This essay, written well before the commencement of the war, is adapted from Behind the Invasion of Iraq by the Research Unit for Political Economy, now available from Monthly Review Press. Footnotes providing full documentation are included in the book.

Three themes stand out in Iraq’s history over the last century, in the light of the present U.S. plans to invade and occupy that country.

First, the attempt by imperialist powers to dominate Iraq in order to grab its vast oil wealth. In this regard there is hardly a dividing line between oil corporations and their home governments, with the governments undertaking to promote, secure, and militarily protect their oil corporations.

Second, the attempt by each imperialist power to exclude others from the prize.

Third, the vibrancy of nationalist opposition among the people of Iraq and indeed the entire region to these designs of imperialism. This is manifested at times in mass upsurges and at other times in popular pressure on whomever is in power to demand better terms from the oil companies or even to expropriate them.

The following account is limited to Iraq, and it provides only the barest sketch.

From Colony to Semi-Colony

Entry of Imperialism

Iraq, the easternmost country of the Arab world, was home to perhaps the world’s first great civilization. It was known in classical times as Mesopotamia (“Land between the Rivers”—the Tigris and the Euphrates), and became known as Iraq in the seventh century. For centuries Baghdad was a rich and vibrant city, the intellectual center of the Arab world. From the sixteenth century to 1918, Iraq was a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, divided into three vilayets (provinces): Mosul in the north, Baghdad in the center, and Basra in the south. The first was predominantly Kurdish, the second predominantly Sunni Arab, and the third predominantly Shiite Arab.

As the Ottoman Empire fell into decline, Britain and France began extending their influence into its territories, constructing massive projects such as railroads and the Suez Canal and keeping the Arab countries deep in debt to British and French banks.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Britain directly ruled Egypt, Sudan, and the Persian Gulf, while France was the dominant power in Lebanon and Syria. Iran was divided between British and Russian spheres of influence. The carving up of the Ottoman territories (from Turkey to the Arabian peninsula) was on the agenda of the imperialist powers.

When Germany, a relative latecomer to the imperialist dining table, attempted to extend its influence in the region by obtaining a “concession” to build a railway from Europe to Baghdad, Britain was alarmed. By this time the British government—in particular its navy—had realized the strategic importance of oil, and it was thought that the region might be rich in oil. Britain invested A32.2 million in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (a fully British firm operating in Iran) to obtain a 51 percent stake in the company. Gulbenkian, an adventurous Armenian entrepreneur, argued that there must be oil in Iraq as well. At his initiative the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) was formed: 50 percent British, 25 percent German, and 25 percent Royal Dutch-Shell (Dutch- and British-owned).

The First World War (1914–1918) underlined for the imperialists the importance of control of oil for military purposes, and hence the urgency of controlling the sources of oil. As soon as war was declared with the Ottomans, Britain landed a force (composed largely of Indian soldiers) in southern Iraq, and eventually took Baghdad in 1917. It took Mosul in November 1918, in violation of the armistice with the Turks a week earlier.

During the war, the British carried on two contradictory sets of secret negotiations. The first was with Sharif Husayn of Mecca. In exchange for Arab revolt against Turkey, the British promised support for Arab independence after the war. However, the British insisted that Baghdad and Basra would be special zones of British interest where “special administrative arrangements” would be necessary to “safeguard our mutual economic interests.”

The second set of secret negotiations, in flagrant violation of the above, was between the British and the French. In the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, Iraq was carved up between the two powers, with the Mosul vilayet going to France and the other two to Britain. For its assent, czarist Russia was to be compensated with territory in northeast Turkey. When the Bolshevik revolutionaries seized power in November 1917 and published the czarist regime’s secret treaties, including the Sykes–Picot Agreement, the Arabs learned how they had been betrayed.

Iraq Under British Rule

After the war, the spoils of the German and Ottoman empires were divided among the victors. Britain’s promises during the war that Arabs would get independence were swiftly buried. France got the mandate for Syria and Lebanon, and Britain got the mandate for Palestine and Iraq. (The “mandate” system, a thin disguise for colonial rule, was created under the League of Nations, the predecessor to today’s United Nations. Mandate territories, earlier the possessions of the Ottomans, were to be “guided” by the victorious imperialist powers until they had proved themselves capable of self-rule.)

Britain threatened to go to war to ensure that Mosul province, which was known to contain oil, remained in Iraq. The French conceded Mosul in exchange for British support of French dominance in Lebanon and Syria and a 25 percent French share in TPC.

However, anti-imperialist agitation in Iraq troubled the British from the start. In 1920, with the announcement that Britain had been awarded the mandate for Iraq, revolt broke out against the British rulers and became widespread. The British suppressed the rebellion ruthlessly—among other things bombing Iraqi villages from the air (as they had done a year earlier to suppress the Rowlatt agitation in the Punjab). In 1920, Secretary of State for War and Air Winston Churchill proposed that Mesopotamia “could be cheaply policed by aircraft armed with gas bombs, supported by as few as 4,000 British and 10,000 Indian troops,” a policy formally adopted at the 1921 Cairo conference.

The British Install a Ruler

Shaken by the revolt, the British felt it wise to put up a facade. (In the words of Curzon, the foreign secretary, Britain wanted in the Arab territories an “Arab facade ruled and administered under British guidance and controlled by a native Mohammedan and, as far as possible, by an Arab staff….There should be no actual incorporation of the conquered territory in the dominions of the conqueror, but the absorption may be veiled by such constitutional fictions as a protectorate, a sphere of influence, a buffer state and so on.”) The British High Commissioner proclaimed Emir Faisal I, belonging to the Hashemite family of Mecca, which had been expelled from the French mandate Syria, as the King of Iraq. The puppet Faisal promptly signed a treaty of alliance with Britain that largely reproduced the terms of the mandate. This roused such strong nationalist protests that the cabinet was forced to resign, and the British High Commissioner assumed dictatorial powers for several years. Nationalist leaders were deported from the country on a wide scale. (In this period the whole region was in ferment, with anti-imperialist struggles emerging in Palestine and Syria as well.) The British also drafted a constitution for Iraq that gave the King quasi-dictatorial powers over the Parliament.

In 1925, widespread demonstrations in Baghdad for complete independence delayed the treaty’s approval by the Constituent Assembly. The High Commissioner could only force ratification by threatening to dissolve the assembly. Even before the treaty of alliance was ratified—and before there was even the facade of an Iraqi government—a new concession was granted to the Turkish Petroleum Company for the whole of Iraq, in the face of widespread opposition and the resignation of two members of the cabinet. (Among other things, the British blackmailed Iraq by threatening that, in the negotiations with the Turks, they would cede the oil-rich northern province of Mosul to neighboring Turkey—the opposite of what they were demanding in the earlier-mentioned negotiations with the French. Thus even the borders of the countries in these regions were set at the convenience of imperialist exploitation. The worst sufferers were the Kurds, whose territory was divided by the imperialist powers among southern Turkey, northern Syria, northern Iraq, and northwestern Iran.)

The terms of the concession, covering virtually the entire country until the year 2000, were outrageous. Payment was four shillings (one-fifth of a British pound) per ton of oil produced. For this extraordinary giveaway, the puppet king Faisal received a personal present of A340,000. It was this concession that the oil corporations, for half a century thereafter, would fight to defend as their “legitimate” right.

Contention for Oil

With Germany’s defeat in the war, its stake in the Turkish Petroleum Company fell into Britain’s lap. Thus Britain would almost completely dominate the company. However, this was no longer tenable following the new correlation of the strengths of the different imperialist powers. Britain, though it had the largest empire among the imperialist powers, was actually in decline. Unable now to compete with other industrial economies, it desperately attempted to use its exclusive grip over its colonies to shore up its economic strength; whereas the United States, now the leading capitalist power, demanded what it termed an “open door” to exploit the possessions of the older colonizing powers. Two years after the end of the First World War, Woodrow Wilson, the U.S. president, wrote:

It is evident to me that we are on the eve of a commercial war of the severest sort and I am afraid that Great Britain will prove capable of as great commercial savagery as Germany has displayed for so many years in her commercial methods. (Joe Stork, Middle East Oil and the Energy Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1975, p. 14.)

