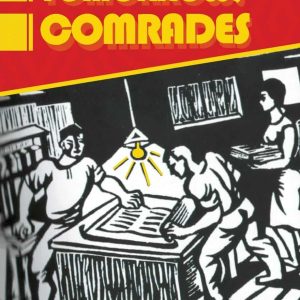

If ever there were a more urgent moment to read a novel due to the political climate devolving into fascism, that moment is now, and that novel is Until Tomorrow, Comrades (International Publishers), by Manuel Tiago, the pen name of Portuguese writer and Communist leader Álvaro Cunhal. The newly released English translation by Eric A. Gordon is brilliant, lively, and natural. All of Tiago’s novels reflect the struggles of members and leaders of the Portuguese Communist Party in their resistance to António de Oliveira Salazar’s fascist government, which ruled from 1932 until its downfall in 1974. The struggles rise from the page because Tiago incarnates events and action in well-drawn, three-dimensional characters inspired by his own experiences.

Until Tomorrow, Comrades is the longest in a complete series of eight other translations Gordon has done of Tiago’s novels. In his foreword, Gordon reveals that he decided to translate this novel last for two reasons: “As a sort of grand finale to the project, and because, knowing how seminal a work this had become not just in Portuguese literature but in the entire cultural understanding of the fascist period, I wanted to become as practiced and fluent with Tiago’s language and thought as I possibly could” (xii).

Having read all of Gordon’s translations of Tiago’s works, I can say he has achieved the ironic goal of all literary translators: to become invisible. When a translated work reads as if it originally had been written in the translated language, it is a masterful recreation for a new audience who cannot read the work in the original language. Gordon has reproduced the three-dimensionality of the characters in a way that could be described as warm and intimate, and even folksy. As I read, every detail of each character, from their clothes to their gestures or way of speaking, was so clear, drawing me into the action and making me care about what was happening. Well-delineated characters are perhaps more important than plot, because they are what keep readers’ attention and bend their sympathies. Gordon summed up this feature of the novel as granular, and I quite agree.

The action of this novel can best be described as sprawling, as Gordon observes in his foreword. It cannot be stressed enough, however, that action only can be performed by the characters: the plot begins and ends with them. The unique qualities each character brings to the saga intertwine like threads in a skein of yarn. Following all of the threads to their conclusions is rewarding, illustrative, and instructional. The truth is, it is a novel you could open to any page and find something to talk about.

The main characters in this novel are grouped into clusters of operatives in the resistance. The emotionally charged relationship between the characters of Vaz and Rosa is intensified for the reader by their deep involvement in clandestine work. The separation of Maria from her invalid father (an elderly anarchist) is poignant because it is a sacrifice they mutually agree to in order for her to fully engage in the resistance. Maria seems to always have some sort of emotional drama. Afonso comes into her life; he appears to have just fallen into the movement because he had no clear path in life. An unstable sort, he represents the types of people who are marginally useful to the cause. In contrast, Ramos is an energetic, humorous, and vital man, in the prime of life and full of wit. The party directs Maria to be the companion of António, a former student. Paulo is a militant who remains somewhat mysterious, as we must make many inferences in order to know him. Gaspar tries hard, means well, and attempts anything, often without success. Finally, Marques is an experienced party leader with a fatal flaw that leads him into many mistakes.

It might be tempting for some readers to dismiss this work because it takes place in the 1940s, when societal roles for men and women were distinct and often very different from today. Stereotypes were rampant as well. However, the extraordinary times in which these individuals lived created some extraordinary characters. There are two lessons here: First, never judge historical fiction or works written in another time or culture through the lens of our values. Readers must go to the work of art and not expect the work of art to change for them. Second, our extraordinary times may require us to be and act in extraordinary ways in which the future will judge us.

One regular feature of this novel is its personal warmth and the generosity of the characters in the midst of scarcity—like the simple, scant meals shared by comrades in the struggle. One memorable scene is of corn bread and pork belly, cooked in a fireplace and shared during a terrible, drenching rainstorm. The nearly empty horn of plenty is overcome by the abundance of solidarity. It reminded me of something John Steinbeck wrote about the difference between the rich and poor: If you need a favor, ask a poor person, because a rich one will not give you the time of day.

In terms of plot, as mentioned earlier, this is a sprawling novel. To describe it as epic would not be far off the mark. Still, in aggregate, all the actions of all the characters who create this novel have one focus: how to grow and maintain an effective resistance to the fascist government that captures, tortures, imprisons, and kills its opponents. Thus, beyond the wonderful characters, what most intrigued me were the intrigues, which, if nothing else, should be the pragmatic takeaways from this novel, as they display the methods for successful clandestine resistance to autocratic governments. Keep in mind, however, that these methods need to be updated quite a bit. In the twenty-first century, methods of detection, surveillance, and communication are much more pervasive and, compared to the 1940s, nearly impenetrable and inescapable. Nearly. George Orwell and Ray Bradbury come to mind.

Some questions to ask as you read—and take notes to see how this novel can begin to answer them—include: How do you, indeed how can you work to organize strikes and avoid detection? How do you start and operate a clandestine press at a national level? How do you maintain secure communications between clandestine groups? How do you travel? How do you create safe houses and new or temporary identities for your operatives? How do you finance the movement? And finally, what can any political party do to ensure loyalty?

I hope I am incorrect in saying that it is increasingly important to ask these questions and to begin discussing them because within living memory since the rise of Adolf Hitler, in the persons of Donald Trump, his collaborators, and masses of ignorant and often violent sympathizers, the United States is living in a historical rhyme of 1933. The best short-term response for the resistance movement is to organize. Organize locally, at the state level, and across state borders, and prepare to provide safe houses to your comrades—and read this novel for inspiration.

I have one final, literary comment. In his foreword, Gordon makes one explanation about his translation that I was surprised to read because, on first glance, it seemed unnecessary. He warns that occasionally, but inconsistently, Tiago “leaps into the ‘historical present,’ that is, the use of the present tense in scenes that clearly took place in the past” (xiv). Gordon explains that he retained this usage even if another translator might have tried “to standardize the author’s tenses” to soften the jarring effect the historical present can have for some readers (who would not be aware of the original anyway). I would not deem “standardization of the author’s tenses” in any translation to be true to the work, and I applaud him for foregrounding this bit of our craft for the general reader.

Comments are closed.