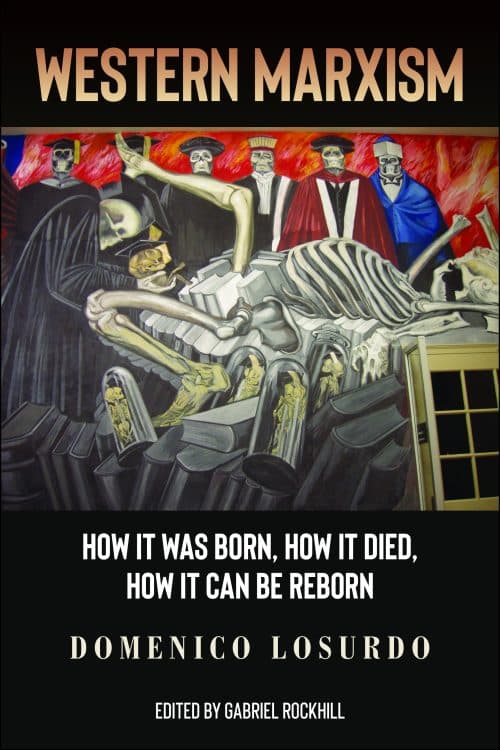

Western Marxism

By Domenico Losurdo

352 pages / $32 / 978-1-68590-062-5

Reviewed by Prince Capone for Weaponized Information

This is not just a book review. It’s a dispatch from the ideological frontlines of a world teetering on the edge of annihilation, where nuclear weapons, climate collapse, and AI-powered technofascism are all governed by the same iron law of profit. Into this chaos comes Domenico Losurdo, philosopher and partisan, armed with a scalpel sharper than any critique produced in the gated seminar rooms of Western academia. His book, Western Marxism: How It Was Born, How It Died, How It Can Be Reborn, is not just an autopsy of a failed theoretical tradition. It’s a funeral for the kind of Marxism that refuses to fight—and a call to arms for the rest of us who are tired of watching theory become therapy for cowards in tenured chairs.

We live in a moment where the most celebrated “left” thinkers are endorsed by NATO-funded journals, offered slots on the Foreign Policy Top 100 list, and deliver TED Talks for Google. What passes as Marxism in the imperial core has become, to borrow Losurdo’s phrase, a politics of defeat: obsessed with failure, allergic to power, and deeply invested in moralistic sneering at those who dare to build. This book enters like a molotov through the stained-glass windows of Verso Books and the New Left Review, shattering the illusions that critical theory, in its Western iteration, ever meant to liberate anyone.

Losurdo’s method is not subtle—but neither is the betrayal he confronts. He traces a precise historical and class rupture: 1914 and 1917. The former marks the collapse of the Second International, when Europe’s socialist parties lined up behind their own bourgeoisies to wage imperialist war. The latter, of course, is the Bolshevik Revolution, where the working class, peasantry, and oppressed nationalities actually seized power and attempted to remake the world. From that moment forward, Marxism bifurcated. In the East: revolutionary practice. In the West: revolutionary rhetoric. One took up arms and expropriated the ruling class. The other picked up pens and began a century-long career in symbolic subversion and ideological retreat.

But Losurdo doesn’t stop at the betrayal—he names the class that benefited from it. Western Marxism, he shows, is not merely a school of thought; it is a political expression of the imperial petty bourgeoisie: academics, intellectuals, and cultural producers situated safely in the heart of empire, clinging to their university salaries, their speaking tours, and their fragile liberal reputations. These are not people committed to revolution. They are people committed to performing its language, while collaborating in its defeat. They publish on the suffering of the world without lifting a finger to end it. They mourn the dead of Vietnam, Cuba, and Burkina Faso while ridiculing the revolutions that tried to liberate them.

This is why Losurdo’s book resonates not as theory, but as diagnosis. Like Lenin writing from the trenches of Red Petrograd, he is not interested in abstract purity or fashionable jargon. He is interested in what works. He names the disfigured remains of Marxism in the West for what it is: an ideology of retreat that confuses cowardice for caution and impotence for insight. He calls out the priests of this new church—Adorno, Althusser, Sartre, Hardt and Negri, even Žižek—not to dismiss their contributions wholesale, but to rip away the aura of radicalism from their politics of permanent evasion. They are not dangerous revolutionaries. They are licensed radicals. Court jesters with citations.

