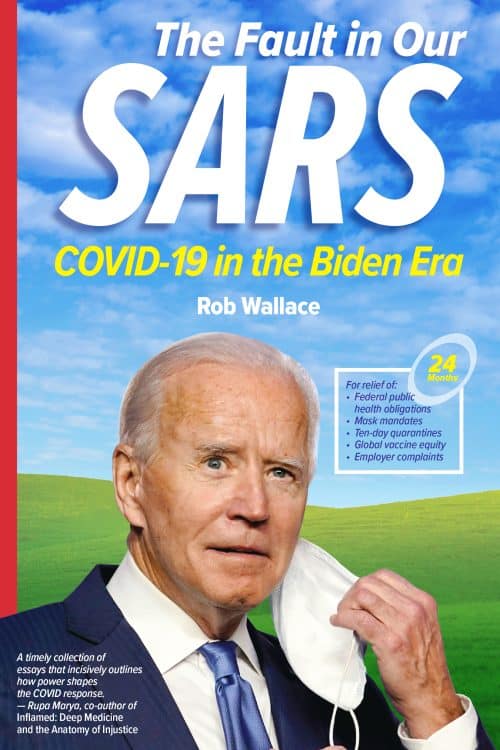

The Fault in Our SARS: COVID-19 in the Biden Era

512 pages / 978-1-58367-9937 / $26

By Rob Wallace

Reviewed by Sean Ledwith for Counterfire

American voters are facing the decidedly unappetising prospect later this year of a re-run of the 2020 presidential election between Biden and Trump. Many of those voters will find it baffling that a nation of over 300 million cannot find a more appealing choice of candidates, or that they realistically only have a choice of two discredited parties. If 2020 is anything to go by, whatever the outcome this year, the US political system is confronting an existential crisis. If Trump wins, it is almost unimaginable what his deranged ego might do with a second dose of presidential power. Recently he has stated he will ‘rule like a dictator from day one’ and ‘revenge’ will be on the immediate agenda. If Biden wins, Trump’s activist base on the far right will probably mobilise for a repeat of the infamous Capitol insurrection in January 2021 that witnessed barely believable scenes of Congress been overrun by a quasi-fascist mob. Faith in the country’s much-vaunted constitution could be stretched to breaking point.

Trump might have lost last time round, but his insidiously effective peddling of an American version of the Nazi ‘stab in the back’ myth from the post-World-War-I era has enabled him to dominate US politics as a backseat driver since 2020. Trump’s steamrolling of potential Republican rivals in the primaries this year demonstrates his vice-like grip of the party of choice for the US capitalist class. His graceless departure from office last time was met with a collective sigh of relief from the rest of the world. The notion of his bellicose and infantile personality returning to the Oval Office in a world wracked by crises in Ukraine and Gaza, alongside the accelerating effects of climate change, is enough to drive anyone to despair.

The greatest calamity of that first Trump term in the White House, of course, was his grotesque mishandling of the Covid pandemic. From his initial dim-witted refusal to take the threat seriously in early 2020, to his infamous advice to drink bleach as a treatment, the Orange abomination managed to turn a disaster into a catastrophe. The federal Center for Disease Control (CDC) has now ceased collating Covid-related fatalities in the US but the figure from last summer stood a 1.1 million, with an additional twenty million suffering from the effects of Long Covid.

Private wealth vs public health

Rob Wallace established himself as the most authoritative voice on pandemics on the US left in the years leading up to and including that first wave of the crisis in 2020 with books such as Big Farms Make Big Flu and Dead Epidemiologists. In those works, Wallace adopted an explicitly Marxist perspective on the pandemic which powerfully synthesised incisive critiques of the bungled policy response of the Trump administration with a contextual analysis of the wider capitalist system’s prioritising of private wealth above public health. Wallace, a professional evolutionary biologist, writes in Dead Epidemiologists:

‘The cause of COVID-19 and other such pathogens is not found just in the object of any one infectious agent or its clinical course, but also in the field of ecosystemic relations that capital and other structural causes have pinned back to their own advantage … the hidden-in-plain-sight truth behind the pandemic: global capital drove the deforestation and development that exposed us to new pathogens.’

Aside from his valuable publications and running commentary on the pandemic, Wallace is a key member of the People’s CDC, a grassroots pressure group which seeks to keep Covid in the spotlight at a time when capitalist politicians would prefer us to forget about it.

The Fault in Our SARS represents a sequel to those earlier works and a continuation of the story of the pandemic in the US that brings it up to speed with an analysis of Biden’s handling of the situation since 2021. Many Americans would have been relieved to see the current President entering the White House that year, assuming he would mark a clean break from the madness of the Trump years. Wallace in this volume, however, is equally scathing of Biden’s management of the crisis as his earlier works were of Trump.

