How the Workers’ Parliaments

Saved the Cuban Revolution:

Reviving Socialism after the

Collapse of the Soviet Union

By Pedro Ross

$27 / 978-1-58367-9784 / 288 pages

From The Introduction, by Chris Remington

The Cuban working class, the Cuban people, the trade unions, the Communist Party and other mass organisations found the solutions to the daily crises and blockade that threatened their very existence. It was not a question of repeating slogans from classic and historic Marxist theoreticians. It was not a question of regurgitating readymade solutions from different eras and different countries. It was about exercising raw power in the workplaces, of applying the distilled history of Cuban revolutionary experience over decades to tackling the issues of the day.

Immensely hard and frank discussions in thousands of meetings in a period of just 45 days in Cuban workplaces addressed collapsed production, absenteeism, critical shortages of electricity, water, fuel, spare parts, transport, and housing. In addition there were the questions of redeploying workers in failed enterprises, corruption and the black market, currency reform, preserving national sovereignty and independence, and upholding the core values of the Revolution—Education, Health, Social Equality.

PART I:

The disappearance of the Soviet Union and the European socialist bloc resulted in a political and ideological crisis with seismic repercussions, devastating for the revolutionary and progressive movement worldwide and in Cuba, mainly in the economic sphere. The situation in which Cuba found itself was like a house painter who suddenly has the ladder pulled out from under him and is left hanging. This abrupt and immense loss of supplies, markets, and sources of finance, along with the worsening of the blockade implemented by the United States, represented a devastating blow. It was inevitable that Cuba would have to urgently adopt measures that demanded great sacrifices, both personal and collective. They would include the postponement of plans and programs for economic and social development. This had to be done to preserve the essential achievements of the Revolution in education, public health, and social security. There was no other way to defend the Revolution’s foundations and to continue to build on them.

Yes, there would be many painfully restrictive measures. But they would not be imposed by government decree, and they certainly would never be neoliberal. They would result from broad and profound consultation with the entire country, including agricultural workers, students, and the general population. The National Assembly of People’s Power adopted this approach, which led to the establishment of the workers’ parliaments during the first months of 1994.

This unprecedented democratic and participatory process produced results that exceeded the most optimistic expectations. It elicited the commitment and the creativity essential to developing feasible proposals for surviving the Special Period. This book will describe how the process unfolded…

THE PREPARATION

The first stage’s preparatory meetings were attended by more than 400,000 union leaders, five for each of the 80,000 grassroots unions…The preparation and development of each workers’ parliament required trade union leaders to assume without hesitation their roles as revolutionary activists and leaders capable of giving opinions, informing, and explaining to the workers the crucial moment that the Revolution was experiencing. In addition, they would consider what should be done in the workplace. What actions could be taken to stimulate discipline and work morale? How can production be increased and improved at lower cost? Where would it be necessary to reorganize personnel? What policy would be followed with the surplus money in circulation? What could be done to reduce or eliminate state subsidies?

…It was a matter of principle that union leaders had the duty to promote the democratic participation of the workers in understanding and solving the problems affecting the functioning of each workplace…A fundamental principle of the workers’ parliaments was that the workers are the owners. Therefore, solutions should be based on labor consensus. Such agreement among workers can advance plans, affirm successful ideas, and confirm the value of what has been thought and decided.

Thus, from the first discussions, the causes of economic inefficiency were examined from each labor center’s perspective. These discussions also tackled the incidence of financial imbalances and offered formulations to combine the economic and the political in the course that the country should follow…

THE WORKERS’ PARLIAMENT AT THE LENIN CENTRAL WORKSHOP

(One of many illustrations)

…That afternoon, we participated in the workers’ parliament at the Lenin Central Workshop, where combine harvester engines for sugarcane were repaired. There, absenteeism was 11 percent. Workers spoke about their efforts to reduce it, noting that a physician who had been providing false medical excuses to workers had been fired from the plant.