This review, then, is not just an assessment of Losurdo’s book. It is a weaponization of his method. At a time when Western Marxism functions like a hospice for disappointed liberals and ex-communists, Losurdo’s analysis restores the revolutionary heartbeat of Marxism by reminding us that the struggle never stopped—it just moved East and South. It was in the rice paddies of Vietnam, in the sugar fields of Cuba, in the barefoot militias of Angola, in the People’s Communes of China. And it is there, in the concrete resistance of actual people against actual empires, that Marxism was reborn—not as theory but as fire.

If the Western Marxists want to mourn, let them. We have no time for elegies. Our task is resurrection—not of an abstract “Left,” but of Marxism as a living weapon in the hands of the global poor. And to do that, we must begin where Losurdo begins: by burying the corpse of critique and building something that fights.

The Class Politics of Critique: When Theory Serves the Master

If the first casualty of imperial war is truth, then the second is theory—because nothing reveals a thinker’s allegiance more quickly than the question of state power. Losurdo understands this. He knows that the central fault line separating revolutionary Marxism from its Western caricature is not the interpretation of Marx’s early writings, nor the fine print of dialectical method, but a single, burning question: do you stand with those who take power to end oppression, or with those who critique them from the safety of empire? In this, Western Marxism has betrayed not only the revolution, but the very class it claims to speak for. It has become the philosophy of those who flee the field of battle and mock the wounded on their way out.

Losurdo doesn’t just theorize this betrayal. He names it. He tracks it through the hallowed halls of Frankfurt, through the self-important salons of Paris, through the postmodern drift into abstraction. He shows how thinkers like Adorno and Horkheimer, intoxicated by their own refinement, openly sneered at the anticolonial revolutions of the 20th century. How Althusser’s “anti-humanism” became a euphemism for disengagement. How Sartre’s so-called anti-imperialism was often a populist theater of guilt without revolutionary commitment. And how the entire tradition increasingly reeked of moral superiority and Eurocentric despair.

But Losurdo digs deeper—he refuses to stop at ideological critique. Instead, he interrogates the material conditions that produced this shift. Western Marxism, he argues, is the ideological excretion of the imperial core’s class contradictions. It is a product of the global wage differential that enabled the rise of a labor aristocracy in the West, and of the professional-managerial intelligentsia that floated atop it. These are not merely cultural workers with opinions. They are salaried functionaries of the knowledge economy, whose radicalism rarely leaves the page. They do not want to overthrow capitalism—they want tenure within it. Their Marxism is not a weapon, but a credential.

This is why, as Losurdo shows, the CIA had no problem funding them. Through cultural fronts like the Congress for Cultural Freedom, imperialism propped up a “respectable Left” that would attack socialism in the name of critique while advancing the ideological aims of the empire. The real enemies—Leninists, Maoists, anti-imperialist revolutionaries—were demonized as Stalinists, totalitarians, or worse. But Adorno? Arendt? Marcuse? They were safe. Because their Marxism had already been defanged—stripped of its class allegiance, its organizational form, its revolutionary horizon. What remained was critique without consequence, rebellion without power, theory without teeth.

The result, Losurdo argues, is a Marxism that confuses its own impotence for ethical superiority. A Marxism that dismisses the victories of the oppressed—from Vietnam to China to Angola—as failures because they do not conform to the fantasy blueprints of white men in Paris. A Marxism that mourns the horrors of capitalism but recoils in horror at its negation. In short, a Marxism that has become a boutique product of the theory industry: marketable, fashionable, and entirely compatible with empire.

And yet, the most damning part of Losurdo’s argument is not what he says about these thinkers—it’s what he reveals about their function. Western Marxism is not just wrong. It is structurally necessary to the reproduction of imperial ideology. It provides the moral alibi for the liberal intelligentsia. It allows professors, artists, and media personalities to posture as radicals while disciplining real revolutionaries. It is the velvet glove over the iron fist. The lecture series that justifies the drone strike. The footnote that buries the insurrection.

