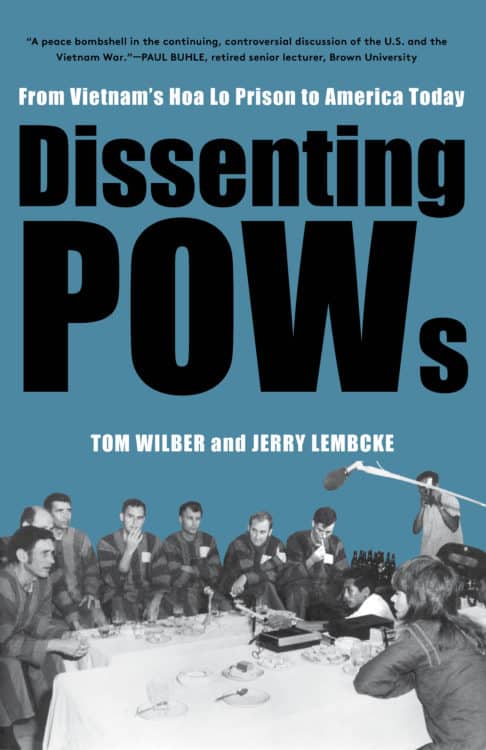

Dissenting POWs:

From Vietnam`s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today

by Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke

160 pages, $19 paper, 978-1-58367-908-1

Reviewed by Peter Arkell for Real Democracy Movement

Between a third and half of the nearly 600 American prisoners-of-war (POWs) released at the end of the war in Vietnam in 1973 were opponents of the war, on moral, political or conscience grounds.

This fact presented the Nixon administration with a big problem – how to bury this uncomfortable fact when the POWs returned to the US.

To achieve this, the US government relied heavily on the senior returning officers (SROs), the higher-ranked men who had been captured and held with the conscripted or enlisted men, in Hanoi.

Unlike the ordinary soldiers these were professionals whose careers depended on their success, so most of them carried on fighting the war – as prisoners-at-war.

In their new book, Dissenting POWs, Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke give a vivid picture of the conflicting ideas and opinions – a class war really – that took hold within the prisons.

The prisoners were not a homogenous group, being split three ways. There were the pilots, usually well-educated but with little knowledge of Vietnam or its people, having baled out of their bombers after being shot down, and then captured.

Conscript soldiers were working-class GIs and marines, with less formal education than the pilots. Most of them were captured by the Viet Cong. These men had had direct contact with the Vietnamese, living as they had for up to a year in South Vietnam.

They would have seen and talked to civilian employees on the bases, street vendors, bar girls and some may even have had Vietnamese girl friends. And then there were the SROs, many of whom felt they had to continue the war as prisoners.

“The social distance between the SROs and the enlisted men was a good indicator of who would be a dissident,” the authors write. “By the time of the POWs release and repatriation in early 1973, the war between the walls of Hoa Lo (the prison near Hanoi) was more than that between prisoners and their guards. The tensions between the officers and the enlisted men, universal in military organisations, had hardened into class lines.”

The men openly dismissed the authority of the officers, while the officers wanted to develop their prisoner-at-war narrative and their tough-guy never-say-die personas. So they provoked the guards, welcomed punishments, sometime even beating themselves up deliberately to pretend they had been tortured. Essentially, they tried to establish a regime of belligerent non-co-operation by example, expecting the men to follow.

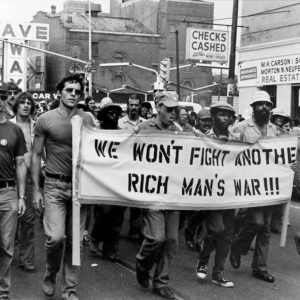

But the ranks had other ideas. They knew of the anti-war protests at home and of the visits to the prisoners by the Peace Committee, Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden and other celebrities campaigning to end the war. And many of them sympathised with the general aim of the Vietnamese to be free of wars and colonial powers.

It was, of course, the officers’ stories that tended to fill the newspapers when the prisoners were repatriated – at first. Their stories chimed with the consciousness of the people in the US who had derived a lot of their understanding from films such as The Manchurian Candidate with its theme of brain-washing.

The figure of the hero-prisoner was a well-established myth in popular American culture, and these culture myths, in conjunction with the cold-war obsessions about communist mind-control, and religious influences, banished the story of the dissenting POWs to the margins.

“The history that POWs conscientiously opposed the war before and after their return from Hanoi, was not so much erased or suppressed from public memory as it was displaced or over-written by other related story-lines,” the authors write.

Wilber and Lembcke effectively trace the line of power from the top, from the war-like stance of the American state, through its spokespersons, through the army SROs and the mainstream media, and into the population as a whole.

The facts of the resistance of the dissenting prisoners-of-war got pushed aside, and replaced in the end with a whole lot of myths about the mental reliability and well-being of the prisoners.

But it is not a wholly depressing narrative, the book argues:

Fifty years after the war in Vietnam, the acts of conscience displayed there, and the reaction they provoked continue to drive American political culture.

Comments are closed.