We explained to them that the rate of absenteeism from the workshop was equivalent to forty-five days not worked, which, with vacation time, meant that the workshop was productive for only nine months per year. The quality of work at the plant also was a problem. Eleven percent of engines that had been repaired were rejected, rendering useless 204 combine harvesters. As one worker stressed, no one was held accountable.

We noted what those defective repairs meant for the sugarcane harvest. For example, if a UBPC (Basic Unit of Cooperative Production), in which five combine harvesters were used to chop reeds, received only two of those engines, reed chopping would be reduced by 40 percent.

We asked the workers if they felt they could preserve the status of “Labor Exploit” (an honorary award) that they had earned the previous year for having repaired 600 engines in two months. “We are a collective that knows how to do our duty,” they replied, their pride evident. They proposed to put the engines through the test bed to detect and fix any defects. Food for the workers’ cafeteria was another pressing concern. We proposed to create an organoponic garden near the workshop with the redundant employees. An older man vigorously demanded the opportunity to join the agricultural project, despite his age. At the end, solutions to two major problems, food and downsizing, had emerged from our discussion with the workers…

ASSESSMENT TIME: WHAT HAPPENED IN THE PARLIAMENTS?

As the discussion proceeded it became increasingly evident that all the country’s problems were interrelated.

Everyone saw how the parliaments shook up the labor collectives, promoted solutions and palliative measures for many problems, augmented the labor initiatives and the capability of administrative management. The parliaments contributed to the formulation of medium- and long-term national strategies. But we were also aware that the debates themselves would not provide the six million tons of oil we needed, nor could it refund the 75 percent we had lost when imports were abruptly cut off.

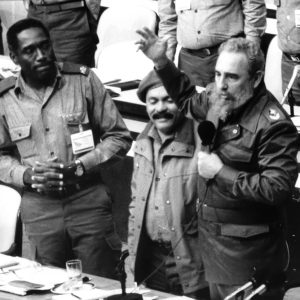

Fidel told us to not think that goodwill was sufficient to solve all our problems. He offered the example of the country’s need to gather a minimum amount of foreign currency. The state, he said, was the sole owner of the shops that sold products at high prices in dollars to recover some needed foreign currency. He noted that some items could not be traded in dollars, like medications, which were lacking because of a misguided initiative by businessmen and not caused by the Ministry of Public Health.

One of the climactic moments of the plenary was the analysis of workplace problems. They were the result of inflated staff rolls, the temporary relocation of workers, the loss of qualified personnel, and the de-bureaucratization of burdensome technical and administrative machinery. That discussion made it evident to all that if these issues were not addressed it would not be possible to achieve economic efficiency or reorganize domestic finances.

The problem, though, was that our depressed and contracted economy reduced our options for a quick reorganization of the Cuban labor army. In this respect, we looked to the experience of the nickel industry, where we identified excess personnel without waiting for the problem to arise in negotiations with foreign capital.

THE INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY OF TRADE UNIONISTS

(Fidel) emphasized that Cuba faced a world totally dominated by and under the hegemony of neoliberal capitalism. We would not surrender but rather had to adapt to those realities, under a blockade imposed by the world’s greatest military and economic power. He observed that because the enemy was working overtime to discourage and demoralize our people, we had to raise their morale and encourage their fighting spirit.

“We have demonstrated what many thought impossible, that after the collapse of the Socialist Bloc and of the Soviet Union, almost four years later, here is Cuba, the country they called [a Russian] satellite, now a heroic star ninety miles from the United States.”

With the dismantling of the USSR and the socialist countries, many trade union organizations lost their referents. The crisis affected not only the former Socialist Bloc but also militant southern European labor organizations: Spain’s Workers’ Commissions (CCOO), Italy’s Italian General Confederation of Labor (CGIL), and France’s CGT. Asian, African, and Latin American organizations that had maintained close links with communist and revolutionary parties also experienced this disorientation.

