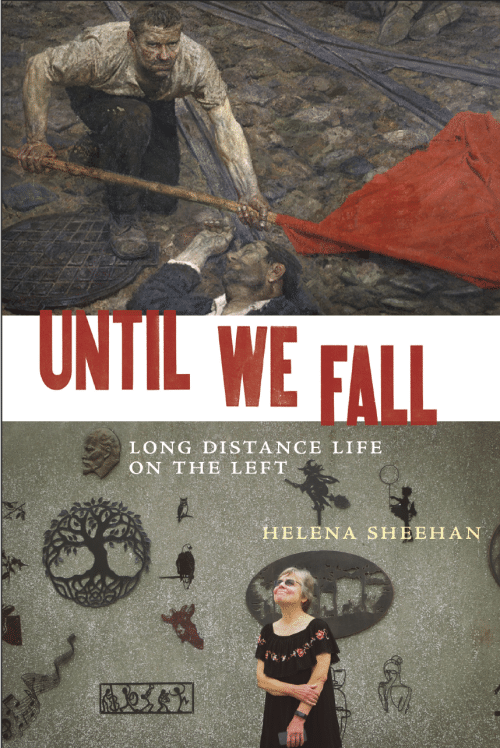

Until We Fall: Long Distance Life on the left

By Helena Sheehan

$28/360 pages/978-1-68590-027-4

Reviewed by John Green for Morning Star

FOLLOWING on from her riveting first autobiographical volume Navigating the Zeitgeist, which captured 1950s cold-war America, the 1960s new left, and 1970s social movements, Helena Sheehan now gives us a follow-up of her extraordinary life. Until We Fall begins in the late 1980s and offers vivid accounts of her encounters with fellow socialists around the world, while still attempting to navigate the zeitgeist.

From a conservative, Catholic Irish-US family background, Sheehan became deeply involved in the feminist, peace and civil rights struggles in the US, before settling in Ireland, where she continued her political development, becoming involved with Sinn Fein, socialist and communist parties.

Sheehan is an ideal partner to accompany in an exploration of the zeitgeist. She is a renowned Marxist philosopher and has written an insightful book on Marxism and the Philosophy of Science and more recently a perceptive analysis of the Syriza phenomenon in Greece, among others.

She begins this volume in the late 1980s, with the rise of Gorbachev and the helter-skelter process of socialist disintegration in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. She knows these countries intimately and also many of the leading figures in the academic and political world with whom she engages, as well as chatting to ordinary citizens.

She is a keen observer and listener and is a regular participant at conferences where socialist issues are debated. She reveals the polarisation between many of those attendees from the former communist countries and their counterparts in the West. The former often accuse Western leftists of being idealists and only knowing the theory, whereas they have experienced the practice of “real existing socialism” and know its deficiencies first-hand. Some of those from Eastern Europe view socialism as a system only needed by the poor and see “social market” capitalism as a better alternative for their own nations. Another example of being determining consciousness!

The break-up of the socialist countries and their replacement by atavistic nationalism, she sees as just another symptom of people’s loss of a unifying philosophy (and purposeful lives) as well as a sense of international solidarity.

Sheehan, though, looks beyond the problems facing each nation state and sees recent developments in a global context. With the global balance shattered, she is worried about what the demise of the socialist bloc means also for African and Latin American countries.

She notes that, already in the early 1980s if not before: “It was clear to most of us that socialism couldn’t survive without radical democratisation … it had to be based on consent.” Nevertheless, for Sheehan as for many of us on the left, the demise of the socialist bloc represented a defeat and the restoration of capitalism. It was “the most dramatic upheaval, politically and psychologically,” she says.

She travelled extensively in the socialist countries before and immediately after the demise of socialism and describes succinctly what was happening, but the rapidity of events and the apparent readiness of large sections of the population to abandon socialism did come as a shock. The preparedness of so many to “sell their souls to the devil,” seemingly unaware of what social values would have to be abandoned in order to enter “consumer heaven.”

She also travelled to the US — her former home — after several years away and finds a society also falling apart, albeit in a very different way. Society is fragmenting, there is widespread poverty and deprivation as well as a permanent fear, particularly among the middle classes, of losing stability in their lives. There is a lack of hope and of a firm belief in the system itself. On the left there is also fragmentation and lack of focus.

In Vienna in 1990, at a conference on the way forward in the wake of the collapse of “communism” in eastern Europe, she meets the Russian philosopher, Igor Tschubais of Democratic Platform who saw the national conflicts waging there as a reaction to a vacuum, to the loss of a unifying vision. This was also the opening decade of the “third way” encapsulated by Blair and Clinton.

As a university lecturer herself, Sheehan has an insightful chapter on the changes taking place in higher education as a result of the embracing of market forces, and another on developments in post-apartheid South Africa.

As a philosopher, she also scrutinises the various intellectual currents prevailing, particularly positivism and postmodernism, and makes a persuasive case for the explanatory and ethical superiority of Marxism.

As she moves through time and space, Sheehan pursues the perspectives of the vanquished in a world where the triumphalist narratives of the victors hold sway. The central thread of the book is her political activism as history swept through the left like a hurricane and challenged it in ever more formidable ways, bringing some victories but many defeats. She raises questions of how to keep going at a time when the old is dying and the new cannot be born.

This is a vivid personal and historical journey that really does capture the zeitgeist, and if at times the author runs the danger of making her narrative too I-centred, she is always able to pull back in time to return to the wider perspective. It is inquisitive, revealing and inspiring, offering hope if not solutions to the left’s dilemma.

Comments are closed.