, given that spending out of profit income is relatively lower than that out of wages (a dollar transferred from a worker to a capitalist reduces total consumption spending). This further reduces investment, because capital spending depends on the demand for the products that capital helps to produce.

Financial innovations seemed to offer a short-term solution to any realization crisis: debt-led consumption growth. Of course, without the unequal income distribution, the debt-led growth model would not have been necessary. In the United States and in parts of Europe, household debt increased dramatically. The increase in mortgage debt and house prices reinforced one another. Increased housing wealth served as collateral for further debt, and then money from the loans fueled consumption and growth, maintaining high profit rates. This phase, despite growth rates lower than in the 1960s, provided the basis of a long “expansion,” with the attendant peculiarities of profits without investment, growth without jobs, and increased financial fragility. Debt-financed consumption may fuel growth, but debt eventually has to be serviced. Because of high debt levels, the fragility of the economy to possible shocks in the credit market also increases.

The deregulation of financial markets and the consequent innovations in mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations (CDO), and credit default swaps facilitated the debt-led growth model. These innovations, combined with the “originate and distribute” model of banking, have multiplied the amount of credit that banks could extend, given the limits of their capital. The premiums earned by the bankers, the commissions of the banks, the high CEO incomes (thanks to high bank profits), and the commissions of the rating agencies all created perverse incentives that led to a short-term mindset and ignorance about the risks of this banking model. Even if the risk of default in the subprime credit market was known, it was not perceived as a major issue. Most of these loans were sold to other investors in the form of mortgage-backed securities with high ratings, and in case of default, the houses could be repossessed. As long as house prices kept increasing, this remained a profitable business for the creditor.

But this banking model was very risky, a time bomb destined to explode. Distress in the subprime markets eventually triggered the explosion. First, the market for CDOs, then the interbank market, and finally the whole credit market collapsed on a global scale.

It is interesting to ask why it took so long for the bomb to explode. The reason is the endogenous evolution of expectations (Keynes’s “animal spirits”). As the debt-led growth model produced high short-term growth and profits, optimism was stimulated and fed on itself, so that risks were more and more underestimated, even by those who were conservative at the beginning. In a competitive world, even those who see the risks are forced to take risky positions, if they are to keep their jobs as dealers, bankers, or CEOs. Just a couple of weeks before the big collapse in July 2007, the ex-CEO of Citibank, Chuck Prince, said, “[W]hen the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.”1 When the shock came, a credit crunch and the collapse of the debt-led growth model was inevitable.

A crisis might conceivably have been averted, at least for a while, if something had been done about the growing inequality in income and wealth that would eventually stifle aggregate demand. But the powerful global elites who have great influence over global policy-making would not agree to this solution. Everyone hoped for a “soft-lending” that would correct the bubbles without touching the distribution issue.

The debt-led consumption model helped generate a current account deficit in the United States that exceeded 6 percent of the Gross Domestic Product. This deficit was financed by the surpluses of developed countries such as Germany and Japan, “emerging economies” such as China and South Korea, and the oil rich Middle Eastern nations. In Germany and Japan, current account surpluses and the consequent capital outflows to the United States were made possible by wage moderation, which suppressed domestic consumption and fueled exports. This again was an outcome of the crisis of distribution.

In emerging economies such as China and South Korea, the experience of the Asian and Latin American crises stimulated a policy of accumulation of foreign reserves as a hedge against speculative capital outflows. Here, the international dimension of inequality played an important role: these countries, threatened by the free mobility and volatility of short-term international financial flows, invested their current account surpluses in U.S. government bonds instead of financing their domestic development plans.

In the European context, strong wage moderation in Germany created further imbalances within the West, as well as between the East and the West. Within the West, the lack of a comprehensive industrial policy and public investments created a rise in the costs of production (unit labor costs, that is, wages divided by productivity) in countries such as Spain, Greece, Portugal, Italy, and Ireland. Thus, the high current account surpluses of Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and Finland existed along with widening trade deficits in the other EU countries. The low level of wages in Eastern Europe also did not save its countries from running high current account deficits, due to high imports from the international supplier networks of the European multinational companies, as well as the high profits of these foreign investors (repatriated as well as reinvested).

