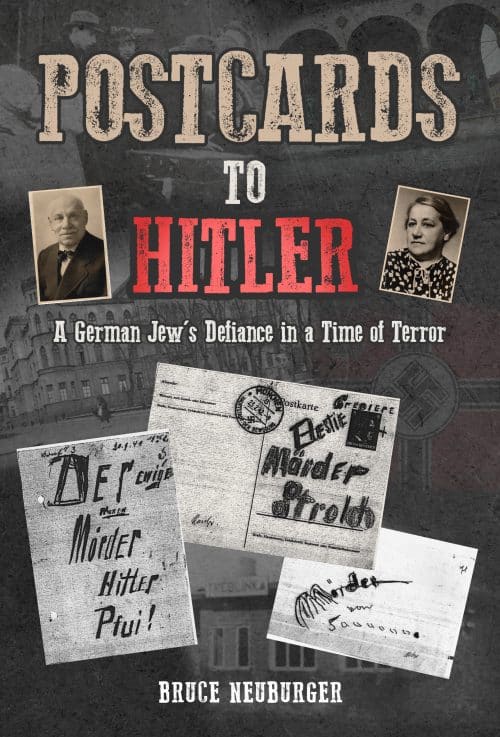

Postcards to Hitler:

A German Jew’s Defiance in a Time of Terror

by Bruce Neuburger

408 pages / 978-1-68590-054-0 / $49

CHAPTER 5: THE 1920S

ONE MORNING, ELEVEN-YEAR-OLD Hani was walking to school with her brother Fritz, then twelve. They were on Thierschstrasse, several blocks from their family’s Liebherrstrasse apartment, when a dog walker wearing a trench coat passed them. Fritz turned to his sister. “You know who that is?”

Hani looked back as the man moved away from them. “No. I’ve seen him before. But I don’t know him.” Hani looked at Fritz with an indifferent expression. “Why should I?”

“His name is Hitler and there are posters of him around announcing his speeches at the beer halls. People come and hear his speeches. And he has a newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter.”

“So?”

“Well, he’s a Jew hater.”

“How do you know that Fritz?”

“They talk about him at school.”

“What do they say about him?”

“Some of the older students like him. Some teachers, too. Well,

they liked the Kaiser, and they want to go back to the old German Reich, before this government now. They hate this German Republic. They say it’s selling out Germany. That’s what I hear a lot of them say.” He stopped to kick a stone. “Anyway they like this Hitler guy because he’s saying those same things. Some of them wear his group’s emblem.”

Hani remained silent.

“You know what I mean, right?” Fritz looked over at his sister. Hani shook her head. “No.”

“It’s a kind of cross.” Fritz stopped walking and took a piece of paper and a pencil from the shoulder bag he was carrying and sketched out a swastika.

“Okay, I’ve seen that. What is it?”

“It’s called a swastika. People at my school who wear it hate Jews.” Hani’s eyes widened. “Do they hate you?”

“No!” Fritz answered emphatically. “I’m a student at the school. I get along with everyone.”

“But you’re a Jew!”

“Okay, but they don’t hate me, they hate the Jews.”

“I don’t get that.”

Fritz shrugged. “I don’t either, exactly.”

“Does it bother you?”

“Of course it bothers me!” Fritz replied sternly. “But I can’t do anything. And it’s just talk”…..

“And what led you to carry out these treasonable actions?”

Benno closed his eyes and remained quiet.

“Speak up!”

Benno breathed deeply. “I don’t regard my actions as treasonable. That was not my intention.”

Eckfellner sat back in his chair behind the desk. “Then what was your intention?”

“To oppose the injustice being done to me—to my family, to my community.”

There was a sneer on Eckfellner’s face. “Your community?”

“To my family. To the Jewish people of Germany. And Europe.”

“An ambitious undertaking.” The interrogator raised his voice. “Your goal was to protect ‘your community’ by insulting the leader of our nation?”

Benno did not try to hide the bitterness in his voice. “To respond to what has been done—is being done to us.”

“Which is?”

“This government has taken our businesses from us, evicted us from our homes and forced my children to emigrate in order to earn a living. We’ve seen our synagogues destroyed, our community organizations disbanded . . .”