Wallace’s Marxist lens enables him to see through the false alternative historically offered by the Democrats to the corporate agenda of the Republicans; on the specific issue of Covid, to see through the hollow promises of Biden to deliver America from the shadow of the virus. The fact that the previously unthinkable prospect of a second Trump term is becoming real, Wallace argues, is due in no small part to the failure of Biden to construct a credible alternative since 2021. He writes:

‘The political class here simply can’t afford the possibility that US governance in late empire, focused on corporations and the stock market first, suddenly would be centred on hiring the American people to help the American people. FDR bunting is being placed on an austerity parade float’ (p.33).

Ruling-class continuities

Wallace notes the fundamental fallacy at the heart of the argument that the Democrats represent an authentic alternative to the Republicans. Each period of Democrat control of the White House in recent history leads to an inevitable disillusionment that allows the Republicans to return to power. Democrat Presidents like Clinton and Obama take office with high-flown rhetoric about the American dream, but then step down after two terms of failure and make way for a right-wing successor in the form of Bush or Trump. The possibility that Biden may become a one-term President later this year underlines the dead end of conventional politics in the US:

‘Could the so-called moderates of the extreme center that turned a sure thing of an election into a nailbiter possibly miss the perils of resetting the political pins for a fascist of even a modicum of competence greater than Trump?’ (p.30).

Wallace observes that a year after taking office, Trump’s successor in the Oval Office had effectively given up on the possibility of eradicating the virus: ‘By April 2022, the Biden administration had helped strip the US capacity to keep track of Covid-19. The Department of Health and Human Services ended the requirement hospitals report daily Covid deaths, overflow and ventilated Covid patients and critical shortages’ (p.17). When Biden himself caught the virus in July of that year, it was noted that he attended work multiple times without a mask. By August, the CDC had abandoned recommendations for quarantining at home and testing people without symptoms.

Wallace neatly sums up the sense of relief many Americans felt that Trump lost in 2020 without any sense of enthusiasm for his successor in the phrase, ‘Bidenfreude’. He uses Freudian imagery to emphasise the continuity of policy between Trump and Biden regarding the pandemic: ‘Biden and his Covid-19 response embodied as much of the epoch’s exhausted spirit as Trump. Whereas Trump represents the system’s id, Biden campaigned as its science-touting superego only now, once elected, he’s back to acting its trap of a structurally imposed ego’ (p.51).

Polycrisis and hope

Another impressive feature of Wallace’s approach to the pandemic is a broad focus that perceives that disaster as part of a wider crisis of the system that is playing out on multiple levels. In the US, the first year of the pandemic was notable not just for the impact of the virus but also for the explosion of Black Lives Matter activism in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Wallace notes the disproportionate impact on African Americans of both the virus and police brutality are evidence of a structurally racist social order. In the county where Floyd lost his life, it is a remarkable and horrifying fact that unarmed black people are twice as likely to be shot by the police as armed whites! (p.124). In Wallace’s words:

‘All such murders back hideous political economies of racial terror and expropriation that, along with the pain and punishment they embody on their own, also drive so much of Earth’s ecological damage, pandemic included’ (p.124).

The book was completed before the current crisis in Gaza which commenced with the Hamas attack on southern Israel on 7 October last year. However, the author is alert to how the long-running Israel-Palestine conflict is another symptom of the accelerating degeneration of global capitalism we are now witnessing. The callousness of the world’s ruling classes, which has led to an estimated six-million people dying of Covid, is also apparent in the daily attacks on Gaza being conducted by the Israeli state: As Wallace writes:

‘the strafing lines of bombs through a densely populated Gaza City are also reminiscent of footage of US napalm dropped through Vietnamese jungle. Stochastic terror and collective punishment as a form of punishment … from dust, loss of work, and destruction of roadways, gas lines and water lines. All summing up to a message that any resistance to apartheid is to be paid for in dead kids’ (p.103).

There is always the possibility that books such as this which forensically dissect the cold-blooded ineptitude of capitalist politicians leave the reader in a state of despondency regarding the prospects for humanity. Wallace however is refreshingly optimistic about the future and perceives that in recent American politics there are sparks of hope that may come together at some point. The BLM campaign, Bernie Sanders’ presidential runs, Amazon trade unionists and pro-choice campaigners across the country are all indicators that a revival of the US left could be imminent. Wallace observes:

‘We feel trapped in the tangle of techno-linguistic automatisms: finance, global competition, military escalation. But the body of the general intellect is richer than the connective brain. And the present reality is richer than the format imposed on it, as the manifold possibilities inscribed in the present have not been wholly cancelled, even if they seem presently inert’ (p.156).

Comments are closed.