Western Europe’s Economic Malaise

Although the crisis originated in the United States, the impact has been heavier in Europe, partially due to the larger size and faster implementation of fiscal stimulus in the United States. According to the OECD Economic Outlook (March 2010), U.S. GDP fell by 2.6 percent in 2009, whereas the Euro area contracted by 4 percent, and the United Kingdom by 4.9 percent. The United Kingdom is experiencing a deeper recession, largely because of the housing bubble and household debt. The prospects within the Euro area are also rather diverse. Both German and Italian GDP declined by 5 percent in 2009, while French GDP contracted by just 2.6 percent.

There are also diverging sources of fragility in different Western EU countries. As export markets shrink, Germany is suffering from the curse of its neo-mercantilist strategy—growth based on export markets via stagnant or declining wages, which had led to decades of stagnant domestic demand. The chronic current account deficits of Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy—the outcome of the historical failure of the European Union and its single currency to provide for regional convergence—are now proving to be detrimental, as financial investors are asking for much higher interest rates in return for the government bonds of these deficit countries. This is even bringing the stability of the Euro into question.

The ability of these countries to respond to the shocks is also constrained by their fiscal capacity. Austria is paying high interest rate spreads, due to the excessive expansion of its banks in Eastern Europe. Both Ireland, with its disproportionately large banking sector and the bust of its housing bubble, and Spain, with the collapse of the housing bubble and the consequent contraction in construction, are expected to be in continuing recession, with limited capacity to reverse course.

Real wages began to turn down decisively in 2010 in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, and Italy, following wage cuts arising with the onset of the crisis in practically all European countries. Greece, Portugal, and Spain, in particular, are under the ax of the EU and financial markets, and are being compelled to increase their competitiveness via deep real wage cuts, as part of a more general shock therapy in these countries. Sharp and long-lasting increases in unemployment, augmenting the industrial reserve army, are likely to make the wage losses much stronger, leading to dramatic further declines in labor’s bargaining power.

The case of Japan shows that during the initial phase of a deflationary crisis (or a long-lasting recession), labor’s income share either stagnates or slightly increases, but as recession and deflation persist, even nominal wage declines take place. In Japan, for example, the wage share declined by 8.9 percent between 1992 and in 2007.

The decline in the wages in Eastern Europe will also add further international competitive pressures on wages in Western Europe, whose impacts will be different on different groups of workers. Temporary workers are losing their jobs first, while more qualified workers are being retained. However, some skilled workers in the automotive industry, metal industry, and finance have already been affected. Furthermore, future cuts in government social expenditures will also asymmetrically affect labor, with an additional burden on women’s unpaid care work.

Unemployment increased substantially in the United Kingdom and in the Euro area in 2009, and further unemployment is expected in 2010. Particularly high increases in unemployment emerged in Ireland and Spain. Overall, their greater fiscal capacity has helped many Western European countries to weather the shock better than developing countries. However, without the support of strong fiscal stimuli, a long recession seems very likely. Although the economies may have hit bottom, they may not be able to climb out for a long time, and further deteriorations cannot be excluded.

The Eastern European Slowdown

It now appears that the early optimism about the decoupling of the East from the West has proved to be wrong. The fundamental problem of the region was an excessive dependence on foreign capital flows; when these were reversed by the crisis, catastrophe followed. Consequently, the emerging markets of Eastern Europe have been severely affected by the credit crash, capital outflows, and the currency crises accompanying the banking crisis. Following the initial shock of transition from planned to market economies and a decade of restructuring, these countries are once again facing the costs of integration into unregulated global markets.