“Quiet!” Eckfellner came around his desk and stood over Benno. His tone was threatening. “In these ugly messages you call Hitler ‘a murderer’ and wish for his death. You write treacherous slanders against the leader of our nation!”

“I wrote that because Hitler has repeatedly . . .” Benno hesitated. “Repeatedly threatened to eradicate our entire people.”

Eckfellner looked over at the stenographer. “If Jews continue to align themselves with those waging war against us, they risk . . . grave consequences. I believe that is a more accurate interpretation of our leader’s words.”

Benno looked down at his cuffed hands in front of him. “I know of people in Munich who while gravely ill and in need of medical care were deported, sent east. In other words, they were sent to their deaths.”

“That’s your supposition.”

“My nieces and nephews were sent away months ago.” Benno looked directly at the interrogator. “We have received not one word from them. No doubt they too are dead—murdered most likely.”

“You have no evidence of that,” Eckfellner said sharply. “People are being sent east to be resettled, to start new lives.”

Benno shook his head. “If they were alive, they would have

contacted their parents, at the very least.”

“But you don’t know that. You are only making assumptions. You don’t know where they went or their circumstances.”

Benno did not reply.

Eckfellner glared at his captive. “On this card mailed on January 23, you wrote, ‘Hail the New God of 1933 to 1943.’ What did you mean by that?” When Benno remained quiet Eckfellner leaned forward. “I’ll tell you. Your intent here is to see this government undermined and then violently defeated. Isn’t that so!”

Benno shook his head. “No.”

“By your hateful words you meant to arouse the people to violence against our leader and our government.”

“I meant that the torment and injustice against us, against Jews, must end.”

The interrogator stood up and shouted. “Through force and violence. This is clearly what you intended to provoke.” He then took a drink from a glass of water on his desk and walked out of the room…

CHAPTER 11: MAX HOLZER, 1937

AFTER THE PASSAGE OF THE Nuremberg Laws of 1935 the Nazi press unleashed a campaign warning of the danger posed by Jewish sexual behavior. Julius Streicher’s paper Der Stürmer was the most strident and bloodthirsty. Non-Jewish men were alerted to the dangers their “Aryan women” faced from Jewish men. More “mainstream” and respectable publications also spouted anti-Jewish hype. Non-Jewish women, “Aryan” women, were warned to beware of Jewish men.

Attacks on Jewish men by the legal system rose sharply. In 1936, 358 people were prosecuted for sexual crimes, a huge jump from the previous year. In 1937, this increased to 512. Two-thirds of those arrested and tried were Jewish men, even while Jews made up fewer than 1 percent of the population. The mainstream Nazi papers sensationalized trials of Jewish men accused of improper sexual behavior with German women.

The definition of illicit sexual relations was extended to cover nearly any kind of bodily contact between Jews and non-Jewish Germans. Under pressure from the Gestapo and the Reich Justice Ministry, those found guilty of sexual crimes, or “racial defilement,” were sentenced to ever longer terms of imprisonment in penitentiaries—not just ordinary prisons.

Some Germans took advantage of the legal leverage this provided them. Businessmen threatened or arranged for Jews, including those involved in commercial competition with them, to be arrested on false charges of “racial defilement” in order to extort concessions and bribes from Jews.

Attacks on Jewish men were a potent weapon for the Nazis. Because many Germans had no contact whatsoever with Jewish people, it was easy to paint a bleak picture of them. The incessant warning that Jewish men were a threat to non-Jewish or “Aryan” women aroused German men’s hostility to Jews while appealing to their masculinity. It reinforced both patriarchy and misogyny as it implied that German women were weak and easily seduced by oversexed and lecherous Jewish men. The Nazis emulated the mindset that prompted the lynching of Black men in Jim Crow America. As Der Stürmer advised its readers, “This is how racially conscious men in America act: They lynch any Negro who even attempts to defile a girl of the white race.”

On November 26, 1937, Traunstein police accompanied by a Gestapo agent arrived at 6 Kernstrasse and demanded to see Max Holzer, the youngest son of Anna’s sister Fanny.20 This was not good news and Max’s first impulse was to leave the house. But he came to the door, and the uniformed men, one of them a well-known member of the town’s Nazi group, told him he was being arrested.