American oil companies, with U.S. government backing, demanded a share in the Turkish Petroleum Company, and by 1928 two American companies, Jersey Standard and Socony (later known as Exxon and Mobil, and today as the merged Exxon-Mobil) got a 23.75 percent stake, on par with the British, French, and Royal Dutch-Shell interests. Most of the major oil corporations in the world were thus represented in the Turkish Petroleum Company (now renamed the Iraq Petroleum Company—hereafter IPC).

Contending with Nationalism

The continuous local opposition to British rule at last forced Britain to grant Iraq “independence” in 1932. But this Britain did only after extracting a new treaty stipulating a “close alliance” between the two countries and a “common defense position”, continued indirect rule by the British. Britain kept its bases at Basra and west of the Euphrates, and Faisal continued to occupy the Iraqi throne.

Even such “independence” did not last long. In 1941, sections in the Iraqi army and political parties staged a coup against the king and were about to ally with the Axis powers to win freedom from the British. Britain invaded Iraq once again and occupied it, installing once again the king and a puppet cabinet headed by their lapdog Nuri as-Said (who was made prime minister fourteen times in the turbulent period 1925–1958).

After the war ended in 1945, British occupation continued. Martial law was declared in order to crush protests against the developments in Palestine in 1948 (the driving out of the Palestinians and the seizure of their lands by the new Zionist state). Just then, the Iraqi government signed a new treaty of alliance with Britain, whereby Iraq was not to take any step in foreign policy contrary to British directions. A joint British-Iraqi defense board was to be set up. But when the prime minister returned from London after having concluded this deal, a popular uprising took place in Baghdad, forcing his resignation and the repudiation of the treaty. In the following years, nationalist forces demanded nationalization of the oil industry (as Iran had carried out in 1951).

In 1952 another popular uprising occurred, carried out by students and “extremists.” The police were unable to control the demonstrators, and the regent called on the army to maintain public order. The chief of the armed forces general staff governed the country under martial law for more than two months. All political parties were suppressed in 1954.

Growing U.S. Intervention in the Region

The price of standing up to the oil corporations was made clear in neighboring Iran. There, the regime headed by Mossadeq nationalized British Petroleum in 1951, and after a devastating boycott by all the oil giants for the next two years, was overthrown by a CIA-led coup in 1953. (The CIA man in charge of the operation later became vice-president of Gulf Oil.)

On the other hand, regimes throughout the region were under pressure from the Arab masses. Gamal Abdul Nasser, who came to power in Egypt in a 1952 coup, adopted a confrontational posture toward the United States and Britain, nationalizing the Suez Canal and taking assistance from the Soviet Union. Nasser’s stance won him popular support in the Arab world, where Iraq and Egypt contended for leadership. In that period an anti-imperialist wave swept the Arab countries, threatening the stability of pro-Western puppet regimes.

The United States became the new gendarme of the region to suppress any agitation against imperialism and its client states. For example, when in 1953 both Saudi Arabia and Iraq crushed oil workers’ strikes by the use of troops and martial law regimes, shipments of arms from the United States to both followed immediately. In 1957 the Jordanian king (the first cousin of the Iraqi king) arrested his prime minister, dissolved the parliament, outlawed political parties, and threw his opponents into concentration camps, with economic and military aid from the United States. In 1958 the right-wing Lebanese regime used American equipment in its attempt to crush nationalist opposition. At American insistence three pro-U.S.-U.K. regimes—Iraq, Turkey, and Pakistan—came together to form an alliance against the USSR, the Baghdad Pact (later known as the Mideast Treaty Organization and the Central Treaty Organization; Britain and Iran joined subsequently). Iraq, the only Arab country to join this pact, had to face Nasser’s denunciation for doing so.

Toward Nationalization

In July 1958 an army faction led by Abdel Karim Qasim seized power in Iraq, executed the king and Nuri as-Said, and declared a republic to wide public acclaim. This was the first overthrow of a puppet regime in an oil-producing country. The new regime appealed to the popular anti-imperialist consciousness in its very first announcement: “With the aid of God Almighty and the support of the people and the armed services, we have liberated the country from the domination of a corrupt group which was installed by imperialism to lull the people.”

The United States and the U.K. immediately moved their troops to Lebanon and Jordan respectively in preparation to invade Iraq. Unfortunately for the United States, the deposed regime was so widely despised in Iraq that no force could be found to assist the American plan. Nevertheless, the United States delivered an ultimatum threatening intervention if the new regime did not respect its oil interests. The coup leaders for their part issued repeated declarations that these interests would in fact not be touched. Only then were American and British troops withdrawn. Thus Iraq is no stranger to the threat of imperialist invasion.

Popular Pressure and the Companies’ Counterattack

Despite its assurances to the Americans, the new Iraqi regime remained subject to popular pressure. The Iraqi masses expected the downfall of the puppet king to result in a renegotiation or scrapping of the colonial-era oil concession to the IPC. (According to Michael Tanzer, the total investment made by the oil companies in Iraq was less than $50 million—after this they received profits sufficient to finance all future investment; whereas Joe Stork calculates their profits from Iraq at $322.9 million in 1963 alone.) Even Iran and Saudi Arabia had obtained better terms than Iraq because their earlier concessions did not cover their entire territories, whereas IPC owned the entire territory of Iraq.

However, the owners of IPC, principally the American and British oil giants, owned fields elsewhere in the world as well, and it was not the cost of production but complex strategic considerations that determined which fields they would exploit first. They were in no hurry to develop the Iraqi fields or build larger refining capacity there—IPC’s existing installations covered only 0.5 percent of its concession area. When the Qasim regime demanded that the IPC give up 60 percent of its concession area, double output from existing installations and double refining capacity, the IPC responded by reducing output. The oil giants had decided to make an example of Iraq, to prevent any other oil-producing country from showing backbone.

Qasim responded to the oil giants’ intransigence by withdrawing from the Baghdad Pact, withdrawing from the sterling bloc, signing an economic and technical aid deal with the Soviet Union in 1959, ordering British forces out of Habbaniya base, and canceling the American aid program. In 1961 he wound up negotiations with the IPC and issued Law 80, under which the IPC could continue to exploit its existing installations, but the remaining territory (99.5 percent) would revert to the government.

The oil giants responded by further suppressing IPC production. In turn, Qasim in 1963 announced the formation of a new state oil company to develop the non-concession lands, and revealed an American note threatening Iraq with sanctions unless he changed his position. He was overthrown four days later in a coup that the Paris weekly L’Express stated flatly was “inspired by the CIA.”

1963 Coup and the IPC Negotiations

The coup was carried out by an alliance between the Ba’ath Party (full form: Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party; Ba’ath means “renaissance”) and an army faction, but the Ba’ath was soon ejected from power by its partners in the coup. The new rulers promptly granted the IPC another 0.5 percent of the concession area, including the rich North Rumaila field, which the IPC had discovered but failed to exploit. IPC agreed to enter a joint venture with the new Iraq National Oil Company (INOC) to explore and develop a large portion of the expropriated area as well.

The agreement, however, was condemned by Arab nationalist opinion, and the regime hesitated for years to ratify it. Meanwhile the Arab-Israeli War, in which Iraq participated, broke out in 1967. Israel, with American backing, seized and occupied lands belonging to Syria, Egypt, and Jordan. Diplomatic ties between Iraq and the United States were broken. The strength of anti-American and anti-British sentiment after the 1967 War made it impossible for the Iraqi regime to return North Rumaila to the IPC. The Iraqi government instead issued Law 97, whereby the INOC alone would develop oil in all but the 0.5 percent still conceded to the IPC.