The difference between this crisis and ordinary boom-bust cycles in the periphery is that this is a global, not simply a regional, crisis. It originated in the core capitalist nations, but the consequences for the periphery of Europe have been and will be heavier. The credit crunch also has a global dimension, which makes the usual capital inflows after a typical bust phase and resulting currency depreciation unlikely. Export markets have severely contracted, and the depreciation of the local currency, which is a usual outcome of boom-bust cycles, will now only have a negative balance sheet effect, with no positive demand effect. The extent of debt-led consumption growth and household debt, payable mostly in foreign currency, has made this crisis more severe, and if local currencies depreciate further, debt burdens will rise further as well, deepening the crisis.

The slowdown in global demand, the decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, portfolio investment outflows, the contraction in remittances, and the credit crash are affecting all the developing countries, but the degree of accumulated imbalances will determine the differences in the depth of the effects among these countries. The Baltic Countries, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, are more exposed than Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, and Slovakia. But even the latter group is suffering from the slowdown in global demand and the decline in FDI inflows.

The contraction in remittances can also become an issue in the future. Excessive dependence on export markets and a dangerous specialization in the automobile industry—in the case of Slovakia in particular, but also in the Czech Republic and Slovenia—have turned out to be major risks. Poland is only experiencing stagnation rather than recession, thanks to its more diversified market and large domestic economy, with a lower trade volume as a ratio to GDP. Both Slovakia and Slovenia have escaped turbulence in the currency markets by adopting the Euro; however, their problem will be a permanent loss of international competitiveness relative to their competitors, which are devaluing.

The notion that Eastern European countries would not experience bottlenecks regarding current account deficits, thanks to FDI serving as a major source of finance for the deficit, proved to be a myth. It is true that FDI is still more robust than other capital flows, but in the first quarter of 2009, FDI inflows fell by 20-80 percent, reaching 2001-2002 levels.2 Although the current account deficits are also falling because of lower imports due to the slowdown, FDI is now financing a declining part of the deficits. Furthermore, FDI not only finances but also creates current account deficits; the average profit repatriation rate has been 70 percent in the region, and FDI has been about equal or less than the repatriated profits in Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic.

A major difference between what transpired in Eastern Europe and what happened in East Asia and Latin America in past crises is that Eastern European countries relied on parent banks in the developed nations that had a longer-term strategy in the region. However, given the crunch in wholesale credit markets, the ability of parent banks to maintain credit to the region is now exhausted. Borrowing requirements in the Western countries are also creating rival investment opportunities for limited global funds. Currency depreciation in Eastern Europe, along with recession, will lead to increases in nonperforming loans and further affect the parent banks’ approach to Eastern affiliates.

The Baltic States and Bulgaria have currencies pegged to the Euro, and if they cannot maintain these pegs (which require these countries to have access to Euros with which to buy their own currencies to maintain the pegs in case of capital outflows), more devaluations will occur, and these will trigger further contagion effects in the region. For example, Swedish banks in the Baltic States and Austrian banks in Bulgaria, along with their governments, are pushing to maintain the pegs and avoid devaluation, in fear of high default rates on loans. Local governments also stand behind the pegs. However, preserving overvalued fixed exchange rates under the current policy framework will come at the cost of a very deep recession and deflation, which will create a de facto real devaluation. The mechanism for this seems to be massive wage cuts, as in Latvia.

The consequences of an unmanaged devaluation following a market-made currency crisis might lead to very severe distributional effects, as was the case during the Asian and Latin American crises. If a nation’s currency buys less foreign currency, imports become more expensive. If the economy depends on imports, as many do, devaluation in turn leads to inflation. Workers will suffer from this inflation more than the wealthy. So far, the depreciation rate has been moderate, and inflation has been restrained by a deflationary environment and falling commodity prices. However, both can become more severe in the future.

Unemployment in all the East European economies in the EU (New Member States) has grown significantly, with the sharpest increases taking place in the Baltic countries. Real wages have fallen in Hungary, the Baltic countries, Romania, the Czech Republic. The austerity programs in Hungary, Romania, and Latvia will further reinforce the pressures of the crisis.

