Socialism & Democracy reviews Helena Sheehan’s “Navigating the Zeitgeist”

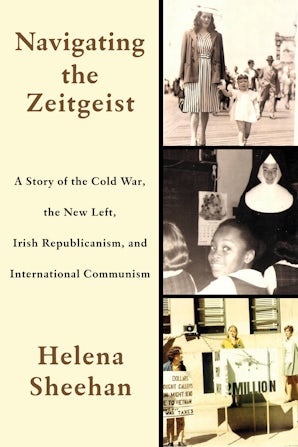

Navigating the Zeitgeist: A Story of the Cold War, the New Left, Irish Republicanism, and International Communism

308 pp, $25 pbk, ISBN 978-1-58367-727-8

By Helena Sheehan

Reviewed by Mat Callahan for Socialism and Democracy, vol. 33 (2019), no. 2, pp. 184-88

Navigating the Zeitgeist, is the first volume of Helena Sheehan’s two-part autobiography, covering the period between her birth in 1944 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Sheehan’s many books and essays include, Marxism and the Philosophy of Science, which made a vital contribution to both Marxism and remaining relevant, even urgent, to this day.

Navigating the Zeitgeist presents a fascinating account of events and personalities that Sheehan was deeply involved with. Each episode is given a critical and self-critical exposition, including evaluations of well-known political figures as well as some who were lesser known but equally important. Traversing Cold War America, Catholicism, the Sixties New Left, Sinn Fein and the IRA, the Communist Party of Ireland and the International Communist movement, Navigating the Zeitgeist is as much a sweeping overview as it is a personal narrative. In both senses, it’s an insightful and informative read.

Here I will concentrate on certain questions Sheehan raises along the way. When, for example, Sheehan grapples with “Marxism in power,” she’s referring to debates which erupted with some of her hosts while doing philosophical research in the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia and Poland. While she encountered many imaginative, critical thinkers in all these countries she was nonetheless confronted by the ossification of thought, the recitation of a catechism and the marginalization of serious inquiry for which socialism had long been condemned in the capitalist west. The struggles to remain loyal to the cause of international communism while maintaining one’s integrity are not only matters for the committed Marxist that Sheehan was and remains. They are serious questions for philosophy as a discipline, as indeed they are for anyone seeking to change the world.

Sheehan’s opening pages warn us that we are entering a battlefield. Mocking postmodernist tropes anointing the “decentered subject” or declaring the “grand narrative” passé, Sheehan uses both her life experience and her philosophical training to dismantle an edifice erected to lend an aura of irreverence to old-fashioned anti-communism. The challenge is not only to expose the fraud but to examine the deeper questions thereby obscured. To interrogate the failures of revolutionaries, in and out of power, while maintaining a commitment to revolutionary change is a task too few intellectuals have been willing or able to undertake.

Compounding the problem is an unwillingness or inability on the part of revolutionaries to squarely confront their failures, as if doing so were tantamount to betraying the cause. Each successive chapter of this book is a building block in an argument, a retelling not only of a sequence of actions but of the reasons people, including Sheehan herself, took them. An example of this is the process by which Sheehan left first her religious order and subsequently an entire way of life. Not only was Catholicism a totality or comprehensive worldview from which Sheehan was definitively and traumatically separating herself, but she was at the same time resolutely upholding the necessity for totality or a world outlook, albeit with diametrically opposed content to that of the Catholic Church. Knowing full well that such “totalizing discourse” is unfashionable, Sheehan nonetheless proceeds to explain her thought processes, concluding:

I know all the arguments against this made by positivists, neo-positivists, existentialists, postmodernists, all the sneers about changing one religion for another, but I stand by it. It is not as if I took another totality off the shelf. I knew what I was leaving behind, but I did not yet know what I would find ahead. (74)

This method is employed throughout, even as the terrain and terminology change.

Sheehan’s “witness” is one of active engagement in world-historic processes, an engagement without which there can be no consciousness of either the mechanisms or the stakes involved. Passive onlookers may hold opinions of processes over which they exert no influence. Only those who’ve committed themselves gain access to the truths emerging from the struggle against falsehood. Given that philosophy, from Parmenides onward, has differentiated “the way of opinion” from “the way of truth,” this is not a matter of rhetorical posturing but of definition and procedure; of logical consistency and empirical evidence; of fearless critique and taking sides. It is furthermore at the core of the very disputes Sheehan would later be embroiled in, which in turn reveal a great deal about what led to the “collapse of communism.”