Between 1961 and 1968, IPC increased production in Iraq by only a fraction of the increase achieved in the docile regimes of Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia by the same oil giants who owned IPC. Since the size of IPC’s payments to the Iraqi government depended on the size of its oil output, and since the government’s revenues depended heavily on these payments, the oil giants’ tactic caused Iraq great financial stringency, and prevented it from undertaking developmental projects. According to a secret U.S. government report, the IPC actually drilled wells to the wrong depth and covered others with bulldozers in order to reduce productive capacity. The prolonged deadlock had extracted a great price: “more than a dozen years of economic stagnation, political instability, and confrontation.”

Saddam Hussein Comes to Power

The Ba’ath party returned to power in a 1968 coup (in which Saddam Hussein became vice president, deputy head of the Revolutionary Command Council, and increasingly the real power), and that party continued the course toward extricating the oil industry from the grip of the IPC. Finally in 1972 the IPC was nationalized, its shareholders paid a compensation of $300 million (effectively offset by company payment of $345 million in back claims). The country turned to France and the Soviet Union for technical assistance and credit. The Soviets developed the North Rumaila field more or less on schedule by 1972.

For the Soviets, Iraq was an important breakthrough in the region: Iraq had vast oil reserves, unlike Egypt and Syria with whom the Soviets had ties (they were ejected from the former in 1972). It thus yielded lucrative oil contracts, investments in Eastern Europe from its oil surpluses, massive arms sales, and the promise of greater Soviet influence in the region. France, too, maintained ties with Iraq’s oil industry. (Significantly, despite the overwhelming importance of oil to Iraq’s economy, and the heavy price of its dependence on foreign firms, the country did not bring about the level of technological self-reliance in this field that socialist China did during the same years. Rather, it merely attempted to loosen the bonds to the U.S.-U.K. oil giants by tying up with other advanced countries.)

The Iraqi nationalization took place against the background of increasing assertion by even pro-U.S. regimes in the region. Radical Arab oil experts (most prominently Abdullah Tariki) gripped the popular imagination with their well-documented exposures of how the oil wealth of the Arab lands was being looted; the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) actively demanded better terms for their oil; a group of young army officers led by Muammar Qaddafi overthrew the Libyan monarchy in 1969 and called for confrontation with the oil giants; and the armed Palestinian struggle was born. The defeat of the Arab armies in the 1973 war with Israel further stoked anti-American sentiment. The process culminated with an Arab oil embargo against the Western states and a massive increase in prices paid to oil producing countries. Iraq, as a major oil producer (with the world’s second-largest reserves, after Saudi Arabia), played a crucial role in mounting this challenge.

Until the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, Iraq remained largely agricultural. It was only after the removal of the puppet king that year that some developmental projects were undertaken. After 1973, reaping the benefits of higher oil prices, the state’s welfare expenditures increased considerably. The supply of housing greatly increased, and living standard improved considerably. However, the regime went further, initiating a wide range of projects for industrial diversification, reducing the imports of manufactured goods, increasing agricultural production and reducing agricultural imports, and substantially increasing non-oil exports. Large investments were made in infrastructure, particularly in water projects, roads, railways, and rural electrification. Technical education was greatly expanded, training a generation of qualified personnel for industry.

These measures stood in striking contrast to the Gulf sheikhdoms of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. In those countries, a part of the huge increase in earnings after 1973 was spent on improving the standard of living of the kings’ subjects; the rest was invested in foreign banks and foreign treasury bills, principally American. Thus the United States was not fundamentally threatened by the oil price hike: while it paid higher oil prices, most of the extra funds flowed back to its own financial sector. Iraq, by contrast, invested far more of its oil revenues internally than other Arab states, and therefore had the most diversified economy among them.

It is worth noting that Iraq’s cultural climate and progress in certain areas of social life are abhorred by Islamic fundamentalists. Until 1991, literacy grew rapidly in Iraq, including among women. Iraq is perhaps the freest society in the entire region for women, and women are to be found in several professions.

In 1979, Saddam, already effectively the leader of Iraq, became president and chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. The entire region stood at a critical juncture.

For one thing, the pillar of the United States in West Asia, the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran, was overthrown by a massive popular upsurge that the United States was powerless to suppress. This made the United States and its client states deeply anxious at the prospect of similar developments taking place throughout the region.

For another, in Iraq Saddam had drawn on the country’s oil wealth to carry out a major military buildup, with military expenditures swallowing 8.4 percent of GNP in 1979. Starting in 1958 Iraq had become an increasingly important market for sophisticated Soviet weapons and was considered a member of the Soviet camp. In 1972, Iraq signed a fifteen-year friendship, cooperation, and military agreement with the USSR. The Iraqi regime was striving to develop or acquire nuclear weapons. Apart from Israel, the only army in the region to rival Iraq’s was Iran’s. But after 1979, when the Shah of Iran was overthrown, much of the Iranian army’s American equipment became inoperable.

The Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980 (on the pretext of resolving border disputes) thus solved two major problems for the United States. Over the course of the following decade two of the region’s leading military powers, neither of them hitherto friendly to the United States, were tied up in an exhausting conflict with each other. Such conflicts among third world countries create a host of opportunities for imperialist powers to seek new footholds, as happened also in this instance.

Despite its strong ties to the USSR, Iraq turned to the West for support in the war with Iran. This it received massively. As Saddam Hussein later revealed, the United States and Iraq decided to reestablish diplomatic relations—broken off after the 1967 war with Israel—just before Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980 (the actual implementation was delayed for a few more years in order not to make the linkage too explicit). Diplomatic relations between the United States and Iraq were formally restored in 1984—well after the United States knew, and a UN team confirmed, that Iraq was using chemical weapons against the Iranian troops. (The emissary sent by U.S. president Reagan to negotiate the arrangements was none other than the present U.S. defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld.) In 1982, the U.S. State Department removed Iraq from its list of “state sponsors of terrorism,” and fought off efforts by the U.S. Congress to put it back on the list in 1985. Most crucially, the United States blocked condemnation of Iraq’s chemical attacks in the UN Security Council. The United States was the sole country to vote against a 1986 Security Council statement condemning Iraq’s use of mustard gas against Iranian troops—an atrocity in which it now emerges the United States was directly implicated (as we shall see below).

Brisk trade was done in supplying Iraq. Britain joined France as a major source of its weapons. Iraq imported uranium from Portugal, France, and Italy, and began constructing centrifuge enrichment facilities with German assistance. The United States arranged massive loans for Iraq’s burgeoning war expenditure from American client states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. The U.S. administration provided “crop-spraying” helicopters (to be used for chemical attacks in 1988), let Dow Chemicals ship its chemicals for use on humans, seconded its air force officers to work with their Iraqi counterparts (from 1986), and approved technological exports to Iraq’s missile procurement agency to extend the missiles’ range (1988). In October 1987 and April 1988 U.S. forces themselves attacked Iranian ships and oil platforms.

Militarily, the United States not only provided Iraq with satellite data and information about Iranian military movements, but, as former U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) officers have recently revealed to the New York Times, they also prepared detailed battle planning for Iraqi forces in this period—even as Iraq drew worldwide public condemnation for its repeated use of chemical weapons against Iran. According to a senior DIA official, “If Iraq had gone down it would have had a catastrophic effect on Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and the whole region might have gone down—that was the backdrop of the policy.”

One of the battles for which the United States provided battle-planning packages was the Iraqi capture of the strategic Fao peninsula in the Persian Gulf in 1988. Since Iraq eventually relied heavily on mustard gas in the battle, it is clear the United States battle plan tacitly included the use of such weapons. DIA officers undertook a tour of inspection of the Fao peninsula after Iraqi forces successfully retook it, and they reported to their superiors on Iraq’s extensive use of chemical weapons, but their superiors were not interested. Col. Walter P. Lang, senior DIA officer at the time, says that “the use of gas on the battlefield by the Iraqis was not a matter of deep strategic concern.” The DIA, he claimed, “would have never accepted the use of chemical weapons against civilians, but the use against military objectives was seen as inevitable in the Iraqi struggle for survival.” (As we shall see below, chemical weapons were used extensively by the Iraqi army against Kurdish civilians, but DIA officers deny they were “involved in planning any of the military operations in which these assaults occurred.”) In the words of another DIA officer, “They [the Iraqis] had gotten better and better” and after a while chemical weapons “were integrated into their fire plan for any large operation.” A former participant in the program told the New York Times that senior Reagan administration officials did nothing to interfere with the continuation of the program. The Pentagon “wasn’t so horrified by Iraq’s use of gas,” said one veteran of the program. “It was just another way of killing people—whether with a bullet or phosgene, it didn’t make any difference,” he said. The recapture of the Fao peninsula was a turning point in the conflict, bringing Iran to the negotiating table.

