1. Can ‘Human Nature’ Change?

Among the arguments against socialism is that it goes against human nature. “You can’t change human nature” is the frequently heard refrain. That may be true of basic human instincts such as the urge to obtain food to eat, reproduce, seek shelter, make and wear protective clothing. However, what has usually been referred to as “human nature” has changed a great deal during the long history of humankind. As social systems changed, many habits and behavioral traits also changed as people adapted to new social structures. Anatomically modern humans emerged some 150,000 to 200,000 years ago. Over the tens of thousands of years since, many different kinds of social organizations and societies have developed. Initially, most were based on hunting and gathering, while for about the last 7,000 years many have been based on agriculture. These societies were organized as clans, villages, tribes, city-states, nations, and/or empires.

Anthropologists who studied “primitive” societies found very different human relations and human nature than the highly competitive, dog-eat-dog, selfish characteristics that have dominated during the capitalist period. The economics of these early precapitalist societies often took the form of reciprocity and redistribution. Trade existed, of course, but trade between tribes was not for personal gain. Agricultural land was neither privately owned nor could it be bought and sold, instead, it was generally allocated and reallocated by village chiefs. Much of the food collected by the chiefs was redistributed at village ceremonial feasts. There were wars and domination by local tyrants—these were not perfect societies by any means—but they had different values, social mores, and “human natures.” As Karl Polanyi explained in 1944: “The outstanding discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships. He does not act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the possession of material goods; he acts so as to safeguard his social standing, his social claims, his social assets.” In such societies the economy was a function of the social relations and people were not allowed to profit from trading transactions.

The variety of structure and organization of past civilizations is truly striking. It was not so long ago—in the span of human existence—that the native peoples in North and South America had a very different consciousness than that imposed by the invasions and conquests of the European armies and settlers. Thus Christopher Columbus wrote after his first voyage to the West: “Nor have I been able to learn whether they held personal property, for it seemed to me that whatever one had, they all took shares of….They are so ingenuous and free with all they have that no one would believe it who has not seen it; of anything they possess, if it be asked of them, they never say no; on the contrary, they invite you to share it and show as much love as if their hearts went with it.”

According to William Brandon, a prominent historian of American Indians: “Many travelers in the heart of America, the Indian world real before their eyes, echoed such sentiments year after year, generation after generation. These include observers of the most responsible sort, the missionary Du Tertre for a random example, writing from the Caribbean in the 1650s: ‘…they are all equal, without anyone recognizing any sort of superiority or any sort of servitude….Neither is richer or poorer than his companion and all unanimously limit their desires to that which is useful and precisely necessary, and are contemptuous of all other things, superfluous things, as not being worthy to be possessed….’” And Montaigne wrote of three Indians who were in France in the late sixteenth century. They explained to him about the common Indian custom of dividing the people into halves, groups with special and separate duties for ritual or administrative reasons, such as the Summer and Winter people of the various North American tribes. The Indians were struck by the two opposing groups in France. “They had perceived there were men amongst us full gorged with all sorts of commodities and others which hunger-starved, and bare with need and povertie begged at their gates: and found it strange these moieties so needy could endure such an injustice, and they tooke not the others by the throte, or set fire on their house….”1

The European settlers in the thirteen colonies in what became the United States had no doubts about their superiority in every way over the “wild savage” Indians. But let us take a look at the Iroquois Nations. They had democracy involving not political parties but people’s participation in decision-making and in removing unsatisfactory officials. Women voted with the men and had special responsibilities in certain areas. At the same time the “civilized” settlers relied on white indentured servants and black slaves and severely constrained women’s rights. It took three and a half centuries after the pilgrims landed to free the slaves and four centuries for women to get the right to vote!

We have briefly referred above to societies in which economics was subservient to social relations. That changed dramatically in the evolution of capitalism as private property, money, and trade for gain came to the forefront. Social relations became but reflections of the dominating force of society’s capitalist economics instead of the reverse. Aristotle foresaw the dangers ahead because some aspects of what would become capitalism were present in the ancient world:

There are two sorts of wealth-getting, as I have said; one is a part of household management, the other is retail trade: the former necessary and honorable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another. The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. (Politics)

Although Aristotle supported slavery, which he apparently found natural, he thought selling and charging interest to make a gain unnatural. The situation is now reversed. Most people nowadays see slavery as unnatural, while selling to make a profit and charging interest seem like the most natural of human activities.