“What is this about?”

“You’ll find out soon enough,” the Gestapo man snapped.

At the police station, Max was told by one of the arresting officers that he was being charged with sex crimes. The officer said a number of women had denounced him, but he didn’t say their names. Later, a police arrest order revealed the names of several gentile women who had worked as housekeepers in the Holzer home. They had claimed that Max had sexually molested them. Max was taken into custody and held in the Traunstein jail where he remained until his trial three months later.

The shock of Max’s arrest hit his family very hard and sent them scrambling to find a lawyer. They were able to locate one in Nuremberg who was one of the few Jewish lawyers still allowed to practice, apparently because he was a war veteran.

Fritz was in Prague on business in January 1938 when an article in a local paper caught his eye. He saw the name of his cousin Max Holzer in a headline. He saw the word Traunstein as he skimmed the article. He knew of the trial but was still stunned to read that Max had been convicted and sentenced to five years in a German penitentiary—five years for this feisty cousin he’d known since childhood. He got an extra copy of the article and sent it to his sister Hani in the United States. He hoped Hani could use the article to impress upon Jews in the United States, many of whom were not taking the situation in Germany that seriously, just how dangerous Germany was becoming.

When Fritz returned to Munich a few days later, he found his cousins Klara and Alfred—Max’s siblings—and Alfred’s wife, Martha, at the Trogerstrasse apartment. “We felt we had to tell your parents about Max, and we didn’t want to talk about it on the phone,” said Klara. “Papa is very distraught and we’re all going crazy trying to figure out what to do.” They had brought with them a copy of the local paper, the Traunsteiner, with a front-page article on the trial. Alfred and Martha sat at the dining room table with Fritz while Klara stood nervously next to her cousin. She read aloud a section in the article where the writer stated he was including details of the trial “in order to inform the public which has not always kept the necessary distance from the accused.”

“This is what this is all about,” Alfred exclaimed, responding to the words of the article. “We really already knew that, but here it is in print. This is what they’ve been trying to do for four years—isolate us from our neighbors, especially the farmers we do business with.”

“The Nazis in Traunstein weren’t able to turn people against us,” Klara threw the paper on the dining room table. “Now, this is having more effect. Since Max was arrested, we’ve had farmers turn away from us. We’re having trouble getting some of them to pay what they owe us. One farmer, who has always been friendly and supportive, said to me the other day, ‘Maybe I have been wrong about you people’!”

“It’s right here.” Alfred pointed to the article. “‘Every German-thinking businessman should take note when considering trade with the Holzers.’”

Fritz took the paper from his cousin. He shook his head as he read the first paragraphs of the article: “‘In Central America, in Martinique, there is a dance among the Blacks there, the Biguine, a strange obscene midnight ritual performed in secrecy.’ Odd, no?” he said.

“In the first place the writer knows nothing about geography.” Martha, normally easygoing, was now bitterly sarcastic. “For starters, Martinique isn’t in Central America—it’s several thousand kilometers away in the Caribbean!”

Fritz looked from Martha to Alfred, “Martinique?”

Alfred struck the table with the palm of his hand. “Here’s the way I understand this. The writer is saying to the Traunstein readership, ‘You think you know Max Holzer as that happy-go-lucky fellow who grew up in your town and always had a joke or funny comment. No. No. The real Max, the Jewish Max, is like one of those dark people on this strange jungle island who engage in obscene sexual practices.’….

CHAPTER 16: SHATTERED GLASS

…Zindel and Rivka Grynszpan were among the deportees. They had lived in Hanover, Germany, for twenty-seven years where they ran a small tailor shop. After their sudden deportation, their daughter Berta wrote a desperate note to her seventeen-year-old brother living in Paris. “Herschel, we haven’t got a penny.” She implored him to send whatever he could. Tormented by his family’s trauma and his inability to help them, Herschel bought a pistol and on November 7 headed to the German Consulate in Paris intending to kill the German ambassador. Informed that the ambassador was out, he was sent to the office of Ernst vom Rath, a minor consular official. There Grynszpan pulled his pistol and shot vom Rath in the stomach.