A U.S. Senate inquiry in 1995 accidentally revealed that during the Iran-Iraq war the United States had sent Iraq samples of all the strains of germs used by the latter to make biological weapons. The strains were sent by the so-called Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Type Culture Collection to the same sites in Iraq that UN weapons inspectors later determined were part of Iraq’s biological weapons program.

It is ironic to hear the United States today talk of Saddam Hussein’s attacks on the Kurds in 1988. These attacks had their full support:

As part of the Anfal campaign against the Kurds (February to September 1988), the Iraqi regime used chemical weapons extensively against its own civilian population. Between 50,000 and 186,000 Kurds were killed in these attacks, over 1,200 Kurdish villages were destroyed, and 300,000 Kurds were displaced….The Anfal campaign was carried out with the acquiescence of the West. Rather than condemn the massacres of Kurds, the United States escalated its support for Iraq. It joined in Iraq’s attacks on Iranian facilities, blowing up two Iranian oil rigs and destroying an Iranian frigate a month after the Halabja attack. Within two months, senior U.S. officials were encouraging corporate coordination through an Iraqi state-sponsored forum. The United States administration opposed, and eventually blocked, a U.S. Senate bill that cut off loans to Iraq. The United States approved exports to Iraq of items with dual civilian and military use at double the rate in the aftermath of Halabja as it did before 1988. Iraqi written guarantees about civilian use were accepted by the United States commerce department, which did not request licenses and reviews (as it did for many other countries). The Bush administration approved $695,000 worth of advanced data transmission devices the day before Iraq invaded Kuwait (Alan Simpson, MP & Dr. Glen Rangwala, “The Dishonest Case for War on Iraq,” Labour Against the War Counter-Dossier, September 2002).

The full extent of U.S. complicity in Iraq’s “weapons of mass destruction” programs became clear in December 2002, when Iraq submitted an 11,800-page report on these programs to the UN Security Council. The United States insisted on examining the report before anyone else, even before the weapons inspectors, and promptly insisted on removing 8,000 pages from it before allowing the nonpermanent members of the Security Council to look at it. Iraq apparently leaked the list of American companies whose names appear in the report to a German daily, Die Tageszeitung. Apart from American companies, German firms were heavily implicated. (Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons, like his suppression of internal opposition, has been continuously useful to U.S. interests: condoned and abetted during periods of alliance between the two countries, it is routinely exploited for propaganda purposes during periods of tension and war.)

Given this history, we need to understand the strategic and economic aspects of the United States’ seemingly inexplicable turnaround on Iraq since 1990.

The Torment of Iraq

The Iran-Iraq war formally ended in 1990 with both participants—potentially prosperous and powerful countries—having suffered terrible losses. The “war of the cities” had targeted major population centers and industrial sites on both sides, particularly oil refineries. Iran, lacking the steady flow of sophisticated weapons and American help enjoyed by Iraq, had managed to fight back Iraq’s attacks by mobilizing great “human waves” of young volunteers, even teenage boys. While the tactic worked, the cost in lives was enormous. It was the fear of an internal uprising that led the Iranian leaders to come to terms with Iraq after the fall of the Fao peninsula in 1988.

Iraq’s economy, too, badly needed rebuilding. Developmental programs had been neglected for the previous decade. Exploration and development of the country’s fabulous oil resources had stagnated. To pay for the war, the country had accumulated an $80 billion foreign debt—more than half of that owed to the Gulf states. Having nothing to show for the terrible price of the war, Iraq’s rulers were desperate.

An Opportunity for the United States

For the United States, however, this catastrophe for the two countries was a satisfactory situation, and held promise of much greater gains. The exhausted Iran was no longer a major threat to American interests in the rest of the region. And, as we shall see, Iraq’s unstable situation was creating conditions for the United States to achieve a vital objective: permanent installation of its military in West Asia.Direct control over West Asian oil resources—the world’s richest and most cheaply accessible—would allow the United States to manipulate oil supplies and prices according to its strategic interests, and thereby consolidate American global supremacy against any future challenger.

The world situation was favorable to such a plan. The Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, and would be unable to prevent American intervention in the region. Nor would European, Japanese, or Chinese reservations be of much consequence. The real hurdle was the opposition of the Arab masses to any such presence of American troops—even more to their permanent installation.

What was required, then, was a credible pretext for U.S. intervention and continuing presence.

Shock to Iraq

After the close U.S.–Iraq collaboration during the 1980–1990 Iran-Iraq war described above, it is hardly surprising that Saddam Hussein expected some sort of compensation from the West for his war with Iran, and felt confident that his demands would be given a sympathetic hearing. Given that the war was projected by the West and the Gulf states (Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia) to be a defensive action against Iran’s overrunning the entire region, Saddam assumed not only that Iraq’s debt to the Gulf states would be forgiven, but indeed that those states would help with the desperately needed reconstruction of the Iraqi economy.

Instead the opposite occurred. U.S. client regimes such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates began hiking their production of oil, thus prolonging the collapse in oil prices that began in 1986. This had a devastating impact on war-torn Iraq. Oil constituted half of Iraq’s GDP and the bulk of government revenues, so a collapse in oil prices was catastrophic for the Iraqi economy. It would also curb Iraq’s rearming.

A further, remarkable development was Kuwait’s theft of oil from Rumaila field by slant-drilling (drilling at an angle, instead of straight down) near the border. (The Rumaila field lies almost entirely inside Iraq.) Given that Kuwait is itself oil-rich, the theft of Iraq’s oil appears a deliberate provocation. It is worth keeping in mind that not only did Iraq have specific border disputes with Kuwait but had also, from time to time, advanced a claim to the whole of Kuwait. In this light it is difficult to imagine that small, lightly armed Kuwait would have carried out such provocative acts as slant-drilling the territory of well-armed Iraq without a go-ahead from the United States.

Saddam’s Plea

It appears that Saddam believed he could threaten invasion of, or actually invade, Kuwait as a bargaining chip to achieve his demands—in particular the forgiveness of loans and a curb on the Gulf states’ oil production. The transcript of Saddam’s conversation with the United States ambassador to Baghdad, April Glaspie, just a week before the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, reveals much about the relationship between the two states. Saddam does not emerge as a megalomaniac, nor does he stress Iraq’s historical and legal claims to Kuwait. Rather, he emphasizes his financial needs. He pleads for American understanding by pointing explicitly to Iraq’s services to the United States and its client states in the region:

The decision to establish relations with the U.S. [was] taken in 1980 during the two months prior to the war between us and Iran. When the war started, and to avoid misinterpretation, we postponed the establishment of relations hoping that the war would end soon. But because the war lasted for a long time, and to emphasize the fact that we are a nonaligned country [i.e., not part of the Soviet bloc], it was important to reestablish relations with the United States. And we choose to do this in 1984….When relations were reestablished we hoped for a better understanding and for better cooperation….We dealt with each other during the war and we had dealings on various levels….

Iraq came out of the war burdened with $40 billion debts, excluding the aid given by Arab states, some of whom consider that too to be a debt, although they knew—and you knew too—that without Iraq they would not have had these sums and the future of the region would have been entirely different. We began to face the policy of the drop in the price of oil….The price at one stage had dropped to $12 a barrel and a reduction in the modest Iraqi budget of $6 billion to $7 billion is a disaster….

We had hoped that soon the American authorities would make the correct decision regarding their relations with Iraq….But when planned and deliberate policy forces the price of oil down without good commercial reasons, then that means another war against Iraq. Because military war kills people by bleeding them, and economic war kills their humanity by depriving them of their chance to have a good standard of living….Kuwait and the U.A.E. were at the front of this policy aimed at lowering Iraq’s position and depriving its people of higher economic standards. And you know that our relations with the Emirates and Kuwait had been good….

