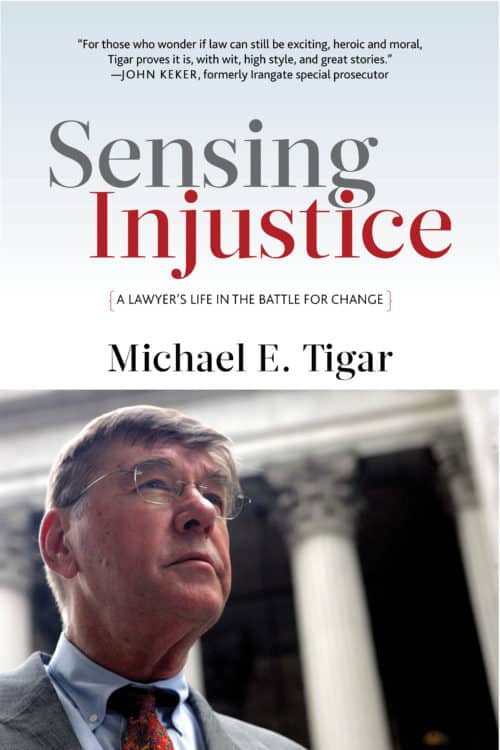

A talk given by law professor Jennifer Laurin in honor of the launch of Michael Tigar’s book, Sensing Injustice: A Lawyer’s Life in the Battle for Change

“How can I convey to you the experience of reading Michael’s book? Well, there are the basic attributes: Some 500 pages . . . 17 chapters, which begin chronologically with the early years of Michael’s life, and then shift to being organized thematically according to the immense range of legal issues on which Michael has labored over his career – challenging the surveillance state, representation of draft resisters, criminal defense work challenging instances of prosecutorial overreach, litigating government regulation and prosecution of speech, challenging the government’s use of the death penalty, and pressing the envelope of international human rights law in the U.S. and abroad.

I want to suggest – at the risk of prompting disagreement from the author – that this journey through the events and lessons of Michael’s life in the law reads as not one book, but at least three . . . and that one of the great pleasures of reading Sensing Injustice is the experience of moving among the different tones and modalities of these three different works compressed into a single volume.

One of the books that Sensing Injustice is, is personal memoir – a coming of age story, if you will. We learn of Michael’s family history in California and beyond, his childhood spent voraciously reading, bicycling around the Los Angeles suburbs, and developing his dramatic gifts.

We meet his family – in particular, the single, working women who raised him, and his union organizer father, Chuck, who Michael lost first to divorce and then to an early death – but not before Chuck advised 15-year-old Mike, presciently, to be “a lawyer like Clarence Darrow” – “for the people.”

We see Michael as a Berkeley undergrad and law student in the foment of the 1960s – literally finding his voice at the college radio station, and more figuratively in his journey in and out of the Navy reserves, his work challenging loyalty oaths and representing leaders in the Free Speech Movement, and the deep historical dives that he pursued in his earliest legal scholarship. We watch him grapple personally with the toxic combination of government overreach and official timidity – a combination he will battle for his entire career – when his clerkship with Justice William Brennan was withdrawn on account of official distortion and mendacity about those same Berkeley activities. We see Michael dust himself off from that and we meet Michael’s great mentor Ed Williams, founding partner of what would become the Williams and Connally firm in Washington D.C., and we watch Michael absorb the craft of advocacy at Williams’s knee, eventually to chafe at the constraints of firm life and launch his own prodigious practice in which he would be free – or as free as finances and family allow – to choose cases with meaning – cases that activated his SENSE of INJUSTICE. This book is a story of Michael seeking, finding, and honing his quite singular voice in the law.

But in Sensing Injustice I read a second book as well. I’ll call it the law school text Michael wishes he had been assigned in his years at Berkeley where he was, on his critical account, shown all branches and no roots. We learn a lot of law – but in a distinctive way. As we explore with Michael the various issues that have driven him in his career, meet the clients whose stories he has aimed to tell and the prosecutors and judges that he has in some mix challenged, managed, and educated – we see cases not as isolated moments of litigation, but as connected to a holistic understanding – Michael’s holistic understanding – of law’s history, structure, and progress. In journeying with Michael through his development of the Selective Service Law Reporter and his representation of draft resisters – David Gutknecht among them – we learn not just of the applicable law governing the cases but of the history of conscription, the evolution of an increasingly arbitrary and lawless administrative apparatus dictating the fate of young American men, and the racist consequences of its operation.

When we journey with Michael to Pittsburgh to represent steelworkers to challenge agreements entered into by their union leadership, we engage not only with the applicable provisions of the Landrum-Griffin Act, but with the history of American labor and workers’ rights and the interplay of litigation with labor movement organizing. I could go on.

