A Note from Bob McChesney. This could be retitled “Notes from a Former Editor” as I served with John Bellamy Foster, Harry Magdoff, and Paul Sweezy as one of MR’s coeditors from 2000–2004. I stepped down from the post to devote more time to activism around media and communication issues. Regular readers know that I have continued as a contributor over the past nine years, and this issue’s Introduction marks my eighteenth article in the magazine since 2008. Most of those, like the one herein, were written with Foster.

Most of my research and activism has centered on the political economy of communication. With the increasing importance of media to everyday life and the exercise of power, as well as the digital revolution, there is growing and considerable interest in the area. That the work specifically translates into crucial political fights elevates its importance.

Nowhere is that more true today than in Latin America where the survival of popular politics depends to no small extent on how the raging media battles are resolved. “I believe that better than constructing roads, hospitals, and schools is to construct the truth. Lies have destroyed Latin America,” Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa said in a May 2013 interview. “I think one of the main problems around the world is that there are private networks in the communication business, for-profit business providing public information, which is very important for society. It is a fundamental contradiction.” (“Ecuador’s President Attacks US Over Press Freedom Critique,” TheRealNews.com, May 21, 2013).

During my time as coeditor, communication colleagues would sometimes wonder what I was doing at MR. After all, I was a media scholar, and MR was many things, but it was not a magazine known for its work on communication. I explained the singular importance of the MR tradition, of the work of Sweezy, Magdoff, Leo Huberman, and Paul Baran, in my intellectual and political development. I also explained the importance of the MR work on advertising, monopoly, and technology in developing a radical critique of media and communication. But I had to concede the point, nonetheless.

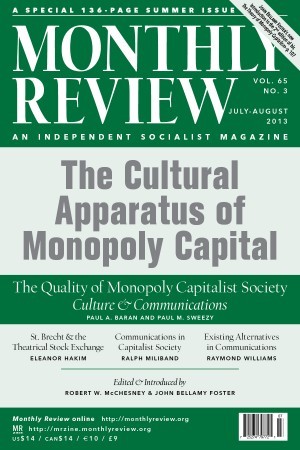

Imagine my surprise, then, when Foster informed me two years ago that two drafts of a missing chapter of Baran and Sweezy’s magisterial Monopoly Capital (1966) had been discovered in their papers. Not only that, it was a chapter on media and culture. I was shocked, to say the least. Foster provided me with the backstory: it was meant to be the penultimate chapter of the book, but when Baran died in 1964, Sweezy elected to leave it out (after doing additional work on it) as the book was already quite long and there remained unresolved issues with it.

As soon as I read the manuscript, I knew it had to be published. But what was media and culture doing playing such a prominent role in their signature work of political economy? As fate would have it, I had just come across a largely unknown and extraordinary pamphlet from 1962 by the British Raymond Williams on the need for a radical politics of communication to become a main part of socialist politics. I knew that Williams considered himself close to Monthly Review and was writing for it at the time. I could find common themes in the two works. It seemed like there was smoke, but was there fire?

Foster and I then spent many months on an intellectual odyssey which revealed that a rather sizable cohort of radical intellectuals were pursuing similar themes in the late 1950s and early ‘60s on the importance of media and communication. They investigated the centrality of the “cultural apparatus” (as they sometimes referred to it) to understanding the nature of modern capitalist societies, to developing effective strategies for socialist politics, and, most intriguing, to offering a vision for the constituent elements of a non-capitalist and post-capitalist democratic-socialist media system. It was the sort of unflagging criticism of capitalist media and the actually existing communist media systems that would be embraced by the New Left.

Besides Baran, Sweezy, and Williams, some of these figures included C. Wright Mills, Herbert Marcuse, Ralph Miliband, and E.P. Thompson. We even discovered a powerful critique of the Federal Communications Commission by Huberman and Sweezy that had appeared in MR in 1958 and was entirely unknown in the communication literature. We realized there was a significant body of work here that was largely unknown to scholars of the left or of media, so we decided to publish some of it along with the missing Baran-Sweezy chapter in this summer issue.

As readers will see, we believe this body of work is of significant value to current political struggles, and to a real breakthrough in how we think about post-capitalist social formations. For Ecuador’s Correa the solution is clear: “There should be more public and community media, organizations that don’t have that conflict between profits and social communication.” It is not just that capitalism is incompatible with a decentralized, uncensored, well-funded, open, nonprofit, and noncommercial media system—i.e., a communication system meant to empower people. More to the point any socialism worthy of the name must veer strongly in that direction or give up the fight for a better world.

While MR’s June special issue, “Public School Teachers Fighting Back,” focusing on the national implications of the 2012 Chicago Teachers’ Union strike, was still at the printer, the struggles of teachers once again hit the front page of newspapers throughout the United States. In late May 2013 the Chicago Public Schools announced that it would be shutting down fifty-four public schools, most of them serving the poorer, primarily minority districts of the city. A Chicago Tribune poll indicated that less than 20 percent of the population in the city agreed with the closure strategy (Educational International, “US: 50 Schools to Be Shut Down,” May 30, 2013, http//ei-ie.org). The Chicago Teachers’ Union unleashed three days of protests. Twenty-six protestors, including teachers, were arrested; over a hundred people were issued citations; students boycotted tests, while parents and community members came to the support of the teachers.

In Seattle nineteen high school teachers at Garfield High launched in January what is said to be the first boycott by teachers of standardized testing in U.S. history, directed against the computerized Measures of Academic Progress (MAPS) test. The movement spread to other schools in Seattle (and is being replicated across the country), drawing massive support from students, parents, and community members. On May 13, 2013, the Seattle Schools Superintendent announced that high schools could opt out of the test, constituting a resounding victory for the Seattle community. Five hundred school boards in Texas—and others in Florida—have now passed resolutions favoring reduced use of standardized tests. Clearly, the battle against the privatization and corporate takeover of K–12 education in the United States is now in full swing.

Those interested in organizing around this question can purchase bulk orders of MR’s “teachers fight back” issue at MR Press or over the phone at 212-691-2555. In addition, we would like to announce the publication by Monthly Review Press of Henry A. Giroux’s important new book, America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth, which is available for $16.95 (plus postage) at https://monthlyreview.org/press.

Correction: In Samir Amin’s “The Surplus in Monopoly Capitalism and the Imperialist Rent” (MR, July–August 2012) there was an error on page 79 in endnote 1. The clarification states that the rate of exploitation is equal to “wages divided by profits”; in fact, it should be the opposite.

Comments are closed.