I have read the American statements speaking of friends in the area. Of course, it is the right of everyone to choose their friends. We can have no objections. But you know you are not the ones who protected your friends during the war with Iran. I assure you, had the Iranians overrun the region, the American troops would not have stopped them, except by the use of nuclear weapons….Yours is a society which cannot accept 10,000 dead in one battle. You know that Iran agreed to the cease-fire not because the United States had bombed one of the oil platforms after the liberation of the Fao. Is this Iraq’s reward for its role in securing the stability of the region and for protecting it from an unknown flood?…

It is not reasonable to ask our people to bleed rivers of blood for eight years then to tell them, “Now you have to accept aggression from Kuwait, the U.A.E., or from the U.S. or from Israel.”…We do not place America among the enemies. We place it where we want our friends to be and we try to be friends. But repeated American statements last year make it apparent that America did not regard us as friends (New York Times International, September 23, 1990).

Calculated Response

Without the fact of America’s intentions mentioned earlier, Glaspie’s response to Saddam’s statements would be puzzling. The conversation took place even as Iraq had massed troops at the Kuwaiti border and declared that it considered Kuwait’s acts to be aggression: it was plain to the world that Iraq was about to invade. Given the later American response, one would have expected that, a week before the invasion, the United States would send a clear message that its response to an invasion would be military intervention. Instead, the United States ambassador responded in the mildest possible terms (“concern”), emphasizing that:

We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. I was in the American Embassy in Kuwait during the late ’60s. The instruction we had during this period was that we should express no opinion on this issue and that the issue is not associated with America. James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasize this instruction.

We hope you can solve this problem using any suitable methods via Klibi or via President Mubarak. All that we hope is that these issues are solved quickly. With regard to all of this, can I ask you to see how the issue appears to us? My assessment after 25 years’ service in this area is that your objective must have strong backing from your Arab brothers. I now speak of oil. But you, Mr. President, have fought through a horrific and painful war. Frankly, we can see only that you have deployed massive troops in the south. Normally that would not be any of our business. But when this happens in the context of what you said on your national day, then when we read the details in the two letters of the Foreign Minister, then when we see the Iraqi point of view that the measures taken by the U.A.E. and Kuwait is, in the final analysis, parallel to military aggression against Iraq, then it would be reasonable for me to be concerned. And for this reason, I received an instruction to ask you, in the spirit of friendship—not in the spirit of confrontation—regarding your intentions (Ibid.; emphasis added).

This clearly indicated that while the United States would show “concern” at any invasion, it would maintain a distance and treat the matter as a dispute between Arab states, to be resolved by negotiation. Thus Saddam badly misread America’s real intentions. His invasion of Kuwait, a sovereign state and a member of the UN, provided the United States with the opportunity swiftly to mobilize the UN Security Council and form a worldwide coalition against Iraq. Crucially, his invasion of an Arab state created a situation where a number of other Arab states, such as Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia could join the coalition.

Peaceful Withdrawal a ‘Nightmare Scenario’

UN Security Council Resolution 661, passed in August 1990, demanded immediate and unconditional withdrawal from Kuwait, and imposed sanctions on Iraq. Sanctions were tried only for as long as it took for the United States to build up enough troops in the region and secure international financing for the war effort. In November 1990, the United States got UN Security Council Resolution 678 passed, providing for the use of “all necessary means” to end the occupation of Kuwait. The United States scotched all diplomatic efforts by the USSR, Europe, and Arab countries by continuing to insist that Iraq withdraw unconditionally.

A last-minute proposal was made by the French that Iraq would withdraw if the United States agreed to convene an international conference on peace in the region (this would include discussion of the continued illegal occupation by Israel of the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights, the subject of the unenforced UN Security Council Resolution 242, as well as Israel’s occupation at the time of south Lebanon). However, this too was shot down by the United States and Britain. In December 1990, the press tellingly quoted U.S. officials saying that a peaceful Iraqi withdrawal was a “nightmare scenario.”

‘Fish in a Barrel’

The colossal scale and merciless tactics of the 1991 assault on Iraq suggest that U.S. war aims greatly exceeded the UN-endorsed mission of expelling Saddam from Kuwait. The military power arrayed and employed by the United States, Britain, and their allies was grotesquely disproportionate to Iraqi defenses. Evidently, the intent was to punish Iraq so severely as to create an unforgettable object lesson for any nation contemplating defiance of U.S. wishes. The Gulf war’s aerial bombing campaign was the most savage since Vietnam. During forty-three days of war, the United States flew 109,876 sorties and dropped 84,200 tons of bombs. Average monthly tonnage of ordnance used nearly equaled that of the Second World War, but the resulting destruction was far more efficient due to better technology and the feebleness of Iraq’s antiaircraft defenses.

While war raged, the United States military carefully managed press briefings in order to suggest that the bombing raids were surgical strikes against purely military targets, made possible by a new generation of precision-guided “smart weapons.” The reality was far different. Ninety-three percent of munitions used by the allies consisted of unguided “dumb” bombs, dropped primarily by Vietnam-era B-52 carpet bombers. About 70 percent of bombs and missiles missed their targets, frequently destroying private homes and killing civilians. The United States also made devastating use of antipersonnel weapons, including fuel-air explosives and 15,000-pound “daisy-cutter” bombs (conventional explosives capable of causing destruction equivalent to a nuclear attack—also used by the United States in Afghanistan); the petroleum-based incendiary napalm (which was used to incinerate entrenched Iraqi soldiers); and 61,000 cluster bombs which dispersed 20 million “bomblets,” which continue to kill Iraqis to this day. Predictably, this style of warfare resulted in massive civilian casualties. In one well- remembered incident, as many as four hundred men, women, and children were killed at one blow when, in apparent indifference to the Geneva Conventions, the United States targeted a civilian air raid shelter in the Ameriyya district of western Baghdad. Thousands died in similar fashion due to daylight raids in heavily populated residential areas and business districts throughout the country. According to a UN estimate, as many as 15,000 civilians died as a direct result of allied bombing.

Meanwhile, between 100,000 and 200,000 Iraqi soldiers lost their lives in what can literally be described as massive overkill. The heaviest toll appears to have been inflicted by U.S. carpet bombing of Iraqi positions near the Kuwait-Iraq border, where tens of thousands of ill-fed, ill-equipped conscripts were helplessly pinned down in trenches. Most were desperate to surrender as the ground war began, but advancing allied forces had little use for prisoners. Thousands were buried alive as tanks equipped with plows and bulldozers smashed through earthwork defenses and rolled over foxholes.

Others were cut down ruthlessly as they tried to surrender or flee. “It’s like someone turned on the kitchen light late at night, and the cockroaches started scurrying. We finally got them out where we can find them and kill them,” remarked Air Force Colonel Dick “Snake” White. According to John Balzar of the Los Angeles Times, infrared films of the United States assault suggested “sheep, flushed from a pen—Iraqi infantry soldiers bewildered and terrified, jarred from sleep and fleeing their bunkers under a hell storm of fire. One by one they were cut down by attackers they couldn’t see or understand. Some were literally blown to bits by bursts of 30mm exploding cannon shells.”

Since resistance was futile and surrender potentially fatal, Iraqi soldiers deserted whenever possible. By February 26, Saddam acknowledged the inevitable and ordered his troops to withdraw from Kuwait. Surviving soldiers commandeered vehicles of every description and fled homeward.

Although an overwhelming victory already been achieved, U.S. and British forces staged a merciless attack on the retreating and defenseless Iraqi troops. The resulting massacre, immediately dubbed the “Turkey Shoot” by U.S. soldiers, took place along a sixty-mile stretch of highway leading from Kuwait to Basra, where U.S. planes cut off the long convoys at either end and proceeded to strafe and firebomb the trapped vehicles. Many thousands, including untold numbers of civilian refugees, were blown apart or incinerated. “It was like shooting fish in a barrel,” said one U.S. pilot.