It is, of course, doubtful whether the concept of a “human nature” means anything at all because the consciousness, behavior, habits, and values of humans can be so variable and are influenced by the history and culture that develops in a given society. Not only has so-called human nature changed, but the ideology surrounding the components of human nature has also changed dramatically. The glorification of making money, the sanctioning of all the actions necessary to do so, and the promotion of the needed human traits—“unnatural” and repugnant to Aristotle—is now the norm of capitalist societies.

During capitalist development, including the recent past, what many have considered obvious characteristics of human nature have been shown to be nonsense. For example, it was once considered a part of human nature that women were not able to perform certain tasks competently. It was extremely unusual for women to be physicians, partially because of the belief that they were not capable of learning and using the needed skills. Now women doctors are common, and women are frequently more than half of the students in medical school. The recent harebrained remarks by Harvard University’s president that perhaps it is part of human nature that women can’t do quality work in math and science indicates that a strong ideological view of human nature still exists. This sentiment is now supposedly made more scientific by presumed genetic differences, even in areas where none have been demonstrated. It is clear what many consider human nature is actually a set of viewpoints and prejudices that flow out of the culture of a particular society.

Capitalism has existed for about 500 years—mercantile (or merchant) capitalism for about 250 followed by industrial capitalism for the last 250—less than 0.4 percent of the entire period of human existence. (In large parts of the world, capitalism arrived later as the system expanded and has held sway for an even smaller portion of time.) During this small slice of human history the cooperative, caring, and sharing nature within the human character has been downplayed while aggressive competitiveness has been brought to prominence for the purpose of fostering, and surviving within, a system based on the accumulation of capital. A culture has developed along with capitalism—epitomized by greed, individualism (everyone for themselves), exploitation of men and women by others, and competition. The competition occurs among departments in companies and, of course, among companies and countries, and workers seeking jobs, and it permeates people’s thinking. Another aspect of the culture of capitalism is the development of consumerism—the compulsion to purchase more and more, unrelated to basic human needs or happiness. As Joseph Schumpeter described it decades ago “…the great majority of changes in commodities consumed has been forced by producers on consumers who, more often than not, have resisted the change and have had to be educated by elaborate psychotechnics of advertising” (Business Cycles, vol. 2 [McGraw-Hill, 1936], 73).

If human nature, values, and relations have changed before, it hardly needs pointing out that they may change again. Indeed, the notion that human nature is frozen into place is simply another way that those supporting the present system attempt to argue that society is frozen in place. As John Dewey wrote in an article on “Human Nature” for The Encyclopeia of the Social Sciences in 1932,

The present controversies between those who assert the essential fixity of human nature and those who believe in a great measure of modifiability center chiefly around the future of war and the future of a competitive economic system motivated by private profit. It is justifiable to say without dogmatism that both anthropology and history give support to those who wish to change these institutions. It is demonstrable that many of the obstacles to change which have been attributed to human nature are in fact due to the inertia of institutions and to the voluntary desire of powerful classes to maintain the existing status.

2. Why Not Capitalism?

The case against capitalism contains a number of facets. First, capitalism is a system that must expand—leading to colonial and imperial wars and economic domination of poorer countries. The basic working of the system creates great wealth and poverty simultaneously at national and international levels. A consequence of this is that a large part of humanity is doomed to a subservient position, with many living precarious and wretched lives. Capitalism also tends to wreak ecological havoc as it develops and grows because there is no other systemic goal than the pursuit of capital accumulation—its prime moving force. It tends to use up natural resources, both renewable and nonrenewable, without regard to their limited nature. And while the worst effects of capitalism can sometimes be mitigated, reforms can be undone when capitalists view them as barriers to capital accumulation and have the power to legislate the return to more unfettered conditions.

A. Inherent Expansionism of Capitalism

Trade for monetary gain and the extraction of precious metals became the dominant motive forces at the center of society in the emerging mercantile capitalism, resulting in wealth accumulation by merchants and bankers in the powerful countries. This led to struggles between social groups and wars between nations searching for more power, property, and wealth. However, the oceans set limits on European trade with other parts of the world because it was essentially confined to land routes until the late fifteenth century. The exploration of the oceans by European nations that began at this time was made possible by the development of powerful artillery, new navigational instruments, and large sailing ships that could hold significant numbers of both soldiers and cannon. “The Europeans rapidly improved upon [military technology, naval artillery, and sailing ships] before the non-Europeans were able to absorb [them]. The disequilibrium grew, therefore, progressively larger” (C. M. Cippola, Guns and Sails in the Early Phase of European Expansion 1400–1700 [Collins, 1965]).

