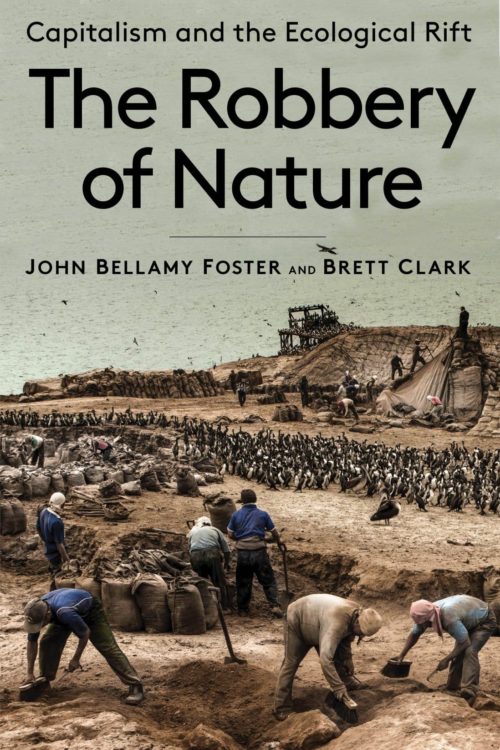

The Robbery of Nature:

Capitalism and the Ecological Rift

John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark

386 pages, 978-1-58367-839-8, $28

Reviewed by Elaine Graham-Leigh for Counterfire

Capitalism, as Marx stated in Capital, is based on the expropriation of the earth. All progress in capitalist agriculture, he pointed out, ‘is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil’ (p.12). John Bellamy Foster established in Marx’s Ecology the centrality of the theory of the metabolic rift created by capitalist production to Marx’s critique of capitalism. The essays here similarly centre on the theme of capitalism’s expropriation of both the natural world and human labour.

That capitalism is based in the expropriation both of nature and of human bodily existence, what Bellamy Foster and Clark call ‘the corporeal rift’ (p.23), is worth restating, as is the point that this is an inherent part of how capitalism works. The capitalist system cannot be reformed out of this tendency to expropriation and ecological destruction. As Murray Bookchin put it, ‘capitalism … can no more be “persuaded” to limit growth than a human being can be “persuaded” to stop breathing’ (p.248).

Recognising this reality gives us two choices. The first is the despairing position which Bellamy Foster and Clark imply is held by most mainstream green thinkers:

‘The implication is that modern Green thinkers, by definition, see ecological devastation as “unconditional” and hence wholly insurmountable, and are inherently pessimistic and apocalyptic, conceiving of no way forward for humanity – at least if this requires a break with the existing social order. This is no doubt an accurate description of the views of most mainstream environmentalists today, who categorically refuse to consider any solution that involves going beyond capitalist relations of production’ (p.34).

The second is, of course, to accept the need to overthrow the capitalist system. This is however not the end of the debate. Some of the sharpest essays here in fact are taking on other revolutionary currents. We may agree on the necessity of replacing capitalism, but what the ecological post-capitalist society could or should look like, and how we might get there, is still in dispute.

Techno-optimism versus green austerity

A particularly interesting example of this debate is the essay dealing with Jacobin magazine’s ‘Earth, Wind and Fire’ issue from 2017, which focused on the climate crisis. In Bellamy Foster and Clark’s view, it did this by ‘[espousing] a techno-optimism in which ecological crises can be solved through a combination of non-carbon energy (including nuclear power), geoengineering, and the construction of a globe-spanning negative-emissions energy infrastructure’ (p.273); imagining that a commodity society could continue, just with the addition of some apparently socialist planning and redistribution.

What the writers in Jacobin are setting out is the Good Anthropocene: the idea that we can accept that human society will continue to shape the natural world, but that we can do it in positive ways. For Bellamy Foster and Clark, though, embracing the Good Anthropocene is simply a failure to appreciate the depth of the social change required. While positioning itself as revolutionary, in their view the Jacobin issue failed to appreciate that ‘revolutionary changes in the existing relations of production are unavoidable’ (p.286). These revolutionary changes will in their view be the ‘long ecological revolution’, which will be brought about by ecological and economic crises and will be fought primarily by the young in the Global South….

You can read the review in full at Counterfire

Comments are closed.