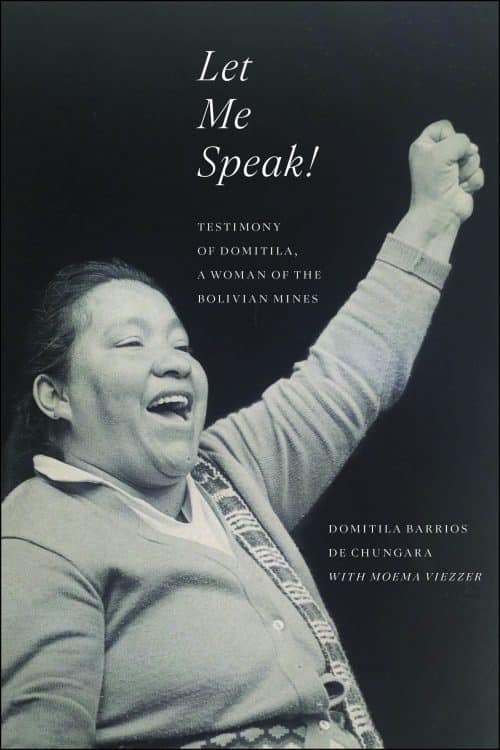

Let Me Speak! Testimony of Domitila, A Woman of the Bolivian Mines, New Edition

by Domitila Barrios de Chungara and Moema Viezzer

352 pages / 978-1-68590-050-2 / $28

From the Preface to the 15th Brazilian edition

by Moema Viezzer

…Today the mine workers and their families are no longer found at the mines, since they have been “relocated” as a consequence of the state-owned company COMIBOL’s denationalization. Now, those former miners and their families are scattered in coca, soybean, sugarcane, and other plantations, when they are not looking for employment or inventing new jobs, or wandering the streets because they cannot find work.

Domitila is one of those thousands of “relocated” people. She now has thirteen grandchildren. Two of her children live in the neighborhood, while the other five are in Sweden, where they settled after their mother’s exile there. Domitila shows some signs of her advancing years and has health problems that make it difficult for her body to keep up with her mind, which is still lucid, and with her heart, which still beats for the cause of her people. Without the support structure that was formerly her arena of action—the Housewives’ Committee of the Siglo XX-Catavi Mine Trade Union, the FSTMB, and the COB—she is now developing her own life project as a social and political educator through the Domitila Mobile School.

In the midst of the countless changes Domitila has gone through—and in spite of them—her objective remains the same. It is like a compass that guides and orients her thought: “I’m loyal to the COB’s political thesis, which is that we need to replace the current society with a new one and that has to be a socialist society.” Now, after going through the adjustments and making so many decisions, Domitila tirelessly repeats her new leitmotif for the context in which she lives: the need for a “popular organization at all levels that extends throughout the country, along with a broad ‘Continent-wide Anti-Neoliberal Front for a Just Society.’”

That is to say, Domitila carries forward the same dreams, the same yearnings, the same desires, and the same commitments, but now in a very different context and in changed conditions….

From the Foreword to the Argentine Edition

By Álvaro García Linera

In addition to telling the history of the working class, the history of nation-building, and the history of Bolivia, Let Me Speak! is also a story about the construction of democracy. Today there are terrible people who might constantly talk about democracy but were delighted when miners died or when Alteños were killed. These people were happily drinking their coffee, while they watched on television how Indigenous people and workers were killed. Now, however, these people like to babble about democracy and the rule of law, despite their never having done anything in the fight for the rule of law or democracy. Domitila’s book serves as an example, a living testimony, of what it means to fight for democracy; that is, democracy not only as the right to vote every five years, but also the right to associate, to think, to organize, and discuss fundamental issues, such as salary, rights, constitutional guarantees, and party politics, in one’s community. This is democracy as a continuous and daily affair, an everyday practice that, much more than the law, much more than the constitutional order, much more than elections, is the ability to intervene in public matters.

Let Me Speak! is also a text of political theory, because you learn here how the miners and workers built democracy, how they were able to fight so that the right to assemble, think, participate, and make decisions would extend to all Bolivians universally. This includes the democracy we enjoy today that allows us to meet here knowing that at the exit to COMIBOL,5 there are no armored cars waiting to take us somewhere where they’ll beat us up. That freedom, which we take for granted today, like breathing air, was not easy to build. It was the workers, hardworking workers, and wives of workers like Domitila who did it. The new generations enjoy all this, but there was a high price paid for it. And it’s important to come back to that. It is important to return to the organizational and social wellsprings of democracy and how democracy is constructed.

Today people are talking about dictatorship. So, to illustrate what the term means, I will read a paragraph of Let Me Speak! It is the year 1967. . . at the Siglo XX mine. . . . Che’s guerrillas are in Bolivia. The Siglo XX mine was the Leningrad of Latin America. . . . The miners lived there, in their little houses made of corrugated tin, with one room or at most two rooms . . . and ten, twelve people per house. Whoever has been to the Siglo XX-Catavi mining complex or to the Caracoles or Central Sud mines knows what the wind and the cold are, the houses there being made of corrugated tin so that the cold doesn’t creep inside. That’s where the miners lived.

At this point in the book, Domitila is accused of having ties to the guerrillas—which she would later have, in the 1970s, but not in the 1960s. The San Juan Massacre has taken place, dozens of miners have been arrested, men and children murdered. They arrest Domitila. She is pregnant, and they want to make her talk. Look at what Moema Viezzer—who redacted the text but keeps herself in the background—recounts with her skillful pen.

You also deserve to be learned from, Moema, with your ability to write, collect, and organize material; not to speak for others, but so that others can speak for themselves. For the younger generation who wants to work with the people, there is a lesson to be learned in how your talent as an intellectual connects with the creative and intellectual capacity of workers. You also have the humility and commitment to place yourself behind and not in front of these workers, so that for example it is Domitila who speaks, not you…

It is not reading the history of a distant country or of some far away moment in time. No, it is the story of what led to our present moment. It’s also a story we don’t have to repeat. We should remember that, thanks to women like Domitila, we can live and go forward in peace today. Thanks to women like Domitila and the social class she represents, today we can read and write without being afraid of being beaten up, disappeared, exiled, killed, or buried.

So this is the history of Bolivia, the real one, the true one, the authentic one—history as it was made by its peoples. It is a story that we have to continue to defend as our own, because what the future brings for Bolivia cannot be the return of the privileged elites, or the story of a few saviors. It has to continue being the story of the people—of ordinary and working people—like Domitila.

Moema, I want to thank you for being with us. I want to thank you for creating this work of art, that is also a work of history, literature, knowledge, and political engagement. I wish there were more Moemas in the world, because I am sure that if there were more writers like her, capable of interacting with the people and telling their true history, the world would be very different.

Please read the book.

Comments are closed.