Behind the Systematic Destruction of Iraq’s Civilian Infrastructure

The bombing of Iraq began on January 16, 1991. Far from restricting themselves to evicting Iraq from Kuwait, or attacking only military targets, the U.S.-led coalition’s bombing campaign systematically destroyed Iraq’s civilian infrastructure, including electricity generation, communication, water and sanitation facilities. For more than a month the bombing of Iraq continued without any attempt to send in troops for the purported purpose of Operation Desert Storm; namely, to evict Iraqi troops from Kuwait.

That the United States was quite clear about the consequences of such a bombing campaign is evident from intelligence documents now being declassified. “Iraq Water Treatment Vulnerabilities,” dated 22 January 1991 (a week after the war began) provides the rationale for the attack on Iraq’s water supply treatment capabilities: “Iraq depends on importing specialized equipment and some chemicals to purify its water supply…. With no domestic sources of either water treatment replacement parts or some essential chemicals, Iraq will continue attempts to circumvent United Nations sanctions to import these vital commodities. Failing to secure supplies will result in a shortage of pure drinking water for much of the population. This could lead to increased incidences, if not epidemics, of disease.” Imports of chlorine, the document notes, had been placed under embargo, and “recent reports indicate that the chlorine supply is critically low.” A “loss of water treatment capability” was already in evidence, and though there was no danger of a “precipitous halt” it would probably take six months or more for the system to be “fully degraded.”

Even more explicitly, the United States Defense Intelligence Agency wrote a month later: “Conditions are favorable for communicable disease outbreaks, particularly in major urban areas affected by coalition bombing….Current public health problems are attributable to the reduction of normal preventive medicine, waste disposal, water purification/distribution, electricity, and decreased ability to control disease outbreaks. Any urban area in Iraq that has received infrastructure damage will have similar problems.”

In the south of Iraq, the United States fired more than one million rounds (more than 340 tons in all) of munitions tipped with radioactive uranium. This later resulted in a major increase in health problems such as cancer and deformities. While the United States has not admitted any linkage between its use of depleted uranium (DU) shells and such health problems, European governments, investigating complaints from their veterans in the NATO attack on Yugoslavia, have confirmed widespread radiation contamination in Kosovo as a result of the use of DU shells there.

Manipulation to Justify Partial Occupation

During the conflict, the United States decided not to march to Baghdad, and decided instead to stop on the outskirts of Basra and Nasriyya. Evidently, the United States hoped that the defeat would result in Saddam being replaced in a coup by a pro-U.S. strongman from the same ruling circles. (The stability of such a regime would require the preservation of Saddam’s elite military force, the Republican Guard, which was massed in defensive positions outside Baghdad at war’s end.) The United States was uncertain of the political forces that would be unleashed in any other scenario. For example, the United States feared southern Iraq, predominantly Shiite, would come under Iranian influence if it seceded. Formal independence for Kurdish regions in the north of Iraq would destabilize the northern neighbor, the important U.S. client state Turkey, which brutally suppresses the demand of its large Kurdish population for independence.

While George Bush Sr., then president, instigated a rebellion in southern Iraq with his calls to the people to “take matters into their own hands,” when the rising actually took place, the massive U.S. occupying force still stationed in the region remained a mute spectator to its suppression. Similarly, when Iraqi forces chased Kurdish rebels in the north to the Turkish border, Turkey prevented their entry.

American complicity in these two developments was designed so that the events could be cynically manipulated by the United States to justify a permanent infringement of Iraq’s sovereignty. The UN Security Council Resolution 688 of April 1991 demanded Iraq “cease this repression” of its minorities, but did not call for its enforcement by military action. The United States and Britain nevertheless used UNSC 688 to justify the enforcement of what it called “no-fly zones,” whereby Iraqi planes are not allowed to fly over the north and south of the country (north of the 36th parallel, and south of the 32nd parallel). These zones are enforced by U.S.-U.K. patrols and almost daily bombings. After the withdrawal of UN weapons inspectors in 1998, the average monthly release of bombs rose dramatically from .025 tons to five tons. U.S. and U.K. planes could now target any part of what the United States considered the Iraqi air defense system. Between 1991 and 2000 U.S. and U.K. fighter planes flew more than 280,000 sorties. UN officials have documented that these bombings routinely hit civilians and essential civilian infrastructure, as well as livestock.

Sanctions: Genocide

After the war, Iraq remained under the comprehensive regime of sanctions placed by the UN in 1990. These sanctions were to last until Iraq fulfilled UNSC 687—elimination of its programs for developing chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, dismantling of its long-range missiles, a system of inspections to verify compliance, acceptance of a UN-demarcated Iraq-Kuwait border, payment of war compensation, and the return of Kuwaiti property and prisoners of war. Since the verification of compliance was bound to be a drawn-out and controversy-ridden process, the sanctions could be prolonged indefinitely.

The result has been catastrophic—the greatest among the catastrophes of that decade of great economic catastrophes worldwide. By 1993, the Iraqi economy, under the crunch of sanctions, shrank to one-fifth of its size in 1979, and shrank further in 1994. Rations lasted only about one-third to half of a month.

Although “humanitarian goods” were excluded from the embargo, the embargo had not clearly defined such goods, which had to be cleared by the UN sanctions committee. Later, in order to deflect growing criticism of the sanctions and in order to preempt French and Russian counterproposals, the U.K. and U.S. introduced UNSC 986. By this resolution proceeds from Iraq’s oil sales would go into a UN-controlled account; and Iraq could place orders for humanitarian goods—to be scrutinized by the UN Security Council.

The United States tried to limit the definition of “humanitarian goods” to food and medicine alone, preventing the import of items needed to restore water supply, sanitation, electrical power, even medical facilities. Among the items kept out by American veto, on the grounds that they might have a military application, were chemicals, laboratory equipment, generators, communications equipment, ambulances (on the pretext that they contain communications equipment), chlorinators, and even pencils (on the pretext that they contain graphite, which has military uses). The United States and Britain placed “holds” on $5.3 billion worth of goods in early 2002 alone. Even this does not tell the full impact, since the item held back often renders imports of other parts useless.

The Economist (London), although an eager supporter of American policies toward Iraq, described conditions in the besieged country by the year 2000:

Sanctions impinge on the lives of all Iraqis every moment of the day. In Basra, Iraq’s second city, power flickers on and off, unpredictable in the hours it is available….Smoke from jerry-rigged generators and vehicles hangs over the town in a thick cloud. The tap-water causes diarrhea, but few can afford the bottled sort. Because the sewers have broken down, pools of stinking muck have leached through the surface all over town. That effluent, combined with pollution upstream, has killed most of the fish in the Shatt al-Arab river and has left the remainder unsafe to eat. The government can no longer spray for sand flies or mosquitoes, so insects have proliferated, along with the diseases they carry.

Most of the once-elaborate array of government services have vanished. The archaeological service has taken to burying painstakingly excavated ruins for want of the proper preservative chemicals. The government-maintained irrigation and drainage network has crumbled, leaving much of Iraq’s prime agricultural land either too dry or too salty to cultivate. Sheep and cattle, no longer shielded by government vaccination programs, have succumbed to pests and diseases by the hundreds of thousands. Many teachers in the state-run schools do not bother to show up for work anymore. Those who do must teach listless, malnourished children, often without the benefit of books, desks or even black-boards (Economist, April 8, 2000).

During the first three years of the oil-for-food regime, the annual ceiling placed by the UN was just $170 per Iraqi. Out of this meager sum a further $51 was deducted and diverted to the UN Compensation Commission, which any government, organization, or individual who claimed to have suffered as a result of Iraq’s attack on Kuwait could approach for compensation. (Within the remaining sum, a disproportionate amount is diverted under U.S. direction to the Kurdish north—with 13 percent of the population but 20 percent of the funds—because this region is no longer ruled by Baghdad. The cynical intention is to point to improved conditions in this favored region as proof that it is not the sanctions but Saddam that is responsible for Iraqi suffering.) Later, the UN removed the ceiling on Iraq’s oil earnings—but prevented the rehabilitation of the Iraqi oil industry, thus ensuring that in effect the ceiling remained.

