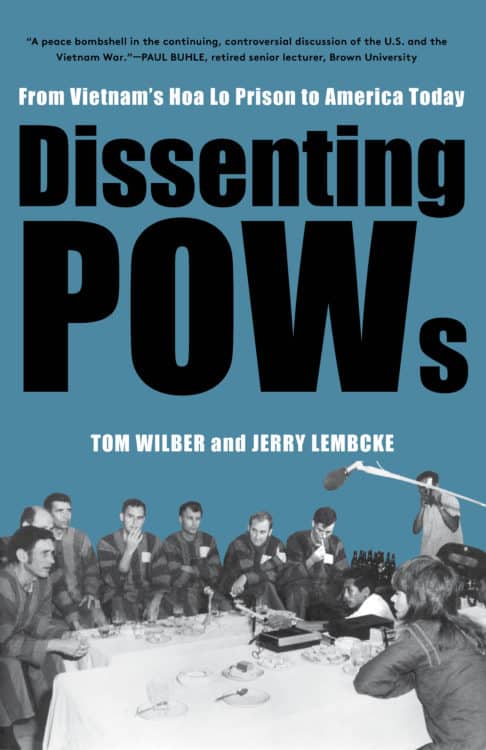

Dissenting POWs:

From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today

160 pages / $19.00 / 978-1-58367-908-1

By Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke

Reviewed by Paul Benedikt Glatz, Jeremy Kuzmarov and Steve Brown

Among the few memories that most Americans still retain of the Vietnam War—now nearly 60 years in the past—one of the most vivid centers around the torture suffered by Senator John McCain at the hands of his brutal Vietnamese captors while a prisoner of war in Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison (AKA The Hanoi Hilton).

This story has been told, retold, and continually burnished countless times by admiring media interviews and a flood of books and memoirs, including several by McCain himself.

Another memory of the war, still believed by millions of Americans, is that hundreds or even thousands of American soldiers classified as MIA (Missing in Action) are actually being held and tortured in secret North Vietnamese POW camps, callously abandoned by our government and desperately praying to be rescued—preferably in a Hollywood-style rescue by Chuck Norris or Sylvester Stallone, who starred in the spate of Commie-hating blockbuster movies inspired by their plight…..

With post-war military careers at stake, these high-ranking officers played up the alleged barbarity of the North Vietnamese, demanded resistance to interrogations from other captives, and threatened so-called deviants with disciplinary charges after release to the U.S.

The Nixon administration advanced their credibility and status in a desperate ploy to stir up support at home for an unpopular conflict abroad; and further concocted a story—announced in a press conference by Defense Secretary Melvin Laird on May 19, 1969—that 1,300 American soldiers deemed “missing in action” were believed to be prisoners of war.

Suddenly, the public image of Vietnam looked very different. The very real footage of brutalized Vietnamese bodies, wailing children, and napalmed villages was traded for a fantasy—all of the violence that had been done in Uncle Sam’s name was now being done to him….

Many U.S. GIs and pilots, however, reported being humanely treated during their captivity, with access to adequate food, recreation facilities and reading material.

Wilber and Lembcke conclude that “instances of brutal treatment” were “less common than [has been] purported” and that evidence of systematic torture drawn from visitor reports, POW statements, and oral histories was scant.

Those POWs who questioned the war were dismissed by the military for their supposedly “weak personal character” and “lack of education and backgrounds in broken and poor families,” a typical case of “psychologizing the political.”

These men were in turn stigmatized and then forgotten by the public amidst the manufactured concern about POW/MIAs who were supposedly brutalized and then kept in captivity and abandoned by their government…..

Empathy for the War’s Victims

Most dissenting POWs came from a working-class background.

James A. Daly, an African-American infantryman from the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, for example, was raised in poverty by a single mother.

His 1975 book, Black Prisoner of War, describes his three years of jungle confinement after his capture by North Vietnamese soldiers and the South Vietnam-based National Liberation Front (NLF), followed by a two-month trek north to Hanoi on the Ho Chi Minh trail where he experienced what it was like to be on the receiving end of U.S. ordnance.