The top Nazi leadership was gathered in Munich on November 9 for the annual commemoration of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler spoke at the Burgerbraukeller, and later that evening he was at a dinner in Munich’s city hall when word came that the German consular official Vom Rath had died of his wounds. After consulting with Hitler about Vom Rath’s death, Joseph Goebbels rose to make an impromptu speech. In remarks filled with violent vitriol against Jews he threatened violent retribution for the killing of a “loyal servant of the Reich.” Goebbels noted in his diary that his speech was received with “thunderous applause. All are instantly at the phones. Now people will act.”

Following Goebbels’s speech, the Nazi officials gathered from around the country called their local offices to inform them of the death and instruct them to attack Jewish businesses, synagogues, and other institutions. They were told to make the assaults look as much as possible like spontaneous responses from an outraged public. Care was to be taken to make sure that non-Jewish properties were not damaged in the rampage.

A March to 6 Kernstrasse

The Nazis in Traunstein were having their own celebration of the Putsch anniversary on the night of November 9 when the call came in from Munich. As instructed, some uniformed marchers went home and changed into civilian clothes. Then, about forty marchers, led by their leader, Franz Werr, and the town’s vice mayor, Albert Aichner, marched to the Holzer family home. As they neared the Kernstrasse house, they began shouting, “Jews out of Traunstein!” “Holzers out!” Several pulled pistols and began firing into the house. Some of the men broke down the door and began trashing the house. A member of the family who was there at the time heard some of them shouting, “Where’s that bitch who was in Paris?”

The oldest son, Benno, was upstairs when the Nazis broke in. He escaped the house by crawling out of an upper-story window and onto the roof. After running from the property, he found refuge with a family who owned a small bakery near their home.

Willi Holzer, his son Alfred, his daughter-in-law Martha, his daughter Hedi, and a family with two young children who were visiting from the nearby town of Freilassing were taken into custody by the Traunstein police. In the brutal home invasion, Martha suffered a severe injury to her foot and later had to be hospitalized.

Louis Holzer’s daughter Hansi, her husband, Paul Lowy, and their daughter Margaret were also visiting Traunstein at the time. That family had previously fled their home and business in Salzburg, Austria, after the Nazis took over the country in March 1938. Frustrated at not finding some of the family members they were looking for, the Nazis held fourteen-year-old Margaret Lowy captive for “questioning.” They held her all night—a horrific night that changed her life forever.

A Fire in Judenberg

On the night of November 10, Nazis from Laupheim and other nearby towns descended on Judenberg, Laupheim’s Jewish quarter. They went door to door demanding that Jewish residents leave their homes. They pounded on the door of the house at 49 Kapellenstrasse and shouted, “Out or we’ll break down your fucking door!” Anna’s sister Mina Einstein and her housemate Sofie Braunge thought to hide, but then realized they had no choice but to surrender. Once out of the house, the Nazis shoved the two older women into the street. Then, they marched all the Jews from the neighborhood to the synagogue and ordered them to kneel in front of the temple. The Nazis, whipped into a violent frenzy, broke into the temple, and spread gasoline in the pews and over the aron hakodesh, the cabinet which holds the Torah.

While Mina, Sofie, and the other Jewish residents knelt in front of the synagogue, one of the Nazis threw a match onto the gasoline-soaked floor of the building. As the synagogue burned, Judenberg’s residents were ordered to shout, “We are burning the synagogue! We are burning the synagogue!” Mina and other Judenberg residents cried bitterly as they watched the building that was so central to the life of their close-knit community burn to ashes.

Anti- Jewish Measure

November 8, 1938

The German government announces that all Jewish newspapers and magazines are to immediately cease publication. The order affects three Jewish newspapers with national circulation as well as four cultural papers, several sports papers, and several dozen community bulletins. Only one Jewish publication, the Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt (Jewish Newsletter), is allowed to continue to publish so as to inform the Jewish community of the measures being imposed on them.

Anti-Jewish Measure

November 10, 1938

Hitler meets with Reich Propaganda Minister Goebbels at the Osteria Bavaria in Munich to finalize a draft of a decree to bring the pogrom to an end. They discuss ways to deny insurance compensation for Jews while speeding up the expropriation of Jewish businesses.

Anti-Jewish Measure

November 10, 1938

Heinrich Himmler, head of the Nazi SS, declares that any Jew found to possess a gun will serve twenty years in prison.