That is why this review—like Losurdo’s book—is not interested in academic debates about which school of thought better interprets Marx. We are interested in whether your theory serves the people who bleed. Whether your politics aligns with the factory worker in Vietnam, the farmer in Burkina Faso, the villager in Gaza. Or whether it serves the colonial metropole that pays your salary and rewards your cynicism with prizes, publications, and podcast slots.

Losurdo draws a clear line in the sand. And so do we. This is not a debate between competing theories. It is a class war inside Marxism itself. On one side: those who side with empire’s enemies, who engage with the contradictions of power, who see theory as a weapon. On the other: those who manufacture critique for imperial consumption. Who denounce revolution as authoritarianism, dismiss development as state capitalism, and reduce global class struggle to footnotes in their dissertation.

Which side are you on?

The Anticolonial Blindspot: When the West Refused to Learn from the World

At the heart of Losurdo’s indictment lies a truth so glaring that only Western Marxists could have ignored it: the greatest revolutionary achievements of the twentieth century did not happen in Paris, London, or New York. They happened in Havana, Hanoi, Beijing, and Algiers. And yet, for decades, the so-called radical intelligentsia of the West treated these uprisings not as the vanguard of socialist struggle, but as unfortunate deviations—quaint nationalisms, vulgar third worldisms, tragic detours from the “real” revolution that never quite managed to arrive on European soil. It’s not that they misunderstood anticolonial revolution. It’s that they actively disdained it. Losurdo’s phrase is sharp and unambiguous: it was “a meeting that didn’t happen.”

In chapter after chapter, Losurdo exposes the deranged mental gymnastics required to ignore the tidal wave of anticolonial victories that shook the world from 1945 to the 1980s. These weren’t isolated skirmishes—they were the most advanced forms of class struggle on the planet. The Vietnamese people humiliated the U.S. war machine. Algerian peasants defeated French fascism. The Chinese peasantry overthrew feudalism and imperial occupation in one of the most ambitious social transformations ever undertaken. And yet, while bombs fell and empires crumbled, the intellectuals of Europe were busy writing long essays on melancholy and the dialectic, wondering aloud whether real change was still possible.

But this was no accident. It was the result of a Eurocentric framework that saw revolution as a Western property, a dialectical entitlement of the white industrial proletariat. When revolutions erupted elsewhere—especially under peasant or nationalist leadership—they were derided as insufficiently Marxist. Too messy. Too violent. Too religious. Too populist. And above all, too successful. For a tradition built on fetishizing failure and romanticizing defeat, actual victory posed a philosophical crisis. Losurdo diagnoses it precisely: Western Marxism is only comfortable with the oppressed when they lose. The moment they seize power, build a state, or nationalize their resources, the Western left turns against them.

Consider this: Ho Chi Minh read Marx in Paris, studied Lenin in Moscow, and organized a communist movement in Southeast Asia under direct imperial occupation. He led his people in defeating both French and American colonial armies. But where is the legacy of Ho in Western theory? Where is Fanon? Where is Amílcar Cabral? Where is Sankara? These men died with a gun in one hand and The Communist Manifesto in the other, but they are treated by Western Marxists like exotic footnotes—if they’re mentioned at all. Meanwhile, Slavoj Žižek gets top billing at every book fair and lecture hall, despite having cheered on the privatization of Yugoslavia and supported NATO’s war in Ukraine. The message is clear: only the Marxism of the imperial center is permitted to think. Everything else must be explained away, dismissed, or ignored.

This is not just ideological arrogance—it is class treason. By refusing to take seriously the anticolonial revolutions of the twentieth century, Western Marxists revealed their loyalty to empire. They clutched their copies of Negative Dialectics while the U.S. dropped Agent Orange on rice fields. They waxed poetic about the “death of the subject” while socialist movements were building schools, electrifying villages, and collectivizing agriculture across Asia and Africa. They declared the Soviet Union a “bureaucratic nightmare” while Moscow trained thousands of doctors, engineers, and anti-imperialist militants from the Global South. They claimed to speak for the oppressed while mocking the only movements that ever actually freed them.

