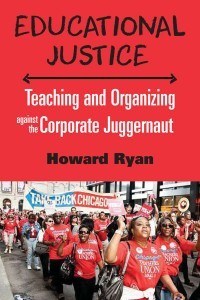

Educational Justice: Teaching and Organizing Against the Corporate Juggernaut

287 pp; $23 pbk; ISBN 9781583676134

By Howard Ryan

Reviewed by Patrick Yarker for Forum (a journal covering UK government policy regarding the education of children from primary through higher education), Volume 60 Number 3 2018

“Teachers in the US have been walking out. West Virginia, a state with a proud history of industrial militancy, saw two weeks of unofficial strike action in the spring. Strikes followed in Oklahoma, Kentucky, North Carolina, Colorado and Arizona, all states which return Republican legislatures and voted for Trump. After years of cutbacks imposed on ideological grounds to state-funded services, teachers built for action, took it, and won increased public-service budgets and higher pay.

Wide-scale walk-outs in states, and more localised action in cities such as San Diego, Los Angeles and Chicago, have for the most part been organised outwith the established structures of teacher unions. Too often those unions are unrepresented at school district level, and can provide only a token lobbying presence at state level. In such circumstances payment of union dues becomes an unappealing proposition for cash-strapped practitioners. But the main driver of militant rank-and-file action has been the failure of the established union leaderships to fight on behalf of the membership. Leaders of the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Education Association, the two large national bodies, accepted links between teacher evaluation and student test scores, and so cleared the way for payment by results. This decision opened a gulf between members and high officials. Other concessions around issues of job security, the spread of charter schools, and school closures, widened that gulf. An approach to negotiation built on ‘conceding not leading’ (as it is termed in Howard Ryan’s book) demoralises union members and makes it harder to convince non-members to join.

Where union leadership is weak or compliant in the face of sustained attacks on the funding of public education and on teachers’ pay and conditions, activists have looked to forge other networks. Howard Ryan explores the two big questions this raises, namely what does the union stand for, and how is the union to be led? His book presents detailed narratives of grass-roots victories, along with an explicitly class-based analysis of the broader context in which these have been won. Ryan understands this context as shaped by the ‘corporate occupation’ (p. 10) of education in schools, which he characterises as an ‘assault’ (p. 12). Many of these corporate-driven ‘reforms’ will be familiar to teachers in the UK. They include: an externally-imposed ‘standards’ agenda drawn up without the participation of those most affected; the spread of high stakes testing along with a drive to raise attainment by data-driven teaching; the restructuring of educational services in ways which facilitate privatisation; and further weakening of education workers’ job security and professional voice.

Ryan and his co-contributors explore the way the dynamic interaction of school and community can bolster working-class students against a pervasive deficit-model which asserts they cannot succeed and which helps reproduce existing inequalities. ‘Public education’, Ryan notes, ‘is fundamentally about democracy, equipping young people with skills for effective citizenship and participation’ (p. 16). One essential aim of the currently-dominant policies has been, he claims, ‘to squelch democracy by converting schools into centres of obedience training for working-class youth.’ (p. 18)

In opposing such ‘reform’, teachers find they must also work to democratise their union, so that it becomes an instrument which serves this necessary opposition. Where members organise and mobilise, they can create new conditions and make gains. Several chapters in the book offer case-studies in which such an approach has borne fruit, if only temporarily, for individual schools and their communities. We learn how teachers at the Jacob Beidler Elementary School in Chicago successfully fought off incorporation into a charter school. Incorporation would have handed public assets to the private company running the new school, forced students to travel across gang-territory to be educated in an unfamiliar setting, and made teachers re-apply for jobs with no guarantee they would again be hired. Elsewhere in the city a principal’s bullying and budget-cutting was successfully resisted thanks to local union leaders who took a stand, and then organised on the ground, kept members fully informed, held regular accessible meetings, and told the truth about the situation to teachers, governors and parents.

Ryan advocates school-based community organising as a way to amplify the power teachers and parents/carers can wield. Social injustices confronting a local community will arrive, sooner or later, inside the school which serves that community. Teachers’ unions can collaborate with community organisations to mobilize against harmful policies. Ryan further argues the necessity for teacher unions to involve themselves sustainedly in debates over curriculum. This must also mean debates about pedagogy and assessment. Two case studies set in Los Angeles show teachers collaborating to make best use of whatever agency they retain within their settings in order to offer ‘living alternatives’ to what has been termed ‘the pedagogy of poverty’ (p. 208). This consists of a regimented drill-based approach to teaching, in particular the teaching of reading, which corporate reformers see as necessary to administer to children from impoverished backgrounds, on whom generosity of provision and creative pedagogical approaches need not be wasted.

Debra Goodman’s chapter about the ‘whole language’ movement is especially pertinent. Goodman’s parents helped inaugurate ‘whole language’ approaches to the teaching and learning of what is now, perhaps all too readily, termed ‘literacy’. She values that movement not only for its efficacy in helping children learn to read and write, but also because it empowers practitioners and enables them to support each other beyond their own workplaces, for example by joining dedicated networks which have a nationwide span.

‘Whole language’ approaches recognise individual learners as makers of meaning, and encourage them to relate what they already know of text and the world to the new materials encountered in school. As the drive to streamline the teaching of ‘literacy’ has taken hold, the idea of meaning as complex, contestable and constructed has been supplanted by a view which sees meaning as singular, pre-existent in the text only, and always readily available to be found. This in turn has licensed the use of simplistic right/wrong testing as a way to gauge reading ‘competence’ and development. Goodman is surely right to conclude that ‘… discussion of language pedagogy remains extremely critical today, in an era when reading-evaluated through high stakes tests-is a focal point in corporate attacks on teachers and public schools.’ (p. 185).

…

The US teachers’ walk-outs, appearing to come out of nowhere, surprised the leadership of the unions as much as the employers. But such action is never conjured out of thin air. It arrives because people prepare it, laying the ground patiently in the seemingly-quiescent periods and in the times of defeat.

Even so, preparation and militancy, though essential, don’t guarantee success. In Oklahoma and Kentucky, union leaders cut a poor settlement to end the dispute over the heads of those teachers who took action. Gains in one school, or in a city, or even across a state, can only be provisional absent wider changes in the political field. Hence the need for a vision of society which will consolidate and build from such gains, as Howard Ryan articulates….”

A fuller consideration of Ryan’s book can be found at Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies. (Subscription needed.)

Comments are closed.