The United States declared that it won the Cold War, with the supposed triumph of U.S.-style bourgeois democracy proclaimed as “the end of history.” The so-called Washington Consensus entailed brutal neoliberal policies, including the dismantling of historic labor and social achievements and the weakening of trade unions. Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom inflicted severe blows on unionized workers, including the deregulation of labor markets through financial adjustments and the dominance of transnational capital.

For many years, the CTC and Cuban unions were attacked by the CIOSL and mainly by its U.S. subsidiary, the Inter-American Regional Workers Organization (ORIT), which, under the dominance of AFL-CIO, dictated the CIOSL’s anti-communist and pro-imperialist political line.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) was, for many years, the main mechanism by which CIOSL and ORIT orchestrated their campaigns against Cuba and its trade union movement, following the imperial policies dictated from Washington. Despite that, the Cuban Revolution’s international prestige among workers generated sympathy and solidarity with millions of workers, the leadership of their unions to demand reestablished relations with the Cuban people and its workers.

There was no congress or trade union conference anywhere where workers and trade unions did not demand the presence of CTC and its unions, even though they had to defray the costs of our participation. An impressive solidarity and support movement was being forged, in opposition to the interference in Cuba by the United States and the international finance institutions.

During those years, May Day celebrations brought hundreds of thousands of trade union activists and leaders to Cuba, from all over the globe. They would fill our squares to demonstrate their solidarity with Cuba and their condemnation of the U.S. blockade….

PART II:

RECTIFYING ERRORS

The process of rectification of errors and negative tendencies began. Along with the search for solutions to economic problems, ideological and social concerns, Cuba’s youth and the peasantry were scrutinized. The relationship between cooperative farms and state entities also was analyzed.

Fidel insisted that the construction of socialism was not a mechanical process but a political, revolutionary task. The process he was calling for had to be conducted in the midst of a shortage of foreign currency, which had fallen from 1.2 billion dollars to 600 million. There were other pressing concerns: drought had affected sugar production, and Cuban oil export prices fell. Meanwhile, the U.S. economic blockade continued to limit economic growth. All these factors contributed to a 40 percent decline in income.

Cuba, however, was determined to face these challenges without sacrificing its economic or social future. But its model of socialism would have to be rectified. From 1985 to 1990, Cuba entered a new phase in which it had to defend the Revolution’s very existence. The process of correcting ideological, political, and economic problems paid off. In just two years, in Havana alone, 111 kindergartens and twenty-four special education schools were built, as well as twenty polyclinics and 1,600 surgeries staffed by family doctors and nurses. More than 18,000 houses were built by “micro brigades,” a form of workplace organization in which workers left their regular jobs, often for years, to build homes.

The Revolution consolidated the aspirations of the great majority of Cubans. Their sense of ownership of the gains it made fostered perseverance and a tenacity that enabled them to make the sacrifices entailed by the Special Period.

THE REVOLUTION’S SOCIAL INITIATIVES

The Cuban Revolution’s social initiatives focused on education, public health, culture, science, and sports.

After the completion of the adult literacy campaign, Cubans who had become literate were able to continue their studies. In fact, the Revolution made free education available at all levels. The State increased education spending by large increments. More children than ever, from ages six to twelve and thirteen to sixteen, were in school. A national scholarship program was established. Thousands of schools were created, as were training institutes for teachers. The University Reform Law made higher education available to workers and their children while expanding degree programs. The Revolution turned education into a pillar of Cuba’s present and future.

Let’s compare these results with pre-Revolution education data. Nearly one-quarter of Cuba’s population, some one million people, did not know how to read or write. There were 9,000 unemployed teachers; 50 percent of school-age children in the countryside did not attend school, which contributed to high rates of adult illiteracy.

Public health was another priority of the Revolution. Before the Revolution, the infant mortality rate was sixty of every 1,000 live births; today, it is less than five. Life expectancy was fifty-five years; today, it is nearly eighty. In the 1950s, there were only a little more than 6,000 physicians, most of them in Havana. Today, there are 74,000, distributed nationwide. These data are crucial to understanding how profoundly the Revolution transformed this critical sphere.