Losurdo doesn’t let them off the hook. He shows how Adorno’s contempt for revolutionary violence in the periphery mirrors Horkheimer’s bizarre defense of U.S. military interventions as protectors of “human rights.” He exposes Althusser’s posturing anti-humanism as an ideological cop-out that insulated the Western left from engaging with the messy realities of liberation struggles. He ridicules Negri and Hardt’s metaphysical babble about “Empire” while they erase the very real empire of NATO, IMF, and AFRICOM. And he decimates the romanticization of 1968, revealing how it functioned more as an anarcho-aesthetic tantrum than a revolutionary moment, disconnected from—and often hostile to—the movements of the colonized.

What Losurdo demands—and what Weaponized Information affirms—is a rupture with this parasitic tradition. We do not need more critiques of power from those who have never risked their lives in struggle. We need a return to the historical materialism that locates theory in the movements of the oppressed, not in the footnotes of the Frankfurt School. We need a Marxism that centers the plantation, the colony, the sweatshop, and the drone strike—not the lecture hall. And we need to be unapologetic in our defense of the socialist states and anti-imperialist revolutions that have fought, and continue to fight, to carve out spaces of survival against the barbarism of the West.

In this sense, Losurdo does not merely critique Western Marxism—he invites us to bury it. Not with sorrow, but with clarity. To acknowledge what it was: a class formation, an ideological buffer, a decadent tradition whose refusal to align with anticolonial revolution rendered it politically obsolete. Its death is not a tragedy. It is a necessity.

The Theory Industry and the CIA: Manufacturing the Compatible Left

To understand why Western Marxism became what it is, you have to follow the money. You have to map the institutions, the networks, the grants, the publishing deals. You have to examine who funds what, who gets translated, who gets tenure, who gets the platforms, and who gets purged. And when you do, you uncover the dirty secret at the core of Losurdo’s entire analysis: much of what we call “radical theory” in the imperial core was manufactured, curated, and subsidized to be just that—radical enough to seem dangerous, but harmless enough to never threaten power. This is not speculation. It’s historical fact. And Losurdo calls it by name: the compatible left.

This so-called left is the one that cries over Che Guevara’s diary but supports sanctions on Cuba. That mourns Walter Rodney but dismisses socialist China as “authoritarian.” That quotes Fanon in a thesis while opposing armed struggle in Palestine. The compatible left is the one that dances around imperialism while playing court jester to capital. And as Losurdo makes clear, it didn’t emerge by accident. It was built—deliberately, strategically, and with enormous investment—by the institutions of imperialism itself.

Enter the CIA. Not the boogeyman of conspiracy, but the historically documented architect of cultural warfare. Through fronts like the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA spent millions funding journals, university departments, literary prizes, art exhibitions, and philosophical movements across Europe and the Americas. Their goal was not simply to discredit the Soviet Union. It was to redefine the very meaning of leftism—to produce a “respectable socialism” that would denounce communism, reject anti-imperialist struggle, and remain permanently allergic to the seizure of power.

And it worked. Journals like Encounter, Der Monat, and Preuves published Adorno, Arendt, and other darlings of the anti-communist intelligentsia. Conferences promoted liberal “humanist” Marxism as a civilized alternative to Leninism. “Radical” thinkers who condemned U.S. policy were excluded. Those who condemned actually existing socialism were amplified. The Frankfurt School, which began as a radical analysis of capitalist domination, was integrated into the cultural counterinsurgency machine. Its quietist turn wasn’t just philosophical—it was political. Horkheimer supported U.S. intervention in Vietnam. Adorno had no time for revolutionary struggle, only for psychoanalysis and atonal music. These weren’t just bad takes. They were ideological positions that aligned with imperial interests.

And yet this entire operation succeeded in painting itself as critical. As radical. As Marxist. This is the genius of the theory industry—it packages submission as sophistication. It sells cowardice as complexity. It promotes a politics of resignation wrapped in the aesthetic of resistance. Losurdo lifts the veil on this intellectual theater and exposes the actors for what they are: salaried ideologues of empire. Their function is not to challenge power, but to manage dissent. Not to ignite revolution, but to exhaust it.