In 1998, the UN carried out a nationwide survey of health and nutrition. It found that mortality rates among children under five in central and southern Iraq had doubled from the previous decade. That would suggest 500,000 excess deaths of children by 1998. Excess deaths of children continue at the rate of 5,000 a month. UNICEF estimated in 2002 that 70 percent of child deaths in Iraq result from diarrhea and acute respiratory infections. This is the result—as foretold accurately by U.S. intelligence in 1991—of the breakdown of systems to provide clean water, sanitation, and electrical power. Adults, too, particularly the elderly and other vulnerable sections, have succumbed. The overall toll, of all ages, was put at 1.2 million in a 1997 UNICEF report.

The evidence of the effect of the sanctions came from the most authoritative sources. Denis Halliday, UN humanitarian coordinator in Iraq from 1997 to 1998, resigned in protest against the operation of the sanctions, which he termed deliberate “genocide.” He was replaced by Hans von Sponeck, who resigned in 2000, on the same grounds. Jutta Burghardt, director of the UN World Food Program operation in Iraq, also resigned, saying, “I fully support what Mr. von Sponeck was saying.”

There is no room for doubt that genocide was conscious U.S. policy. On May 12, 1996, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was asked by Lesley Stahl of CBS television: “We have heard that half a million children have died. I mean, that’s more than died in Hiroshima. And, you know, is the price worth it?” Albright replied: “I think this is a very hard choice, but the price, we think the price is worth it.”

Return of Imperialist Occupation

‘Weapons Inspection’ as a Tool of Provocation, Spying, Assassination

There can also be no doubt now by that UNSCOM, the UN weapons inspections body, was made into a tool of the U.S. mission to take over Iraq. Not only did UNSCOM coordinate consistently with U.S. and Israeli intelligence on which sites to inspect, but agents of these services were placed in the inspection teams. Scott Ritter, former UN weapons inspector, writes:

I recall during my time as a chief inspector in Iraq the dozens of extremely fit “missile experts” and “logistics specialists” who frequented my inspection teams and others. Drawn from U.S. units such as Delta Force or from CIA paramilitary teams such as the Special Activities Staff, these specialists had a legitimate part to play in the difficult cat- and-mouse effort to disarm Iraq. So did the teams of British radio intercept operators I ran in Iraq from 1996 to 1998—which listened in on the conversations of Hussein’s inner circle—and the various other intelligence specialists who were part of the inspection effort. The presence of such personnel on inspection teams was, and is, viewed by the Iraqi government as an unacceptable risk to its nation’s security. As early as 1992, the Iraqis viewed the teams I led inside Iraq as a threat to the safety of their president (Los Angeles Times, June 19, 2002).

Rolf Ekeus, who led the weapons inspections mission from 1991 to 1997, revealed in a recent interview to Swedish radio that he knew what was up: “There is no doubt that the Americans wanted to influence inspections to further certain fundamental U.S. interests.” The United States pressure included attempts to “create crises in relations with Iraq, which to some extent was linked to the overall political situation—internationally but also perhaps nationally….There was an ambition to cause a crisis through pressure for, shall we say, blunt provocation, for example by inspection of the Department of Defense, which at least from an Iraqi point of view must have been provocative.” He said that the United States had wanted information about how Iraq’s security services were organized and what its conventional military capacity was. And he said he was “conscious” of the United States seeking information on where President Saddam Hussein was hiding, “which could be of interest if one were to target him personally.”

By 1997, Ekeus reported to the Security Council that 93 percent of Iraq’s major weapons capability had been destroyed. UNSCOM and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) certified that Iraq’s nuclear stocks were gone and most of its long-range systems had been destroyed. (IAEA inspectors continue to date to travel to Iraq, and report full compliance.) In 1999 a special panel of the Security Council recorded that Iraq’s main biological weapons facility (whose stocks were supplied, as mentioned earlier, by the United States) had “been destroyed and rendered harmless.” Pressure began to build, especially from Russia and France—for reasons we will mention later—for the step-by-step lifting of sanctions, or at least clarity on what action by Iraq would lead to the lifting of sanctions.

Iraq’s fulfillment of UNSC 687 was seen by the United States as a threat to its continuing plans to strip Iraq of its tattered sovereignty. Ekeus was replaced in 1997 by the Australian Richard Butler, who owed his post to American support and paid scant heed to the other members of the Security Council. After a series of confrontational attempts to inspect sites such as the defense ministry and the presidential palaces, Butler complained of noncooperation by the Iraqis and withdrew his inspectors in November and December 1998, the second time without bothering to consult the Security Council—apart from the United States. This was in preparation for Operation Desert Fox—torrential bombing by the United States and Britain throughout southern and central Iraq from December 16 to 19, 1998. Significantly, the United States and U.K. did not bother to consult the Security Council before carrying out this action.

The Big Prize

Apart from the terrible direct human impact of the sanctions, it is important to bear in mind another calculation of the United States in prolonging the sanctions until it invades: as long as the sanctions stay, foreign investment in Iraq cannot take place, nor can rehabilitation of the country’s oil industry. Sanctions are thus an important instrument for the United States to prevent other imperialist powers from getting a foothold in Iraq—recalling an earlier theme of Iraqi history.

Iraq’s oil resources are vast, surpassed only by Saudi Arabia, and as cheap to extract as Saudi oil. The country’s 115 billion barrels of proven oil reserves are matched by perhaps an equal quantity yet to be explored. “Since no geological survey has been conducted in Iraq since the 1970s, experts believe that the proven reserves underestimate the country’s actual oil wealth, which could be as large as 250 billion barrels. Three decades of political instability and war have kept Iraq from developing 55 of its 70 proven oil fields. Eight of these fields could harbor more than a billion barrels each of “easy oil” which is close to the surface and inexpensive to extract. “There is nothing like it anywhere else in the world,” says Gerald Butt, Gulf editor of the Middle East Economic Survey. “It’s the big prize.”

Iraq’s prewar production was three million barrels a day and present production capacity is put at 2.8 million barrels a day. In fact, because of deteriorating equipment, it is hard put to reach that figure, and it currently exports less than a million barrels a day. It is estimated that, with adequate investment, Iraq’s production can reach seven to eight million barrels a day within five years. That compares with Saudi Arabia’s current production of 7.1 million barrels a day, close to 10 percent of world consumption.

This expansion of Iraqi production is impossible as long as the sanctions stay in place. The UN warned in 2000 of a “major breakdown” in Iraq’s oil industry if spare parts and equipment were not forthcoming. The United States said any extra money should only be used “for short-term improvements to the Iraqi oil industry and not to make long-term repairs.” The United States Department of Energy said: “As of early January, 2002, the head of the UN Iraq program, Benon Sevan, expressed ‘grave concern’ at the volume of ‘holds’ put on contracts for oil field development, and stated the entire program was threatened with paralysis. According to Sevan, these holds amounted to nearly 2000 contracts worth about $5 billion, about 80 percent of which were ‘held’ by the United States.”

From the point of view of U.S. oil interests, then, the sanctions are a double-edged sword: even as they keep international competition temporarily at bay, they preclude the exploitation of oil reserves with an estimated value of several trillion dollars. The war against Saddam Hussein is intended, among other things, to resolve this contradiction.

