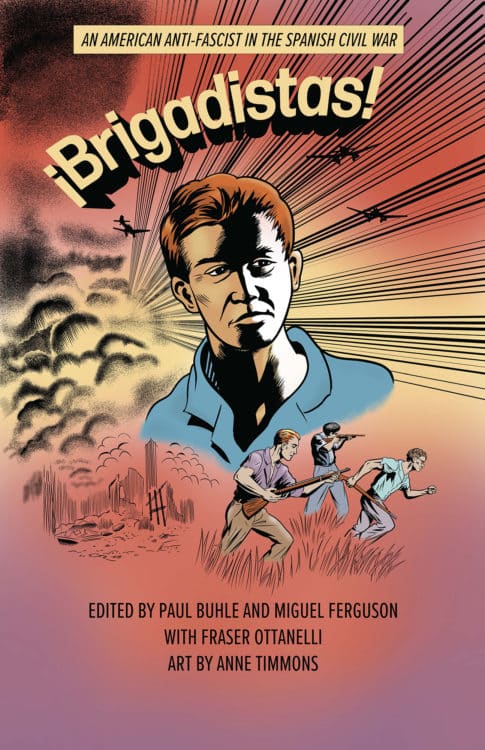

!Brigadistas!

An American Anti-Fascist in the Spanish Civil War

$18 paper / 978-1-58367-960-9 / 120 pages

Written by Miguel Ferguson, and edited by Anne Timmons

Edited by Paul Buhle and Fraser Ottanelli

Reviewed by Eve Ottenberg

The Spanish civil war of 1936 becomes more relevant every day. That’s because it was a war against fascism in its pure form. In case you wonder what form that is, amid the poisonous, weedy varieties sprouting up globally these days, it’s fascism, exercised through corporate control of government, against and thus persecution of leftists, non-Christians and trade unionists. If that sounds familiar, don’t be surprised to hear it spelled out: this is the explicit program of much of the U.S. Republican party. The Dems enabled it, make no mistake, and they are just as complicit in the corporate merger with government. But they at least have the good grace not to embrace the rest of it.

In Spain, when the fascists revolted, they did not make a mess of it the way our hapless January 6 rioters did. But don’t count on what happened once happening again. If ever a Bernie Sanders or any true social democrat should find him- or herself ascending to the white house, the oligarchs’ shock troops, those AR-15-toting, rightwing militias will attempt to head such a president off before arrival and block his or her passage, and will do so in the name of some cultural grievance, like that social democrat’s feminism or support of gay marriage, along with ignorant howls about that candidate’s Marxist-Leninist communism. Although the American elite was horrified by what Trump did January 6, don’t expect that horror to hold if the electors congress must certify support a candidate with openly socialistic leanings. A president who aims to institute government-paid-for medicine, housing, and higher education? You can be sure our corporate aristocracy will tolerate no such thing.

Sadly, social democrats are not great fighters. While the American right-wing does not want to admit it, (nor do centrist Dems or even, in fact, much of the left) the most effective fighters against fascism are communists and always have been. That’s because the communist analysis of fascism, as handed down by Leon Trotsky and Clara Zetkin is the most honest, lucid and unequivocating one around and it leads inexorably to the conclusion that only mass action, maybe even – as happened when confronting Nazism – antifascist violence, is the way to stop this horror.

In this regard, it pays to study the Spanish civil war. Right on time comes the publication of !Brigadistas!, a graphic novelization of the war by Miguel Ferguson. Now graphic novels and histories have a long, admirable left-wing pedigree, and this new account descends directly from them. “Comic books first seized public attention in the late 1930s moment of global dread,” writes Paul Buhle in the afterword, noting the popularity of war comics during World War II, especially Boy Commandos. “Multicultural, nonracist by implication, Boy Commandos was written by one of the coming giants of superhero comic books, Joe Simon, himself the son of a union organizer.” Simon didn’t hesitate to depict partisans taking revenge against fascists, in comics that modern day right-wingers would no doubt denounce as “antifa.”

But then, after Boy Commandos, came furious red-baiting censorship. Buhle writes that its effects stifled this art form and lasted until the Vietnam war protests. That’s when graphic comic artist Spain Rodriguez appeared. He was “sui generis among the peaceniks of the Bay Area circles of artists.” His comic art portrayed “tough left-wingers fighting a cruel and destructive social system.” Rodriguez’s “graphic story of Che [Guevara] is the precursor to !Brigadistas!”