In a particularly scathing passage, Losurdo turns his attention to Žižek—the Slovenian philosopher who built an entire career on blasphemous provocation and carefully sanitized heresy. A man who came of age undermining socialism in Yugoslavia, campaigned for privatization, and later cheered NATO’s proxy wars—all while posing as a Marxist. Žižek, like others in his orbit, is a textbook case of what Losurdo calls the “radical recuperator”: someone who performs revolution while disarming it, who appropriates its language while sneering at its victories.

This is the cultural function of Western Marxism in the neoliberal order. It is not meant to organize workers. It is not meant to build parties. It is not meant to overthrow imperialism. It is meant to manage the imagination. To keep critique contained within the university, safely quarantined from struggle. And to ensure that any genuine attempt to build socialism—especially by non-Western people—will be met with moralistic condemnation from the left flank of the empire itself.

Losurdo’s brilliance lies in connecting the dots. He doesn’t just critique the content of Western Marxism. He locates its material basis. He exposes its patrons. He names the class that benefits from it. And he reminds us that in capitalism, even theory is a commodity—and the market pays best for that which justifies its own reproduction. This is why so many “radical” philosophers are invited to speak at NATO-sponsored forums while Cuban doctors are blocked from international conferences. It’s why the socialist governments of Venezuela or Nicaragua are demonized, while imperial technocrats in Davos are applauded for their “concern about inequality.” It’s why decolonial studies flourishes in the academy, but revolutionary anti-imperialism is still met with silence or scorn.

What Losurdo offers is not nostalgia for Soviet orthodoxy or a demand for intellectual conformity. He offers something far more dangerous: a call to reconnect theory to struggle. To build a Marxism that is accountable not to citation metrics or grant committees, but to the masses of the world. A Marxism that does not speak about the oppressed, but speaks with them—and fights for them.

This is our task as revolutionaries. To tear the mask off the theory industry. To expose the NGO-ification of the left. To destroy the idea that “radical” means unreadable jargon and performative irony. And to return to the truth that theory, if it is not a weapon, is a luxury of the ruling class.

Rebellion as Style, Revolution as Crime: The Messianic Drift of Western Marxism

One of the most damning contributions of Losurdo’s book is his unsparing critique of the aestheticization of rebellion that saturates Western Marxism. In the hands of the imperial intelligentsia, revolution is not a process, not a dialectic of seizure and construction—but a performance. A vibe. A mood. Stripped of strategy, severed from mass struggle, rebellion becomes a consumer affect: the leather jacket of politics. You can wear it, tweet it, quote it—but you never have to win with it. Because winning, in this ideology, is betrayal.

Losurdo names this tendency “messianism”—a theological inheritance masquerading as radicalism. At its core is the idea that the revolution must arrive like a lightning bolt from the heavens. Pure. Unstained. Absolute. It cannot grow, struggle, stumble, or adapt. It cannot build hospitals or ministries. It cannot negotiate contradictions. It must rupture everything. And so, the very messiness of real revolutions—Lenin’s NEP, Mao’s rural industrialization, Fidel’s alliance with Black radicals, Sankara’s land reforms—disqualifies them. They are sullied by reality. Impure. Tainted by the sin of power.

That’s why Western Marxism loves the rebel but fears the revolutionary. It adores the moment before power is seized, but condemns what comes after. It celebrates uprising as catharsis but recoils from construction as compromise. Losurdo makes the comparison explicit: it’s Christianity in disguise. Badiou’s “Event,” Žižek’s “Act,” the cult of 1968, the permanent fetish of failure—all of it is infused with messianic longing for a rupture that transcends history, delivers grace, and spares us from responsibility. It is, quite literally, the religion of the petty bourgeoisie: salvation without sacrifice, transformation without work, communion without commitment.

But the Global South has no time for these fantasies. When imperialism is at your throat and hunger is knocking at your door, you don’t wait for the Messiah. You organize. You take land. You nationalize. You make mistakes and learn from them. You build the people’s army, the people’s clinic, the people’s education. You take power and defend it. And if you have to deal with bureaucracy, contradictions, and enemies inside and out, so be it. That’s the price of revolution. But in the West, where theory is protected by tenure and failure is rewarded with book deals, the idea of revolution is romanticized precisely because it never arrives. It is a ghost story told by those who fear the living.