In the Eastern European economies, the record of GDP, employment, and real-wage growth over the past twenty years has been shocking: first a transition recession and then a global crisis. The gains in terms of growth and wages are far from spectacular. Employment has at best stagnated, and it has decreased in Romania, Estonia, Lithuania, and Hungary. Real wages have stagnated in Hungary and Slovenia, even fallen in Lithuania and Bulgaria. Real wage growth overall has lagged behind productivity growth. Even in Romania, where real-wage growth was maintained for a time, it never exceeded improvements in productivity. This does not look like a politically and socially viable balance sheet.

Reactionary Policy Responses

All advanced countries reacted to the crisis with unprecedented rescue efforts. Monetary policy tools were mobilized; financial rescue packages were created in the form of guarantees of private deposits, state participation via capital injections into banks, and even nationalization and purchases of “toxic assets”; and fiscal rescue packages were initiated, albeit slowly, in the form of new spending on public goods and services, help for consumers (tax cuts and transfers), and stimulus for firms (corporate tax cuts and sectoral subsidies). The U.S. fiscal stimulus was the largest—if still meager in terms of what was required—while European efforts were much smaller in size (as a percentage of GDP).

Generally, fiscal measures have been relatively inadequate. In thirty-two countries, stimulus spending in 2009 was equal to just 1.7 percent of GDP, less than the 2 percent recommended by the IMF. Rescue packages were based on relatively optimistic forecasts, and financial measures have outweighed fiscal measures by a factor of ten.3 In Ireland, fiscal policy was actually contractionary. In addition, some of the financial measures may be very risky: purchase of high-risk U.S. bank financial instruments (Germany); overexposure to the possibility of Eastern European defaults (Austria and Sweden); and lack of any penalties for banks that do not make loans after getting public monies.

The composition of the fiscal packages was also inadequate: in the most advanced economies, only 3 percent of total spending is on employment, just 10.8 percent on social transfers to low-income households, and 15 percent on infrastructure.

Apart from the size of the packages, one major problem in the European Union is the absence of a coordinated policy, one that addresses the differences among the nations in the Union. In 2009 the European Commission asked that countries implement a stimulus plan equal to 2 percent of GDP, but divergences within the EU were not sufficiently addressed. The increase in risk evaluation of the government bonds of Greece, Spain, and Portugal by financial speculators in 2010 shows that these divergences are the major Achilles’ heel in the EU. To make matters worse, market players and neoliberal economists have been pushing for fiscal discipline to prevent sovereign debt default and future inflation.

Overall, what is missing is any grasp of the underlying causes of the crisis. There is an overemphasis on low interest rates in the United States and very little debate about the liberalization of financial markets. This has meant that reforms have been inadequate, with few real demands made on the financial institutions responsible for so much of the crisis. Although the costs of the rescue packages are clear, no effort is being made to make the responsible and the wealthy pay. The tax on bank bonuses and balance sheets in the United Kingdom only targets a small dimension of the problem of inequality. Policies to address a major root of the crisis, the dramatic pro-capital shift in income distribution, are nowhere to be found. With regard to global imbalances, much of the emphasis is on the overconsumption of the United States or low wages and an undervalued currency of China, rather than wage dumping and stagnant domestic consumption in Germany.

Even before the call for budget cuts, it would have been difficult to label the policies as Keynesian. True Keynesian policies would foster a broad program to stimulate investments through public initiatives as well as incentives to the private sector, a re-regulation of the financial system, and, at the international level, capital controls and fixed exchange rates. With the current balance of class power, ruling elites will not voluntarily implement Keynesian policies. Even to return to the “golden age” of managed capitalism would require major organizational efforts by working people, efforts that would effect a radical shift in class power. In the absence of such a shift the modest expansionary anti-crisis policies proved to have a short life, and massive budget cuts are on the way with devastating effects on the working class.

In Eastern Europe, the concerns of the European Union are shaped by the interests of the multinational corporations, in particular Western banks, and are limited to maintaining currency stability rather than employment and income. The European Union actually delegated the problems of the Eastern European economies to the IMF, albeit with some financial support to prevent a big meltdown of Western European businesses.