It’s worth recalling that many people alive today were participants in the revolutionary upheavals of the period from 1960 to 1980. The Cuban revolution, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and the victory of the Vietnamese were high points of struggle convincing tens of millions that a new world was being born. This was not confined to what was then called the Third World. In the First and Second Worlds, insurgencies were mounted that made “revolution in our lifetime” a reasonable supposition. Indeed, Prague Spring and the “Troubles” in Ireland, exemplify the zeitgeist, as much as their counterparts elsewhere. Not only were millions directly involved, but they shared to one degree or another the commitments illuminating Sheehan’s account. What stands out in her book, however, is not what it has in common with the many memoirs, autobiographies and histories written of the same period, but what has been lacking in nearly all of them, namely: philosophy, especially, the philosophy of science.

Sheehan’s experience is evidence of how the destitution of philosophy was played out, how decay within the Soviet Union was in a sense foretold by the official treatment of philosophy as a dead letter. When Sheehan describes a chance encounter with Brezhnev, he appeared to her as a corpse, an apparition of a sealed fate.

Such dreary outcomes, Sheehan steadfastly maintains, are irreconcilable with the materialism of Marx and Engels. The philosophical and scientific premises on which their analyses and prognoses were made bear scant resemblance either to the tautologies propounded by various socialist regimes or successive intellectual fads pursued by ostensibly left-wing theorists in the west. Decades later, it remains crucial to grasp how anti-communism necessarily included an obscurantism towards science, a mystification of processes by which knowledge is attained and the quasi-religious elevation of difference over similarity, what divides as opposed to what unites humanity.

The great value of Sheehan’s account, therefore, is its relentless effort to ferret out core principles that must be fought for at all costs, especially in opposition to those falsehoods that, like shadows, attach themselves to those very principles. A prime example is the questions Sheehan raises surrounding feminism, more specifically, the conflict between socialist feminism and radical feminism.

Sheehan’s politicization began during the Sixties in the New Left. She became a feminist before she became a Marxist. Eventually, the study of philosophy combined with increasing political activity led her to study Engels, the author of The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. In a speech delivered at a Philosophical Society conference in Dublin, where Engels himself had once spoken, Sheehan recalls:

Following in the footsteps of Engels in more ways than one, I argued that the oppression of women was rooted in the social division of labor inherent in class society. It was grounded in private ownership of the means of social production. It was thus necessary for women to emerge from private work in the home and to enter fully into the sphere of social production. Marxism, I contended, was the only approach that conceived gender within a comprehensive world view, grounded in an analysis of socio-historic processes and the realities of political economy and that opened the way for the full liberation of women. Radical feminists argued that Marxism was a male theory and that could not

explain the oppression of women. (197)

This was in 1979. Forty years later, Sheehan’s defense of Marxism not only remains consistent; it facilitates critical engagement with radical feminism’s theoretical development over the same timeframe.

Standpoint epistemology and other “gendered ways of knowing” can be evaluated not only in abstract terms but in relation to the concrete conditions facing women and children today. No doubt, radical feminism’s critique of male supremacist ideology has produced tangible improvements in both societal attitudes and the legal status of women and girls. Nevertheless, the super-exploitation and oppression of women persists as a fundamental component of capital accumulation, with war and climate catastrophe its inevitable outcomes, all of which demand analysis found wanting in theories inspired by radical feminism, especially those which dismiss Marxism tout court as a “male” construct.

In a 1998 essay in Socialism and Democracy, “Grand Narratives Then and Now: Can We Still Conceptualise History?” Sheehan wrote:

What has set Marxism apart from all other modes of thought is that it is a comprehensive world view grounded in empirical knowledge and socio-historical process. All economic policies, political institutions, legal codes, moral norms, sexual roles, aesthetic tastes, thought patterns and even what passes as common sense, are products of a particular pattern of socio-historical development rooted in the transformation of the mode of production. It is not a predetermined pattern or a closed process. Although there is a determinate pattern of interconnections, the precise shape of socio-historical development is only discernible post factum, for history is an open process, in which there is real adventure, real risk and real surprise, a process in which there are no inevitable victories. (vol. 12 no. 1/2)

Space does not allow for a fuller discussion of all the ground covered in Navigating the Zeitgeist. As much as is written above could be said about Sheehan’s involvement with Ireland and its politics. Those unfamiliar with names such as James Connolly, Sinn Fein-IRA, “Provos” and “Officials,” Cathal Goulding and Seamus Costello, might find this section of the book daunting, although it certainly makes engrossing reading. For those who’ve been involved, however, Sheehan’s are not “cautionary tales” bemoaning sectarian violence and pointless internecine rivalry. What emerges are above all else political and philosophical issues having to do with revolution as a process, national liberation in an international context and, again, a sharp distinction between the passive observer and the active participant. Navigating the Zeitgeist demands that the reader acknowledge this distinction, not only to better understand Sheehan, but also so that we may be inspired to participate and not just observe.

–© 2019 Mat Callahan

Bern, Switzerland