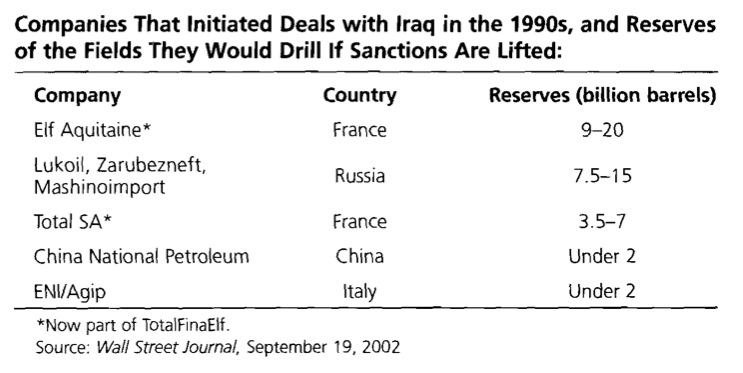

In June 2001, France and Russia proposed in the Security Council to remove restrictions on foreign investment in the Iraqi oil industry. However, the United States and U.K. predictably killed the proposal. American companies are barred by U.S. law from investing in Iraq, and so all the contracts for development of Iraqi fields have been cornered by companies from other countries. The Wall Street Journal compiled the following information from oil industry sources:

Company Country Reserves (billion barrels)

| Companies That Initiated Deals with Iraq in the 1990s, and Reserves of the Fields They Would Drill If Sanctions Are Lifted: | ||

| Elf Aquitaine* | France | 9–20 |

| Lukoil, Zarubezneft, Mashinoimport | Russia | 7.5–15 |

| Total SA* | France | 3.5–7 |

| China National Petroleum | China | Under 2 |

| ENI/Agip | Italy | Under 2 |

| *Now part of TotalFinaElf. | ||

Lukoil’s contract to drill the West Qurna field is valued at $20 billion, and Zarubezneft’s concession to develop the bin Umar field is put at up to $90 billion. The total value of Iraq’s foreign contract awards could reach $1.1 trillion, according to the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook.

One of the major objectives of the United States’ impending invasion of Iraq is to nullify these agreements. “The concern of my government,” a Russian official at the UN told the Observerin October 2002, “is that the concessions agreed upon between Baghdad and numerous enterprises will be reneged upon, and that U.S. companies will enter to take the greatest share of those existing contracts….Yes, if you could say it that way—an oil grab by Washington.”

France, too, fears “suffering economically from U.S. oil ambitions at the end of a war.” But it may nevertheless back the invasion: “Government sources say they fear—existing concessions aside—France could be cut out of the spoils if it did not support the war and show a significant military presence. If it comes to war, France is determined to be allotted a more prestigious role in the fighting than in the 1991 Gulf war, when its main role was to occupy lightly defended ground. Negotiations have been going on between the state-owned TotalFinaElf company and the United States about redistribution of oil regions between the world’s major oil companies.”

The “oil grab” was made explicit by former CIA director R. James Woolsey in an interview with the Washington Post: “France and Russia have oil companies and interests in Iraq. They should be told that if they are of assistance in moving Iraq toward decent government, we’ll do the best we can to ensure that the new government and American companies work closely with them.” But he added, “If they throw in their lot with Saddam, it will be difficult to the point of impossible to persuade the new Iraqi government to work with them.”

Ahmed Chalabi, the leader of the London-based “Iraqi National Congress,” which enjoys the tactical (and probably temporary) support of the Bush administration but virtually none in Iraq, met executives of three U.S. multinationals in October in Washington to negotiate the carving up of Iraq’s oil reserves after the U. S. invasion. Chalabi told the Washington Post: “American companies will have a big shot at Iraqi oil.” He favored the creation of a U.S.-led consortium to develop Iraq’s fields. So stark is American dominance that even Lord Browne, the head of BP (formerly known as British Petroleum) warned that “British oil companies have been squeezed out of postwar Iraq even before the first shot has been fired in any U.S.-led land invasion.”

The Logic of Invasion

Given this logic, it is hardly surprising that Bush and his cabinet were planning the invasion of Iraq even before he came to office in January 2001. The plan was drawn up by a right-wing think tank for Dick Cheney, now vice president, Donald Rumsfeld, defense secretary, Paul Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld’s deputy, Bush’s younger brother Jeb Bush, and Lewis Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff. As Neil Mackay notes, the plan shows that Bush’s cabinet intended to take military control of the Gulf region whether or not Saddam Hussein was in power:

The United States has for decades sought to play a more permanent role in Gulf regional security. While the unresolved conflict with Iraq provides the immediate justification, the need for a substantial American force presence in the Gulf transcends the issue of the regime of Saddam Hussein (“China Digs for Mid East Oil, U.S. Gets Fired Up” Reuters, September 24, 2002).

Another report prepared in April 2001 for Cheney by an institute run by James Baker (U.S. secretary of state under George Bush Sr.) ran along similar lines: “Iraq remains a destabilizing influence…in the flow of oil to international markets from the Middle East. Saddam Hussein has also demonstrated a willingness to use the oil weapon and to use his own export program to manipulate oil markets.” The report complains that Iraq “turns its taps on and off when it has felt such action was in its strategic interest to do so,” adding that there is a “possibility that Saddam Hussein may remove Iraqi oil from the market for an extended period of time” in order to damage prices. The report recommends that “therefore the United States should conduct an immediate policy review toward Iraq including military, energy, economic, and political/diplomatic assessments.” The report was an important input for the national energy plan—the “Cheney Report”—formulated by the American vice president and released by the White House in early May 2001. The Cheney Report calls for a major increase in U.S. engagement in regions such as the Persian Gulf in order to secure future petroleum supplies.

Within hours of the attacks of September 11, with no evidence pointing to Iraq’s involvement in the attacks, U.S. defense secretary Rumsfeld ordered the military to begin working on strike plans. Notes of the meeting quote Rumsfeld as saying he wanted “best info fast. Judge whether good enough to hit S.H. [meaning Saddam Hussein] at the same time. Not only UBL [the initials used to identify Usama bin Laden].” The notes quote Rumsfeld as saying. “Go massive. Sweep it all up. Things related and not.”

The Revival of Old Themes

At the start of the twenty-first century, then, broad themes of Iraqi history from the first half of the twentieth century return: imperialist invasion and occupation to grab the region’s resources, and rivalries between different imperialist powers as they strain for the prize.

Yet we ought not to forget another major theme from Iraqi history: the anti-imperialist resistance of the Iraqi masses. Even the most jaundiced Western correspondent reporting from Baghdad has been struck by how today Saddam Hussein has become, for the Iraqi people, a symbol of their defiance of American imperialism. Indeed, he has become a symbol of such defiance for the entire Arab people.

The hour of the invasion draws near. As we write this, on December 28, 2002, the Iraqi government has told a solidarity conference in Baghdad that “he who attacks our country will lose. We will fight from village to village, from city to city and from street to street in every city….Iraq’s oil, nationalized by the president…from the hands of the British and the Americans in 1972…will remain in the hands of this people and this leadership.”

The Iraqi armed forces may not be able to put up extended resistance to the onslaught. But the Iraqi people have not buckled to American dictates for the past more than eleven years of torment. They will not meekly surrender to the imminent American-led military occupation of their country. And that fact itself carries grave consequences for American imperialism’s broader designs.

as formed: 50 percent British, 25 percent German, and 25 percent Royal Dutch-Shell (Dutch- and British-owned).

The First World War (1914–1918) underlined for the imperialists the importance of control of oil for military purposes, and hence the urgency of controlling the sources of oil. As soon as war was declared with the Ottomans, Britain landed a force (composed largely of Indian soldiers) in southern Iraq, and eventually took Baghdad in 1917. It took Mosul in November 1918, in violation of the armistice with the Turks a week earlier.

During the war, the British carried on two contradictory sets of secret negotiations. The first was with Sharif Husayn of Mecca. In exchange for Arab revolt against Turkey, the British promised support for Arab independence after the war. However, the British insisted that Baghdad and Basra would be special zones of British interest where “special administrative arrangements” would be necessary to “safeguard our mutual economic interests.”

The second set of secret negotiations, in flagrant violation of the above, was between the British and the French. In the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, Iraq was carved up between the two powers, with the Mosul vilayet going to France and the other two to Britain. For its assent, czarist Russia was to be compensated with territory in northeast Turkey. When the Bolshevik revolutionaries seized power in November 1917 and published the czarist regime’s secret treaties, including the Sykes–Picot Agreement, the Arabs learned how they had been betrayed.

Iraq Under British Rule