With the IMF, it has been pretty much business as usual, despite the seemingly diverse discourse. Faced with the pressure of capital outflows, Hungary, Latvia, and Romania have resorted to the IMF. As was the case for developing nations in the 1990s and early 2000s, IMF policies are again much more restrictive than what the IMF finds appropriate for Western European countries such as Germany. The unconditional credit line to Poland is the only new tool the IMF has used. Otherwise Hungary, Romania, and Latvia have been pressured to accept strongly pro-cyclical fiscal policies. Fiscal discipline is still the norm, and cuts in public sector wages and pensions are part of the recipes. In Latvia, public wage bills have been cut by 23.7 percent, pensions by 10 percent. Together with increases in the Value Added Tax (VAT) rate from 18 to 21 percent, these were the conditions to which the Latvian government had to agree in order to get the second tranche of the IMF package. In Estonia and Lithuania, a 20 percent cut in public wages and a reduction in social benefits was enforced. Capital controls to avoid speculative outflows or a managed devaluation are not even mentioned in the IMF or EU debates.

There Is an Alternative!

There is great public discontent with the way ruling governments have reacted to the crisis. Ironically, this has decreased the legitimacy of any policy alternative that includes “collective” mechanisms in governance or nationalization. There is, however, a window of opportunity, for the first time since the fall of the Berlin Wall, to argue that capitalism is economically, ecologically, and politically unstable and unsustainable. The road to channeling popular discontent toward an alternative sustainable, egalitarian, democratic, participatory, and planned socialist economic model is rocky, but we now have advantages. It is clear that higher profits do not lead to investments or more jobs; growth does not mean a decrease in inequality; and capitalist market economies are prone to systemic crisis. However, to formulate policy alternatives, it is important to emphasize what has caused the crisis. This is not just a crisis of improperly regulated markets. It is a crisis of unequal distribution, and it should be asked why labor continues to suffer. Business as usual is not an option.

Our starting point must be the urgent problems of employment, distribution, and ecological sustainability:

First, fiscal policy has to be centered around a public employment program and a distributional policy. Public expenditures in labor-intensive services like education, child care, nursing homes, health, community and social services, as well as in public infrastructure and green investments, should be made. These are also areas in which the economy can be redirected toward sustainable and solidaristic development. Such services are now provided either at very low wages, often as luxury services for the upper classes, or via unpaid female labor within the home. They should be provided by the state or by nonprofit organizations, which must be legally bound to redress gender disparities.

For ecological sustainability, there must be a shift in the composition of demand toward long-term green investments; this cannot be achieved without active public investments.

Regarding private-sector employment, it is important to avoid “socialization of the costs.” That is, working people and the unemployed should not have to pay the costs of the irresponsible behavior of global capital. An example would be where some firms use the crisis to implement their long-term downsizing strategies. “Short work” regulations are being used in many European countries to tame unemployment—government transfers offset part of the wages lost due to employer-mandated shorter work hours. An alternative would be to make the employers pay the costs through legal measures that freeze firings and implement wage floors. In firms that are in a position to distribute dividends and pay high managerial wages, the logical thing would be to ban layoffs. If the firing freeze leads to bankruptcy in certain firms, these firms can be revitalized under workers’ control, supported by public credits. Widespread examples of that were seen in Argentina during the last decade, as a survival strategy of workers in shut-down companies, which often closed without paying past wages and severance pay. As of 2007, ten thousand people were employed in self-managed businesses in Argentina. In cases of sectors such as the auto industry, under threat of mass layoffs, socialization and restructuring should be considered. In the auto industry, there could be a shift of focus toward the production of public transport vehicles and a gradual transfer of labor toward new innovative sectors.

The stimulus, employment packages, and green recovery plans should be financed from progressive income and wealth taxes, higher corporate tax rates, inheritance taxes, and taxes on financial transactions. This would make those responsible pay for the costs of crisis, and would avoid future budget cuts in social expenditures, education, health, child, and elderly care.

