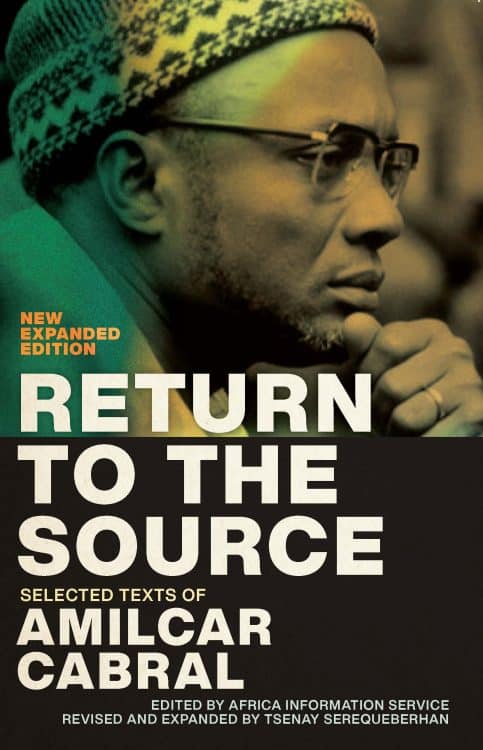

Return to the Source:

Selected Texts of Amilcar Cabral, New Expanded Edition

By Amilcar Cabral

Edited by Tsenay Serequeberhan

296 pages / $20 / 978-1-68590-004-5

Reviewed by Dominic Alexander for Counterfire

The era of the great leaders of the national liberation movements of Africa, like Cabral, Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba, is long over, and with the ANC losing its majority in the South African elections, disillusionment with the heirs of the era of national liberation seems complete. The failures of post-colonial African polities and economies have not, however, dimmed admiration for the original generation of leaders, and since imperialism can rightly be blamed for the systemic problems of African countries, this is not surprising. The fact that many of the liberation movements were sabotaged by assassination, coups or other means, most likely through the active machinations of US imperialism, only adds to the lustre of the great figures of the liberation era. Many believe Cabral’s assassination was at least orchestrated by Portuguese colonial authorities (p.16).

Amilcar Cabral was the leader of the national liberation movement in Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands, and was assassinated in 1973, months before Guinea-Bissau was able to declare independence. Like many others at the time, Cabral was strongly influenced by Marxism, although he also declined the label when questioned about it, arguing ‘I am a freedom fighter for my country. You must judge me from what I do in practice … But the labels are your affair … Just ask me … Are we really liberating our people, from all forms of oppression?’ (p.38). His answer to the question about the relevance of Marxism and Leninism to the struggle in Guinea-Bissau was admirably materialist and dialectical: ‘Moving from the realities of one’s own country towards the creation of an ideology from one’s struggle doesn’t imply that one has pretension to be a Marx or Lenin … but is simply a necessary part of the struggle … We needed to know them, as I’ve said, in order to judge in what measure we could borrow from their experience to help our situation’ (p.37). So, Cabral was thinking and doing with Marxism, adapting what he could within the particular material and historical position of a notably undeveloped African society.

The anti-colonial struggle in Guinea and the Cape Verde islands, under Portuguese rule, was not, for Cabral, a simple matter of removing colonial rule. His comments on Portugal assume a world system within which national liberation movements had to operate. In a speech to the 1965 Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP), he made a distinction between colonialism as such and a wider system of imperialism: ‘We are for the complete liberation of the African continent from the colonial yoke, for we know that colonialism is an instrument of imperialism … we are fiercely opposed to neocolonialism, whatever its form’ (p.68). Cabral was under no illusion that removing Portuguese rule would eliminate imperialism itself.

Imperialism within imperialism

On Portugal specifically, Cabral noted its place within the wider imperialist system. Its own underdevelopment meant that it was fighting hard to resist granting its colonies independence: ‘we can say that independence was given to colonized countries by the colonial powers as a means of securing the indirect domination of colonized peoples. But Portugal does not possess the economic infrastructure that will allow her to try decolonization in this manner. She cannot decolonize because she cannot neocolonize’. Indeed, Portugal stands in a clearly inferior position to wider imperialism: ‘Portugal herself is a semi-colony. Even the telephones in Portugal are not of Portuguese manufacture, nor the tramways, nor the railways’ (p.25, and similarly pp.143-4).

It was this situation which led to the outbreak of armed struggle against Portugal, because the intransigence of Portuguese colonialists meant ‘that we had to try and force them to change’ (p.26). In a talk to black Americans in 1972, he elaborated further that ‘Portugal would never be able to launch three colonial wars [Guinea, Angola and Mozambique] in Africa without the help of NATO, the weapons of NATO, the planes of NATO, the bombs of NATO – it would be impossible for them’ (p.143). Elsewhere, he notes that the liberation movement had captured many US weapons in the war (p.72). Formally, Nato’s first out-of-area war was against Serbia in the Kosovo war in 1999, but its role as a bulwark of Western imperialism in the world in general was significant long before.