Bob Chenoweth, from a white working-class family in Oregon, similarly developed an empathy for the Vietnamese people and a distaste for the racist views of most Americans toward the Vietnamese.

A helicopter crew member, before he was shot down and captured, Chenoweth said he “couldn’t see how U.S. forces could possibly be helping the Vietnamese given the attitude that GIs had, viewing them as ‘subhuman’ and disparaging them as ‘gooks and dinks.’”

Chenoweth and other of his contemporaries authored anti-war statements, wrote messages to GIs asking them to follow their consciences, sent letters to politicians, and recorded tapes to be aired via Radio Hanoi.

Higher ranking POWs responded by trying to isolate the dissenters from other American prisoners while charging them with participating in a conspiracy against the United States.

One of the dissidents, Abel Kavanaugh, committed suicide as a result of the intense pressure and prospective stigma of a dishonorable discharge only a few months after coming home from Vietnam.

Charges against the POW dissidents were eventually dropped, Wilber and Lembcke believe, so as to not jeopardize the hero-prisoner story with too much attention on dissent and through a possible exposure of inconsistencies in the accusers’ own prison biographies.

Fear of Communist Infiltration

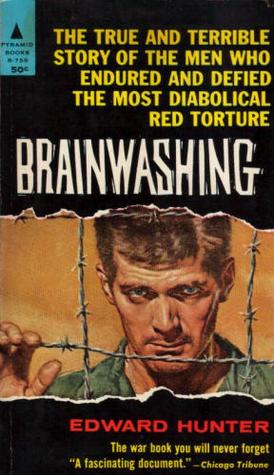

A critical trope in Cold War America was the fear of communist infiltration and internal subversion through brainwashing and mind control.

This trope was fortified by a CIA propaganda effort that depicted Korean War POWs who defected to the North Korean and Chinese side as having been brainwashed in interrogation.

Most of these defectors were in fact African-Americans who did not want to return to the Jim Crow South, while others were attracted by communist ideals or saw the U.S. war as immoral.[1]

The stereotype of the brainwashed POW of the Korean War turned collaborator and traitor because of his weak character would become the backdrop for the discrediting of the dissident POWs of the Vietnam War…..

Hollywood Revisionism

POW films starting from this time focused on returnees’ estrangement with their families and society and were told as stories of spousal infidelity, representing both individual drama as well as a sense of “home-front betrayal.”

These films were part of a post-war revisionism, which included a spate of films that contributed to the legend of American servicemen left behind in Vietnam.

In the 1980s, a new subgenre emerged focused on Vietnam veterans heroically taking on the task of returning to Indochina and liberating the left-behind POWs, who had been betrayed on the home front and abandoned by the U.S. government.

The POWs were depicted as victimized and emasculated captives who needed to be rescued by individualist heroes and whose honor as Americans was to be restored.

This image, Wilber and Lembcke argue, fits the post-war efforts to psychologize the once political conflicts of the Vietnam War and to depict the veteran as a victim and loser.

More of a heroized image and the POWs’ endurance of torture was revived with the 1987 film, The Hanoi Hilton, which starred Michael Moriarty, Ken Wright and Paul Le Mat as U.S. POWs who defy their captors while enduring brutal treatment at Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison (aka The Hanoi Hilton)…..

In addition to some high-ranking officers attempting to portray themselves as heroes by means of self-mutilation, Wilber and Lembcke also noted that they tried to keep political literature and news of dissent back home away from other POWs, fearing that these would enhance critical positions on the war and against their authority within the prison population.

Moreover, these ranking officers often despised the more humane view of the Vietnamese displayed by other prisoners, including an interest in their language and culture, and an understanding of why they were fighting back against an invasion of their country by the most powerful military force in the world.

Bringing Back Forgotten Dissenters

Wilber and Lembcke’s book helps restore these forgotten POW dissenters to their rightful—and honored—place among the large and diverse Vietnam generation of dissidents, draft resisters, oppositional GIs, veteran activists, deserters, and all those who supported them.

To read the full review, head to Covert Action Magazine

Comments are closed.