Public health services, including vaccination, maternal-child care, and preventive medicine, were offered free of charge. Medical services in rural areas were substantially expanded, and the number of hospitals, medical centers, blood banks, polyclinics, stomatology clinics, maternal homes, laboratories, and specialized research centers increased. Given the loss of thousands of doctors who fled the country, encouraged by the U.S. government, the revolutionary government created many medical and nursing schools to train a new corps of health care providers.

From its earliest years, the revolutionary government laid the foundation of a public health system that has won international acclaim—the World Health Organization (WHO) has acknowledged Cuba’s remarkable accomplishments in protecting the health of its people. Not only that, Cuba has altruistically provided medical and health services to people in need worldwide. When COVID-19 struck, Cuba sent health care teams to nearly forty countries to help them cope with the pandemic.

In culture, the Revolution sought to recuperate Cuba’s traditions and reassert its national identity. Great literature was published and reading was promoted. The government established publishing houses, bookshops, museums, theaters, art galleries, and schools….

THE CUBAN REVOLUTION’S FOREIGN POLICY

Ever since the its earliest years, the Cuban Revolution based its foreign policy on alliances with parties, governments, and peoples of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the socialist nations, and on support for the national liberation movements in the Third World. Cuba established relations of mutual respect with nations that acknowledged the island’s sovereignty and independence.

Cuba demonstrated solidarity to national liberation movements in the Third World. This included scholarships for professionals and technicians of developing nations and the assignment of Cuban professionals and technicians, especially in public health, to assist countries experiencing natural disasters. The first such brigade was sent to Algeria in 1963, not long after that nation obtained its independence. Despite the loss of physicians in the early years of the Revolution, Cuba did not hesitate to share its doctors with other nations.

The support offered Africa, a continent with deep historical and cultural ties to the Antilles, stands out. When the Revolution triumphed in 1959, several African countries still were colonies. South Africa’s black and mixed-race people were oppressed by the apartheid system. Cuba supported Algerian patriots in their struggle against French colonialism at the expense of its political and economic relations with France, then still an important power; the shipment of weapons and combatants to defend Algeria from Moroccan aggression.

The tanks sent to Syria between 1973 and 1975 stood guard in the Golan Heights, when that Syrian territory was seized by Israel. Aid to Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese leader assassinated in 1961 by forces linked to the United States and the former colonial power Belgium, after the country gained its independence.118 Four years later, in 1965, Cuban blood was shed in the western zone of Tanganyika Lake,119 where Che, with more than one hundred Cuban instructors, supported the Congolese rebels who fought mercenaries serving the Congolese dictator Mobuto Sese Seko. Cuban instructors trained and supported the combatants of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde, which under the command of Amílcar Cabral, fought for the independence of these Portuguese colonies.

Cuba expressed solidarity with the Vietnamese during the war waged against their country by the United States. Cuban and Latin American blood was shed in Bolivia, where Che Guevara was killed in 1967 under instructions of U.S. agents. In 1981, Cuban construction workers were helping to build an international airport on the Caribbean island of Grenada when the United States invaded under false pretexts. In Nicaragua, Cuban military instructors trained soldiers who were defending the Sandinista revolution in the war of subversion that was organized and armed by the United States….

As Cuba built socialism, it endured aggression that caused enormous human and material losses. The revolutionary government was forced to allocate substantial resources to national defense and security, despite shortages and to the detriment of the country’s development. Successive U.S. administrations have maintained a hostile policy toward Cuba, through terrorism and subversion, and a prolonged economic, financial, and commercial blockade that, for more than half a century, has prevented Cuba from gaining access to sources of finance, equipment, services, and products.

However, Cuba, despite its errors and inefficiencies, has made remarkable progress—political, social, cultural, scientific and technical, and economic….

Comments are closed.