This messianic drift also enables the rejection of any socialist project that does not conform to the aesthetic expectations of the Euro-left. They reject China because it’s too pragmatic. Cuba because it negotiates. Vietnam because it trades. They want revolutions that don’t defend themselves, parties that don’t discipline, movements that don’t make decisions. They want to have communism without the state, equality without development, and struggle without war. What they refuse to admit is that this dream is not revolutionary—it’s imperial. It is the expectation that the oppressed will deliver liberation to the West in the form of spectacle, without ever threatening its material privileges.

Losurdo rips this fantasy to shreds. He reminds us that Marx and Engels never wrote that the revolution would be perfect. They wrote that it would be material. Historical. Born in blood and contradiction. They understood that socialism would arise not from the mind of the philosopher, but from the muck and fire of collective struggle. And that the task was not to imagine a new world from scratch, but to transform the existing one, with all its weight, violence, and potential. As they put it in The German Ideology: “Communism is not a state of affairs to be established, an ideal to which reality will have to adjust. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.”

That movement does not come from critique. It comes from power. From organizing. From revolutionaries who seize the means of production, dismantle the imperial state, and set in motion a new mode of life. And yes, they will make mistakes. So did the Paris Commune. So did the Soviets. So did every people who ever fought back. But the question is not whether they lived up to your fantasy. The question is whether they advanced the struggle against exploitation and empire. Whether they put the poor in charge. Whether they changed the world in the name of the oppressed. And if the answer is yes, then you do not condemn them—you learn from them.

The Western left needs to grow up. It needs to stop worshipping rebellion like a fetish and start building the political infrastructure needed for liberation. It needs to shed its messianic delusions and confront the hard, disciplined work of revolutionary organization. It needs to bury the ghost of 1968 and study 1949, 1959, 1975. And most of all, it needs to understand that the future will not be made by philosophers. It will be made by the people—their victories, their contradictions, their sovereignty.

Losurdo’s critique is not gentle, and it is not designed to comfort. It is designed to clarify. He is not offering a better theory. He is offering a better side. And his question echoes through every page of this book like a thunderclap: Are you with the empire and its court jesters? Or are you with the people, building power brick by brick, with blood in the mortar?

Resurrecting Marxism in the Belly of the Beast

What, then, remains for those of us trapped in the imperial core? For those of us surrounded by the glittering ruins of Western Marxism, where theory has become a burial ground and solidarity is often just a hashtag? Losurdo doesn’t end with despair—he ends with a call to arms. And not the empty call of slogans and LARPing revolts, but the disciplined invitation to rebuild Marxism in the West—not as a theoretical school, not as a fashion statement, but as a weapon in the hands of the people. This is not revivalism. It is insurgency. It is counterinsurgency against the ideological counterinsurgency that has passed for leftist thought for half a century.

For Marxism to be reborn in the West, Losurdo insists, it must do the thing Western Marxists have refused to do for generations: learn from the Global South. Not extract concepts, not borrow vibes, not romanticize failures—but actually study the successes, understand the contradictions, and join the world-historical project of decolonization and socialism. It must recognize that the core of the class struggle today is not in Berlin or Berkeley—it is in Accra, Caracas, Shenzhen, Ramallah, and Soweto. That’s where the global proletariat is fighting and building. That’s where power is being contested. That’s where Marxism lives.

To realign with this struggle, Western Marxism must undergo a ruthless ideological detox. It must expel the parasite of Eurocentrism, abandon its addiction to moralism, and sever its unholy alliance with liberalism and imperial technocracy. It must renounce its fetish for rebellion and embrace the reality of revolution. It must drop its cult of critique and learn what it means to be useful to movements that actually intend to win. As Losurdo reminds us, the test of theory is not its novelty, but its utility in advancing liberation. Not how many citations it has, but how many prisons it breaks, how many famines it ends, how many guns it forces the empire to lay down.

This means returning to the Leninist principle of practice as the criterion of truth. It means rebuilding organizations rooted in working-class struggle, particularly among the colonized, racialized, and hyper-exploited sections of the class. It means forging a principled internationalism that sides with the resistance in Gaza, the revolutionaries in the Philippines, the land defenders in Colombia, the socialists in Mali, the survivors in Haiti, and the builders in China—not as allies, but as comrades in a shared global war against capital and empire.

