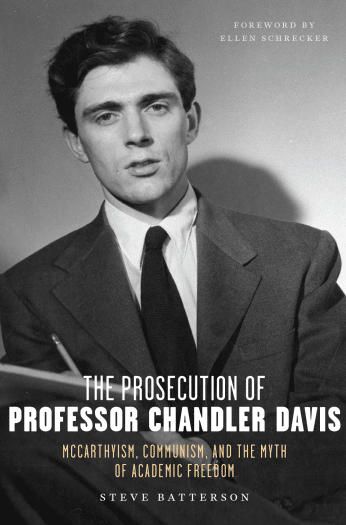

The Prosecution of Professor Chandler Davis: McCarthyism, Communism, and the Myth of Academic Freedom

by Steve Batterson

$16.00 / 200 pages / 978-1-68590-035-9

From the Foreword, by Ellen Schrecker

The American left has few heroes. We specialize in martyrs like Joe Hill, Albert Parsons, and Malcolm X, and masses like the thousands of young women in the 1909 Shirtwaist strike and the Black teenagers who defied the German Shepherds of Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. But we also need to be reminded of those individual heroes who, like Chandler Davis, thrust themselves into history because of their intense commitment to a better world.

In this all-too-timely exploration of Davis’s encounter with McCarthyism during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Steve Batterson shows us how one principled radical managed to stand up against the Cold War witchhunt. Today, as we confront an equally, if not more serious, threat to political dissent and free expression, perhaps Davis’s story can inspire similar resistance to the right’s current attack on our democratic polity.

A radical activist both before and after he was hired to teach mathematics at the University of Michigan in the early 1950s, Chan, as he was called by those who knew him, had been expecting a summons from the witchhunters. When he received his subpoena from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) late in 1953, he already knew that he would not tell its members about his political beliefs and activities. But instead of invoking the Fifth Amendment as so many “unfriendly” witnesses, including his own father the year before, had done in order to avoid prosecution for contempt of Congress, Chan decided to rely on the First Amendment’s protection of free speech and association. He knew that tactic would be a long shot, but he hoped to pressure the Supreme Court to reverse its earlier acquiescence in the Cold War’s Red Scare. As expected, he was not only convicted, serving a six-month sentence in the Danbury Federal Penitentiary, but he was also fired by the University of Michigan and blacklisted by the nearly 150 U.S. mathematics departments to which he applied for a job.For Chan, his legal battle and struggle against the blacklist was part of a lifelong crusade against political repression. Born to a family of rebels that included ancestors on both sides of the Revolutionary War, a family home that was a stop on the Underground Railroad, a great-grandfather who served as a bodyguard to the abolitionist Wendell Phillips and became a war hero after he was wounded at Antietam, and parents who drifted in and out of the Communist Party (CP) during and after the 1930s, Chan’s political activities began in his teens and continued throughout the rest of his life. He joined the CP but did not follow those policies he disagreed with and quietly dropped out a year before his HUAC hearing.

Although punished for his politics, Chan never disavowed his earlier activities or saw himself as a victim. Instead, he viewed his confrontation with HUAC and the following inquisition at the University of Michigan as an opportunity. He willingly risked both his freedom and his career to expose and perhaps even put an end to the mainstream establishment’s willingness to quash left-wing political dissent. That his attempt to convince the Supreme Court to reverse its failure to protect the First Amendment almost succeeded is just one of the surprises that this book reveals. Based on his prodigious research in institutional archives, FBI files, and interviews, Batterson speculates that had Chief Justice Earl Warren not acquiesced in his colleague Felix Frankfurter’s refusal to accept a reference to the First Amendment in the draft of an earlier decision about HUAC, Davis might well have won his case.

Instead, in the Supreme Court’s June 1959 5–4 decision in the case of the former Vassar instructor Lloyd Barenblatt that was to govern Chan’s appeal, Justice John Marshall Harlan based the majority’s opinion on a demonized stereotype of American Communism as a Soviet-led conspiracy to destroy the United States government. For that reason, Harlan explained, the Court “has upheld federal legislation aimed at the Communist problem which in a different context would certainly have raised constitutional issues of the gravest character”…. In short, the Court’s conservative majority assumed, in a flagrant denial of reality, that the small and battered Communist Party posed such a threat to American security that it overrode the Founding Fathers’ commitment to free speech….

Comments are closed.