In case after case – from United States v. Alderman to the Chicago 8, to the Pinochet case and all points in between, Michael conveys his distinctive gift for situating present legal disputes in broader legal historical context, and in so doing connects the events of the book not only to each other – through the continuity of his determination to challenge government impunity and the stifling of expression however it occurs – but also to a larger historical arc of the law’s role in delimiting state authority.

Finally, Sensing Injustice is yet a third book – a Self Help book of sorts, with an intended audience of law students and young lawyers aspiring to a life – and career – of consequence. At times Michael pauses narrative – breaks the fourth wall, in a sense – to distill and impart concrete lessons from his experiences. And then, some accumulated wisdom emerges more gradually and implicitly over the course of the book. Here are a few pieces of advice I got from Michael, that I would have liked to have had earlier in my career.

Make sure your case tells a story – a story of your client and a story of the law.

Be wary of judicial and prosecutorial ego – but know that there are people with both power and conscience.

Trust the capacity of jurors to learn and dispense justice.

Decide what you want and ask for it.

Don’t mistake lawyering for movement work – but don’t forget about the movement either.

Believe that one case at a time can, over time, make a difference.

Bring others along on your journey – and remember their contributions to it with graciousness and gratitude…..

Speaking personally, I myself had the great pleasure of spending a brief time alongside Michael – when I was one of the many “law students” of whom he speaks in the book, working with him in the trenches.

My chance came in defense of Lynne Stewart – the last trial of which Michael writes in the book, and one that, to an improbable degree, encapsulated in a single case all the themes of Michael’s career to that point. Lynne was a New York City criminal defense lawyer – a National Lawyers Guild member – known for representation of political dissidents. Among Lynne’s clients was Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the Blind Sheikh, convicted for his role in the first World Trade Center bombing. In 2002, in the heady post-9/11 days when the sound of helicopters made New Yorkers anxious and Muslim men were being disappeared on material witness warrants, Lynne was indicted for a range of crimes including conspiracy to provide material support to a terrorist organization – all premised on words she had spoken and services she had rendered in the course of providing representation to Abdel-Rahman.

As a progressive law student hoping to embark on a career litigating on behalf of causes that are inconvenient to the government, I took the prosecution not only as a tremendous assault on freedom of expression and the right to counsel itself – but as a personal threat to my chosen path in the law. It was a tremendous honor to be drafted by Michael to help beat that back, and I still have vivid memories of working away in my apartment on 105th Street until the wee hours of the morning, trying to master First Amendment law forged in many of the cases Michael discusses in the book – the Benjamin Spock case, the Dominic Gentile case, Brandenburg – and I retain ever-lasting gratitude for the graciousness Michael showed me in allowing me to run with substantial pieces of the motion to dismiss Lynne’s first indictment.

And we won that motion.

But a second indictment would follow, and Lynne was ultimately convicted – in a trial in which, as Michael tells it in the book, the court refused Lynne’s request to be severed from her significantly more deeply inculpated codefendants, allowed the Government – over defense objection – to regale the jury with video of Osama Bin Laden and evidence of terror attacks to which Lynne had no demonstrated connection, over the course of 9 months, in a courthouse blocks from the site of the September 11 terror attacks. Lynne received a 10 year sentence, and died of cancer in 2017 shortly after being granted compassionate release from federal prison.

My experience working on Lynne’s case was, I think, something like Michael’s in the early days of his work with Ed Williams: I emerged from the experience an infinitely more capable and confident lawyer, encouraged by Michael’s example of forging principled conviction with lawyering at the highest level of the craft. And, like Michael’s time with Ed, I got a couple of fancy dinners and nice glasses of wine out of the deal as well.

But I gather that Michael exited the experience significantly more battered. He gives much attention to presiding Judge Koeltl in his account – and I wonder, in a risky moment of armchair psychology, whether this is because Michael was disappointed that Judge Koeltl’s performance was another instance of official timidity in the face of government overreach – rather than something else, something more noble. But I think that in concluding his account of his courtroom work with this quite difficult experience of loss, Michael reminds us that battling against injustice doesn’t often look like what he absorbed in the movies and adventure books he avidly consumed in his youth.

It is not all swashbuckling and riding off into the sunset – however much Michael HAS swashbuckled and ridden into the sunset in his career. Rather – heroism in this work is manifest in the commitment to stand by the client, to tell their story, to do your damndest to find those crevices in the law that can be carved a bit wider to vindicate their struggle, and to journey with them wherever the reforged path of the law leads.

Thank you for the book, Michael, and thank you for your work.

Pick up a copy of Sensing Injustice and receive a free ebook, full with links to Michael Tigar’s legal arguments. Become a retroactive participant in the investigative research process that Tigar himself went through.

Comments are closed.