But it also means organizing in the imperial core itself. Not retreating into academic detachment or nihilist apathy, but building revolutionary instruments that can crack open the soft underbelly of the beast. It means confronting the class contradictions within the settler colonial working class, exposing the labor aristocracy, and naming the material wages of whiteness and empire that buy loyalty and blunt solidarity. It means fighting for a revolutionary rupture that does not just seek reform, but rupture—on behalf of those whom this system devours.

This is not glamorous work. It’s not as sexy as publishing a new interpretation of Adorno or another reinvention of the dialectic. But it’s the work of revolution. It is the task of breaking with the compatible left and forging a line of demarcation between those who serve the oppressed and those who serve themselves. Losurdo makes it clear: the rebirth of Marxism in the West can only happen by aligning ourselves, materially and politically, with the anticolonial, anti-imperialist front of the global proletariat. Anything less is capitulation.

It is here that Weaponized Information plants its flag. We are not interested in theory for theory’s sake. We are interested in the theory that builds power, dismantles empire, and trains the class to think like a ruling class in formation. We are here to bury the dead, rescue the living, and arm the future. If that means rejecting the pantheon of the Western Marxist canon, so be it. If that means standing with the maligned revolutions of the South against the polite condemnation of Western intellectuals, so be it. If that means building underground when there’s no stage left to stand on, so be it.

Losurdo’s final gift to us is not a new theory—it is clarity. Clarity about where we are, who we are up against, and what must be done. The West will not save Marxism. It never did. But from within its rotting carcass, revolution can still grow—if we have the discipline to unlearn, the humility to follow, and the courage to fight.

Class War in Theory: Choose Your Side

This book is not a mirror—it’s a blade. Losurdo doesn’t want your admiration. He wants your defection. From the ideology of critique to the politics of power. From the melancholia of the West to the rebellion of the South. From a Marxism that performs radicalism to a Marxism that wages war. If you came here looking for an intellectual review, you’re in the wrong place. This is a line of demarcation. This is theory in uniform.

We are not interested in the debates that dominate the seminar rooms of decaying empires. Whether Adorno was more refined than Althusser, whether Gramsci can be safely neutralized by liberal cultural studies, whether Foucault’s whispers about power can substitute for a rifle in the hands of the oppressed. These are not our questions. Our question is this: does your theory take the side of the colonized, the exploited, the revolutionaries of the earth—or does it stand in the way?

Because that’s what’s at stake. In a world hurtling toward climate apocalypse and nuclear annihilation, there is no neutral ground. Your critique of China is not brave if you can’t name the U.S. empire. Your concern about authoritarianism is meaningless if you ignore the hunger embargoes, drone wars, and IMF strangleholds imposed by the liberal world order. Your Marxism is hollow if it cannot recognize the construction of socialism in the Global South as the single most important project of human emancipation in the modern era.

Losurdo’s final lesson is Lenin’s first: you must name the class enemy. Not abstractly, but concretely. That means naming NATO, the U.S. war machine, the ruling class foundations funding academia, the billionaire donors behind the compatible left, and the managers of despair who publish defeat as wisdom. It means refusing the rituals of “balance” and the academic fetish for complexity that paralyzes commitment. It means choosing the barricade over the bookshelf, the commune over the column, the cadre over the critic.

In 1918, while imperialist armies tried to crush the Bolshevik newborn, Lenin didn’t write poetry. He wrote The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky. He understood that the battlefield of theory is not a sideshow—it’s the ideological front of the class war. Losurdo picks up that banner. And now we must pick it up too. Against the opportunists. Against the careerists. Against the sadness merchants who sell paralysis in the language of radical skepticism. Against the whole rotting structure of Western Marxism that tried to make peace with power.

Let us be clear. The future is not written by think pieces. It is written in trenches and classrooms, prisons and parliaments, factories and fields. And in every one of these arenas, the question echoes: which side are you on? Losurdo does not ask us to answer with words. He asks us to answer with action. With alignment. With discipline. With struggle. That is how Marxism will be reborn—not through citation indexes or conference panels, but through commitment to the global war against imperialism and capitalism.

This is the class war in theory. This is the trench inside the mind. This is Weaponized Information. Choose your side.

Comments are closed.