A Pistol in Wolfratshausen

Early in 1938, Hermann Spatz, husband of Tilli Holzer, and his son, Wilhelm, moved from their home in Wolfratshausen to an apartment at 12 Landsbergerstrasse in Munich. On the night of November 10, Hermann heard of Himmler’s threat to imprison any Jew found with a gun. Fearing that his house in Wolfratshausen would be raided and the police would find an old war pistol he kept there, he returned to his old house to retrieve the weapon and hide or dispose of it.

The next day, he was caught on a street near his house and sent to the Dachau concentration camp. At Dachau he was badly beaten and forced to agree to sell his Wolfratshausen home for well under its value to a Nazi who worked at the camp. The money from the sale was placed in a blocked bank account, and the war veteran thereafter had to ask permission to retrieve meager funds from the forced sale of his property.

Carpets of Glass

Just before midnight on November 9, a display window at a Jewish textile shop in Munich was set on fire. Within minutes Ohel Jakob, the only large synagogue remaining in Munich, was also in flames.

In the early morning hours of November 10, groups of Nazi SA and SS members in civilian clothes took clubs and crowbars and smashed the windows and doors of Jewish businesses on Munich’s Kaufingerstrasse. They entered the shops, removed the displayed products, and threw them in the street. They stole, stomped on, and urinated on merchandise. Some Munich streets were left littered with debris and carpets of glass. By the end of the night every Jewish shop in Munich was partly or completely wrecked. Munich’s fashionable street looked as though it had been bombed.

On the morning of November 11, nearly every non-Jewish shop in Munich bore a sign that said: “No Jews Allowed.”

Dachau

On November 10, a memo was sent to the Dachau concentration camp to prepare to receive 10,000 new prisoners. That same evening a police van pulled up in front of 44 Trogerstrasse. Munich Police and Gestapo agents pushed their way into Benno and Anna’s apartment and took Benno into custody. Benno was driven to a train station filled with heavily armed police and hundreds of other Jewish men from the Munich area.

The train carrying Munich’s Jewish men arrived late at night at Dachau. En route, the passengers had to remove their normal clothes and don thin cotton uniforms and ill-fitting shoes. As they walked from the train station to the concentration camp Benno saw the rows of wooden barracks surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers. These had replaced the munitions depot where he’d served during the war.

Benno was one of 500 Jewish men from Munich brought to Dachau that day. He was one of 30,000 Jewish men arrested and sent to concentration camps across Germany during what became known as the “Kristallnacht Pogrom” or the “Night of Broken Glass.”

On November 11 Munich’s mayor, Adolf Wagner, spoke to a crowd of 5,000 at the Munich circus denouncing Jews, Catholics, and the Pope, who had spoken out against the Kristallnacht violence. Following Wagner’s speech, a mob attacked the Catholic cardinal’s palace, smashing windows and cursing Munich’s Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber. The previous day Faulhaber had responded to a plea for help from the rabbi of the Ohel Jakob synagogue by sending a truck to rescue religious objects from the temple before it was destroyed. The attack on von Faulhaber’s home was retribution for this small act of kindness to the Jewish community.

Dread in Queens, New York

Hani had just gotten back to her Astoria apartment from her job in Manhattan and was in the kitchen when Fritz came in. “How’s the new job at Klein’s, Fred?” Hani asked as she took a plate of leftover chicken out of the small Hotpoint icebox. Fritz’s new American name, “Fred,” still sounded strange to Hani, and she had to be careful not to slip back into “Fritz,” his German name. She was about to comment on this but stopped when she saw her brother’s anxious look.

Fred put a copy of the November 11 issue of the New York Daily News on the kitchen table and sat down. “Hani you have to look at this.” Hani sat down next to her brother. “Oh my God!! My God!!” Her face reddened and she broke down in tears. “Ludwig is visiting his sister. I’m going to call him.” Hani hurried into her bedroom. Fred heard his sister’s quavering voice while she spoke on the phone with her husband. After several minutes Hani came back to the kitchen. Her eyes were bloodshot, but she was no longer crying. “Ludwig will be here soon.”