Cabral was primarily, of course, a nationalist leader, and his priority was the practicalities of the liberation of Guinea and the Cape Verde islands, but even apart from his qualified support for Pan-Africanism, which was on the condition that African unity would not ‘forget the interests of the world, of all humanity’, there was nothing narrow about his nationalism. In an address to the United Nations, he declared that ‘my people are more convinced than ever that the struggle being waged in Guinea and Cape Verde and the complete liberation of that territory will be in the best interests of the people of Portugal’ (p.57).

In case this seems likely to be a piece of diplomacy more than anything else, in the same speech to CONCP quoted above, he also said that ‘The enemy is not the Portuguese people, nor even Portugal itself: For us, fighting for the freedom of the Portuguese colonies, the enemy is Portuguese colonialism, represented by the colonial-fascist government of Portugal.’ He attributes the violence of Portuguese colonialism to the underdevelopment of the country itself, which ‘you will find at the bottom of all the statistical tables of Europe. This is not the fault of the Portuguese people’ (p.67). Moreover, the problem is that the people of Portugal ‘who have not even enjoyed the wealth taken from African people by Portuguese colonialism’ have ‘assimilated the imperial mentality of the country’s ruling classes’ (p.89). Imperialism appears in this register as a problem of class, rather than countries or their peoples.

Repeatedly in these speeches and articles, he insists that ‘we do not see a link between skin colour and exploitation’ (p.11). And further that ‘we are not fighting simply in order to hoist a flag in our countries …[but] so that our peoples may never more be exploited by imperialists – not only by Europeans, not only by people with white skin, because we do not confuse exploitation or exploiters with the color of men’s skins; we do not want any exploitation in our countries, not even by Black people’ (p.68). Cabral was a socialist as much as, or perhaps even more than, he was a nationalist.

Cabral and class analysis

That Cabral didn’t want to take on the ‘label’ of being a Marxist may have something to do with his analysis of the nature of Guinean society, and the basis for the national liberation struggle there. Guinea was an overwhelmingly rural and agricultural society. At university in Lisbon, Cabral and others had, of course, been exposed to Marxist and socialist ideas, so when deciding to start the struggle for independence, they had certain ideas about how to best pursue their aims: ‘We went looking for the working class in Guinea and did not find it’ (p.109). Of course, he means here not that there literally weren’t wage earners in Guinea, but rather that there wasn’t an organised, industrial proletariat. Where he does discuss workers such as dockers or boatmen, Cabral writes ‘You will notice that we are careful not to call these groups the proletariat or working class’ (p.102). Since later (p.106), he notes that these workers have an ‘extremely petit bourgeois mentality’, his point seems to be that Guinean workers did not have enough class consciousness to act as a revolutionary core.

Without a large working class to lead a revolutionary struggle, Cabral and his comrades had to consider what other social resources existed. He further insisted that ‘We do not consider that the peasantry in Guinea have a revolutionary capacity’: ‘Many people say that it is the peasants who carry the burden of exploitation; this may be true, but far as the struggle is concerned, it must be realized that it is not the degree of suffering and hardship involved as such that matters’ (p.106). It is urban people who could more readily see the differences between themselves, and the privileged layers of colonialists and their allies in the Guinean population; their immediate experience was the basis for the anti-colonial struggle. Eventually, peasants would form the largest numbers in the liberation party, and the armed struggle would grow in rural areas, but the impetus did not originally come from them. Cabral was thus originally thrown onto depending upon the ‘petite bourgeoisie’ for a revolutionary cadre.

Engles said of the sixteenth-century radical Thomas Müntzer that the

‘worst thing that can befall a leader of an extreme party is to be compelled to take over a government in an epoch when the movement is not yet ripe for the domination of the class which he represents and for the realisation of the measures which that domination would imply. … What he can do is in contrast to all his actions as hitherto practised, to all his principles and to the present interests of his party; what he ought to do cannot be achieved. In a word, he is compelled to represent not his party or his class, but the class for whom conditions are ripe for domination.’[i]

[i] Friederich Engels, ‘The Peasant War in Germany’ in The German Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1967), p.104.

There was no Guinean proletariat for Cabral to mobilise into revolution, so he had to rely on the class (from which he himself sprang), but which he clearly distrusted, the ‘petit bourgeoisie’.