Tax rebates and subsidies to low-income groups or extended unemployment benefits have been typical short-run solutions. However, these do not correct the overall deterioration in working class lives. This is not only an egalitarian but also a macroeconomic concern. Wage-moderation policies only worsen the demand deficiency problem and ensure a future of low wages. In order to address the most fundamental aspect of the crisis, economic policy must first solve the distributional crisis. There must be a substantial shortening of work-time (in parallel with the growth of labor productivity), with upward wage corrections. The high profits of the past are responsible for the crisis, so now the recipients of these profits have to pay the costs.

This is not only a crucial answer to the problem of unemployment; it is also an answer to the ecological crisis: sustainable development requires zero or low economic growth in the developed countries, so full employment can only be achieved through shorter working times. The income losses for the working masses can be prevented through substantial redistribution. Shorter working hours will also help us to achieve democracy in decision making, by giving workers time for participation.

Second, the redesign of the financial sector is urgent. Regulation is important but insufficient; the financial institutions have an amazing capacity to avoid regulations through new innovations. The crisis has shown us that large private banks are exploiting their advantage of being “too big to fail.” Yet the challenge for us is to ensure the finance of socially desirable large new investments—in the energy sector, for example. What needs to be built is a public finance sector, not merely state-owned, but rather collectively owned, with the full participation of workers and other stakeholders in all decision making. This publicly owned finance must have completely transparent accounts. Only then can the following financial regulations be pursued to deliver socially desirable outcomes: full regulatory over-sight for all financial institutions, full accountability of the decision-makers, counter-cyclical capital requirements, and the elimination of off-balance sheet instruments.

Third, the need for public ownership of financial institutions opens up new questions about critical economic sectors that society cannot leave in the private sector. The economic crisis has indicated that finance and housing are clear candidates for public ownership. The energy crisis is telling us that the energy sector and alternative energy investments also require public ownership. Problems with private pension funds, as well as private suppliers of education, health, and infrastructure, are showing us that social services are too critical to be ruled by private profit motives. A creative and participatory public discussion should investigate other sectors where public ownership would produce more egalitarian and socially efficient outcomes. These suggestions are not meant to praise the public sector as such, but are rather a call for participation and control by the stakeholders (workers, consumers, regional representatives) in the decision making mechanisms within a public and transparent economic model. Such a shift in decision making also facilitates economy-wide coordination of important decisions for a sustainable and planned development based on solidarity.

Fourth, regarding the international aspects of the European Union, how or whether the West supports the South and East in weathering the current global crisis will be critical for the political credibility of the Union. The most important obstacle today to initiating a progressive economic policy in Europe is the speculation on public debt and the governments’ commitment to satisfy the financiers. Public finance has to be unchained via debt default in both the periphery and the core. Alternative policies must involve public investment programs with a focus on regional development. EU-level public investments, financed by EU-level progressive taxes, must play an active role in economic reconstruction. Another important fact that has become clearer in the wake of the global crisis is that capital account openness creates turbulence and structural problems, particularly in emerging economies. While keeping the Euro in the current Eurozone countries under the conditions outlined above is perhaps practical, in Eastern Europe the insistence on preserving the overvalued pegged exchange rates means ignoring the need for a major adjustment in the exchange rate. In this case, the devastating risk of depreciation/devaluation can only be overcome with capital controls and a managed devaluation of the currencies, along with price controls.

If these are not to be mere stopgap measures, however, they have to be part of a longer transition to a new society. It is impossible to “save capitalism from itself.” The goal toward which these practical measures should be directed is not simply one of easing the conditions of most people in the present crisis (a Sisyphean labor under capitalism) but also initiating a “long revolution” aimed at the creation of a collective society.

Notes

- ↩ “Citigroup chief stays bullish on buy-outs,” Financial Times (July 9, 2007).

- ↩ Gabor Hunya, FDI in the CEECs under the Impact of the Global Crisis: Sharp Declines (German), Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Database on Foreign Direct Investment in Central, East and Southeast Europe (May 2009).

- ↩ Sameer Khatiwada, “Stimulus Packages to Counter Global Economic Crisis,” Discussion Paper, International Institute for Labor Studies (2009).

Comments are closed.