When Ludwig entered the apartment he didn’t take off his coat or hat. He sat down at the kitchen table and looked down at the paper Fred had spread open. Hani cleared off a few dishes so the paper could lay flat. The three of them stared at the paper with its large headline: “Nazi Mobs in Orgy of Anti-Semitism Wreck, Burn, Slay.” Ludwig read aloud sections of one article, translating parts as best he could from the English for his wife and brother-in-law: “Synagogues have been burned. Stores have been destroyed and looted. Ten thousand stores in ruins. Many suicides . . .” Hani gasped at each sentence. Fred was quiet but tears filled his eyes. He tried to wipe them away without drawing notice.

Ludwig had a soft, high-pitched voice that matched his thin build. But his distress and anger expressed itself in a loud, agitated quality as he read from a long list of atrocities enumerated in the Daily News article. He paused. “And here”—Ludwig pointed to a section of the article—“this is some real bullshit!”

“What do you mean?” Fred looked down at the paper.

“It says here, ‘The mob paid no heed to Goebbels’s order to stop the destruction.’”

“Ach!” Fred got up and paced the small kitchen. “Goebbels tried to stop this!? We’re to believe that the chief arsonist tried to put out the fire!” For a moment he thought about picking up a plate and smashing it against the wall. “We’ve got to get our parents out!”

The phone rang and Hani went into the bedroom to answer it. When she returned to the kitchen, she said, “Fritz, it’s our cousin Ida from Chicago, why don’t you talk to her. I mean, Fred . . .”

When Fred returned from the bedroom, he said, “Ida’s in shock.” He looked at his sister. “She hadn’t taken the situation very seriously. But she sees it now. She just heard a radio report that thousands of Jewish men have been taken to the camps!”

“Who is Ida?” Ludwig asked.

“She’s the daughter of our Uncle Markus—Dad’s brother,” said Hani. “She lives in Chicago.”

Ludwig picked up the newspaper, his voice still shaking as he read and translated, “Gangs entering houses, breaking down doors of Jews and dragging them out.”

Fred looked intently at his sister. “Ida says she knows a politician in Chicago, a Mr. Sabath. She’s going to try and see him. Getting the affidavits is not going to be the most difficult issue. It’s the visas to enter this country—that’s what we have to work on. So this contact of Ida’s might help.”

“This government could do a lot more than it has. It shouldn’t be so hard for us to get visas,” Ludwig fumed. “Capitalist governments don’t give a damn about you unless they can get something out of you. This country’s no different than any of them.”

“I don’t feel quite as negative about it, Ludwig.” Fred stood up again. “We should write a letter to Munich right now, Hani. We have to be careful what we say, but we should let them know we understand the seriousness. And tell them about Ida’s new resolve.” Fred pulled the writing paper they used for international letters from a drawer and he and Hani began to compose a letter.

At about the same time, Anna was writing a carefully neutral letter to her children.

November 12, 1938

Dear Hani and Fred,

We have received your letter from November 4. We are happy that you children are doing so well. As to myself everything is the same. I’m alone but Dad will be getting home soon. Louis and Willi just came by.

‘Don’t worry about me—under these circumstances, I’m just fine. My dearest wish is just to be with you and Dad of course as well. That’s all we are thinking about but when will it happen?

Your mother.

Anti-Jewish Measures

November 12, 1938

Head of the Nazi four-year economic plan, Herman Goering, convenes a conference at the Berlin Air Ministry. He rages at the assembled economic and domestic affairs functionaries over the losses Germany suffered in the November pogrom, such as the glass that had to be imported to replace shattered windows in Jewish businesses, the insurance claims that had to be paid to Jewish insurance holders to protect the insurance industry’s credibility, the economic loss as a result of goods stolen or destroyed from wrecked Jewish stores, and the loss of tax revenue from businesses put out of action. He demands measures to mitigate these losses. The conference comes up with policies to soften the blow to the German economy. Chief among these is a plan to confiscate Jewish insurance claims and impose a collective fine on the Jewish community of a billion Reichmarks (the equivalent of about 5 billion 2023 dollars) for the damage the nation sustained during the pogrom….

TO READ THE REST, GET YOUR COPY HERE

ALSO, SEE THIS VIDEO

Comments are closed.