The petit bourgeoisie and revolution

Cabral had no illusions about the difficulties that the petit bourgeoisie posed as the basis for a revolution. He divides them into three subgroups. One, ‘most of the higher authorities and some members of the liberal professions’, is compromised by its association with the colonial authorities. Another group that ‘we perhaps incorrectly call the revolutionary petite bourgeoisie’ is nationalist and the ‘source of the idea of the national liberation struggle in Guinea’. The third vacillates between the Portuguese and the liberation struggle. Below these sectors lay such groups as the dockers, who were more likely to be committed to the struggle, but were difficult to mobilise (pp.105-6). Elsewhere, Cabral warns of the danger of officials and intellectuals using the liberation struggle ‘to eliminate colonial oppression of their own class and to reestablish in this way their complete political and cultural domination of the people (p.87). The ‘normal tendency of the petit bourgeoisie is towards bourgeois behavior – to want to be the boss – and development of the struggle can crystallise in this way … there is always a strong tendency for the framework of the movement to acquire a bourgeois caste’ (p.30).

Cabral goes so far as to ask whether in fact ‘the national liberation movement is not an imperialist initiative’ since he judges the character of the struggle as tending to bring the petit bourgeoisie to power: ‘to hope that the petite bourgeoisie will just carry out a revolution when it comes to power in an underdeveloped country is to hope for a miracle, although it is true that it could do this’ (pp.114-15). National liberation considered as an imperialist project is to consider that ‘the objective of the imperialist countries was … to liberate the reactionary forces in our countries that were being stifled by colonialism, and to enable those forces to ally themselves with the international bourgeoisie’ (p.115). In much of Africa, this is what the end result was: the creation of new ruling classes in the new independent states that have been, largely, partners for international capital.

Cabral argued that the necessity was to make an alliance with ‘the national bourgeoisie, to try to deepen the absolutely necessary contradiction between the national bourgeoisie and the international bourgeoisie’ (p.116). To accomplish this alliance, and to try to mould the petit bourgeoisie into a force for progressive national liberation, Cabral appealed to culture as the solvent. The petit bourgeoisie, caught between their inferior position in the colonial hierarchy and their alienation from ‘the masses, often at the cost of family or ethnic ties and always at great personal cost’, are a marginalised, alienated group. The conflicts of their marginalisation play ‘out very much according to their material circumstances … but always at the individual level, never collectively’ (p.126). This makes an appeal to ‘return to the source’ of their native culture particularly powerful: ‘It comes as no surprise that the theories or “movements” such as Pan-Africanism or Negritude … were propounded outside Black Africa’ (p.126).

Culture and revolution

Cabral, then, was not someone who saw culture as an autonomous factor in itself; in the 1970 speech ‘National Liberation and Culture’, he insisted at length that ‘culture has as its material base the level of the productive forces and the mode of production’ (p.82). The material and historical foundation for resistance to exploitation had to be analysed and understood, so African culture was a necessary, if ambiguous weapon (see p.94) in the national-liberation struggle, rather than an alternative to a materialist position. Furthermore, ‘the “return to the source” is not and cannot in itself be an act of struggle against foreign domination (colonialist and racist), and it no longer necessarily means a return to traditions’ (p.126).

Indeed the ‘liberation movement must be capable of distinguishing within it [the cultural sphere] the essential from the secondary, the positive from the negative, the progressive from the reactionary, in order to characterize the master line that defines progressively a national culture’ (p.88). Cabral pointed out that there was not ‘one and only one culture’ in Africa, and named some of the ‘harmful’ aspects of an emphasis on culture: ‘blind acceptance of the value of the culture, without considering what presently or potentially regressive elements it contains … absurd linking of artistic creations, whether good or not, with supposed racial characteristics; and, finally, the non-scientific or a-scientific critical appreciation of cultural phenomena’ (p.92).

Culture is one the one hand ‘an inexhaustible source of courage, of material and moral support, of physical and psychic energy … But equally, in some respects, culture is very much a source of obstacles and difficulties, or erroneous conceptions about reality … and of limitations …’ (pp.94-5). Cabral in the end outlined a dialectical view of culture: ‘we see that the armed liberation struggle is not only a product of culture but also a determinant of culture’ (p.96). It was not culture that was the source of liberation, but the process of struggle itself which could remake culture, and open up new possibilities.

Cabral clearly deserves to be honoured and remembered not just as a hero of the age of the liberation struggles, but as a clear analyst of the nature of the struggle. He may not have wished to be troubled with labels, but his commitment to materialist, indeed class, analysis of the problems of the struggle are made very clear in the lucid texts gathered together here. Now that Africa’s working class is so much larger than it was in Cabral’s time, it can be hoped that a new liberation struggle based on that class could finally rid Africa of imperialist domination, and the exploitation of all exploiters, African and Western.

Comments are closed.