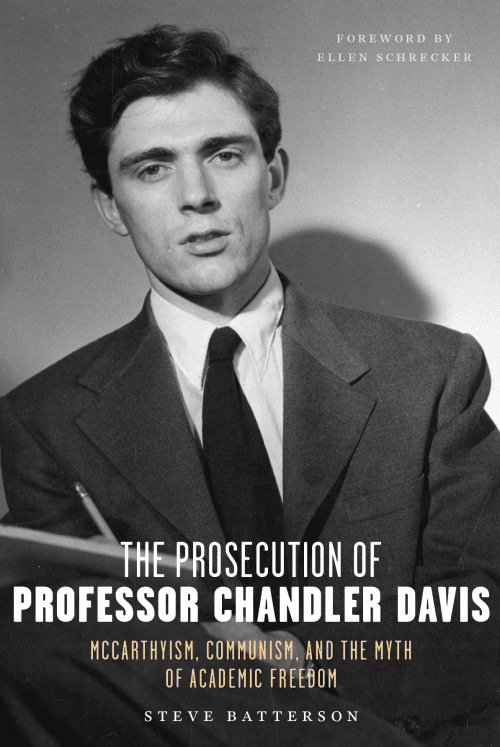

The Prosecution of Professor Chandler Davis:

McCarthyism, Communism, and the Myth of Academic Freedom

By Steve Batterson

200 pages / 978-1-68590-035-9 / $16 paperback

Reviewed by Marjorie Senechal for The Mathematical Intelligencer

“In 2010, fellow mathematician Chandler Davis and I were among a group participating in a hike during a workshop at the Banff International Research Center,” Steve Batterson begins his preface. “I was familiar with Chandler’s 1950’s ordeal with the House Un-American Activities Committee . . . . On the hike, Chandler graciously answered my questions. There was much to his story.”

“Much” puts it mildly. Chandler’s was a cause célèbre of the mid-century inquisition known as the Red Scare. For refusing to answer HUAC’s, and the University of Michigan’s, questions about his past and present political beliefs and affiliations, Chandler was fired by the university, blacklisted at American universities and, in 1960, spent six months in a federal prison. Thirty years later, the University of Michigan’s Senate established the annual Davis, Markert, Nickerson lecture series on Academic and Intellectual Freedom, honoring mathematician Chandler Davis, biologist Clement L. Markert, and pharmacologist Mark Nickerson, the three faculty members it had suspended. But the Davis case differed from the other two in crucial ways, which Batterson exhaustively details.

In refusing to testify before HUAC, Markert and Nickerson had cited the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States (“No person shall be . . . compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself. …”). However, both had testified before a university committee which asked the same questions. Davis, on the other hand, invoked instead the First Amendment (“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech. . . .”) and refused to testify before either. He was fully aware of the possible consequences, as he later explained in “The Purge” [1, p. 421, 422]. “It was predictable that my refusal to answer HUAC, without invocation of the Fifth Amendment, would lead to my indictment for contempt of Congress; indeed, indictment was required in order that I have standing to challenge HUAC’s legality in the courts. . . . I was indicted for contempt of Congress for refusing to answer, and the point was to get the Supreme Court to accept the argument in my defense that the hearing was illegal and so nothing I did at it (cogent or not) could be the basis for a finding of guilt. This challenge was known to be a long shot, and sure enough, I lost and served a 6-month sentence in 1960″…..

Read the rest at The Mathematical Intelligencer

Comments are closed.