This new book recounts the struggles of young communists from Brooklyn who travel to Spain to fight fascists. Several real-life left-wing heroes make an appearance, for instance African American labor organizer and anti-fascist Oliver Law, along with radical left-wing novelist Ernest Hemingway and journalist Martha Gellhorn. The book fictionalizes the heroism of anti-fascist Abram Osherhoff and his comrades, starting with the young communists tearing down and attempting to destroy the swastika flag on the German ship Bremen, docked in New York harbor.

A Spanish republican convinces Abram to join the anti-fascist fight with the words: “Senor Abe, the people who butchered the Jews during the Inquisition, they are the same kind of people who did this [Guernica]. This is who we fight.” The Popular Front helped arrange the leftists’ passage to Barcelona. But despite the many who joined these international brigades, determined to “make Spain the tomb of fascism,” the odds were against them. “No guns, no food, no water,” one American complains in this new book. “This is a helluva way to run a war.”

Fascists are always better armed. Just look at our own, homegrown militias, with the most up-to-date semi-automatic weaponry, while antifa faces them with what? Baseball bats? What Abram writes to his girlfriend holds true of the antifa left today: “Hardly anyone here has military experience. Most of us are union members and working stiffs, but there are artists and writers and all sorts from all over the globe.” Unfortunately, most of the soldiers during the Spanish civil war were to be found on the fascist side. And the only place large numbers of anti-fascist soldiers might have come from, namely, the USSR, didn’t provide them. To its credit, however, the Soviet Union supported the Spanish antifascists in many other ways, when the rest of the west left them to twist in the wind.

The type of graphic history and art exemplified by this tradition of comics went against what Buhle calls “the politically indifferent ‘free enterprise art’ mood of the cold war 1950s.” In painting, that was shortly after the start of abstract expressionism, so eagerly promoted and funded by the CIA. After all, it’s hard to depict social reality when your style is abstract, and social reality was what the CIA sought to quash. Social realism was mocked in the west, despite that fact that most of the greatest novelists who ever lived practiced it. No, the CIA message was: “We in the west have fun with abstract art, while communists portray the gloomy, boring suffering of ordinary people.” So did Balzac, Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Zola, countless other literary titans and painters like Goya and David, but so what? The CIA had a psychological war to win. It succeeded with painting and sculpture, and the trend influenced modernist and post-modernist literature and music. But some artists nevertheless remained committed to reality and its humongous historical artistic heritage.

The cost of this ideological campaign against the true subject of literature and art, to wit, depiction of social reality, was enormous. Though Balzac, for instance, personally espoused royalist politics, his more than one hundred novels present a different vision, one that radicalizes into serious leftism any reader not deficient in either the brain or the heart; but that particular radical insight into the world’s true workings cannot occur if Balzac is not read, and in the U.S., outside of university romance language departments, he is not read.

Which is catastrophic, because Balzac was prescient to the point of infallible soothsaying. Take, for instance, his colossal masterpiece, his novel Lost Illusions, about journalism, poetry and other literary arts. It stands as valid today as it did in the nineteenth century, as an indictment of the commodification of literature. It lays bare once and for all, how that commodification occurred and at what human cost to the writers it affected. This novel analyzes, far more profoundly and trenchantly than Gissing’s New Grub Street, a process that altered literary ecology forever – indeed what novelist or journalist today can even conceive of living in a world where the rules of the literary marketplace do not hold? To find such a pristine environment you would have to travel back to medieval times and who wants to, or can arrange their writing thus? Balzac would not have been surprised at how the CIA attempted to pervert and hijack literature; his only shock would have been at how long it took for this to happen, namely not until the mid-twentieth century.

As the stupendous Marxist literary critic Georg Lukacs would have told you in a heartbeat, any literary subject other than the true machinery of social reality is puny and puerile, thus the trivialization of so much contemporary art and literature, with notable exceptions like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s oeuvre. Because lamentably, after the mid-twentieth century, western art was hobbled and so, deliberately, was its ability to aid social and political movements. But one corner of the artistic world, graphic comics, proved surprisingly resilient. This genre survived political censorship, bounced back in the 1960s and started, once again, doing what all great art does: revealing deep truths about human reality.

See Counterpunch for the full review.

Read the full review at Portside NY

Comments are closed.