The initial motivation for the European explorations and conquests abroad was usually mercantile trade for high value products such as spices and precious minerals. It took only a few decades for the European nations to become the predominant masters of the oceans and gain entry or access to many nations around the world. They began to establish small enclaves, some of which they were able greatly to expand because of the decimation of native populations following the introduction of Eurasian germs to which there was little resistance among the people of the conquered lands. Although the push abroad started in the late fifteenth century, for the sake of convenience, 1500 is generally used to mark the start of the era of merchant capitalism. Merchant capitalism created a world market, a massive concentration of wealth (largely based on general trade as well as gold and silver stolen from the Americas), and the beginning of colonization that affected huge segments of the overseas world. Indigenous people were wiped out by war, enslavement, and disease or were otherwise marginalized. European markets with Africa concentrated for centuries on the slave trade, which predominantly benefited Britain.

Merchant capitalism created the beginnings of a world market and helped provide the accumulated wealth that gave birth to the industrial revolution of mid-eighteenth century. Thus, about two and a half centuries ago a new type of society developed in Europe—industrial capitalism—and has since spread to essentially all corners of the world. Built into the very fabric of modern, or industrial, capitalism is the need to expand control and influence to foreign shores—imperialism. There are a number of significant forces that led to the drive to expand and during various periods one or another may have been predominant. However, they are generally inseparable, because they are all derived from the workings of capitalism.

Control over foreign natural resources (in competition with other capitalists and/or other nations) is needed to obtain secure sources of essential materials for production—from cotton to bauxite to oil to copper and so on. The U.S. war on Iraq and the attempt to influence the politics and economy of that country and region are incomprehensible without viewing it as part of a strategy to control Middle Eastern oil, which amounts to 65 percent of the world’s known reserves. The United States currently imports over half its oil needs, 100 percent of its needs for seventeen minerals, and relies heavily on imports for many more.

The push continually to invest profits in order to accumulate more and more capital—the driving force of industrial capitalism—and production stimulated by competition among firms for market share led capitalists to develop new products and expand their markets internally. Once internal markets are saturated or close to saturation capitalists search abroad for profitable opportunities to overcome the stagnation that begins to develop. The persistent excess of investment and production relative to effective demand, the cause of capitalism’s tendency toward stagnation, was identified by Marx as a characteristic of the system.

If this new accumulation meets with difficulties in its employment, through a lack of spheres of investment, i.e. due to a surplus in the branches of production and an oversupply of loan capital, this plethora of loanable money capital merely shows the limitations of capitalist production…an obstacle is indeed immanent in its laws of expansion, i.e., in the limits in which capital can realize itself as capital. (Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 507)

Investing abroad also offers opportunities to take advantage of lower-cost labor and fewer environmental restrictions, allowing more profitable production for the foreign and/or home markets. Having many operations abroad offers the opportunity for firms to allocate costs and income to various international subsidiaries in ways that minimize tax obligations.

In the monopolistic stage of capitalism that arose in the twentieth century, the struggle between giant corporations for bigger shares of the markets at home and abroad was another factor contributing to the drive for expansion. Corporations frequently need external funding to feed this. Much of the surplus generated by corporations is dissipated in nonproductive ways, such as for advertising and promotion or outrageously high compensation for senior corporate officers. For example, the amount that the CEO of Wal-mart earns every two weeks is equivalent to what an average worker in that company earns in an entire lifetime (Paul Krugman, New York Times, May 13, 2005). Hence, although corporations can still generate profits for investment internally, they frequently require access to capital for expansion of production or acquisitions of other companies. In order to attract the bankers and stock market investors they need to show significant or potential growth.

Lastly, the invasion of the periphery by banks from the core capitalist countries assists foreign investment and helps foreign investors and their allies in the local ruling class transfer profits back to the core countries. Banks from the center also find it profitable to peddle loans to private and public agencies in the periphery, enhancing the development of debt peonage. Interest (plus some of the principal) equivalent to the original loan is rapidly transferred back to the center, leaving behind a long-term obligation to pay.

Creating colonial control was the way emerging capitalist centers assured power over foreign resources and markets. The expansion of the more advanced industrial and military powers led to outright control of most of the globe. By 1914, colonies of the rich and industrialized countries covered approximately 85 percent of the earth’s land surface. (And people talk nowadays about “globalization” as if it were a completely new phenomenon rather than a renewed imperialist thrust!) The World Wars of the twentieth century were fought primarily over the question of the division of the world among the great powers. Bitter struggles and wars after the Second World War forced the colonial powers to decolonize. However, after decolonization, the rich nations of the center of the capitalist world economy continued to dominate the much larger underdeveloped world. A common feature of the years of colonialism and those after the former colonies gained political independence was the economic subordination of the poor nations to the needs and wishes of capital from the center. This history of colonial and imperialist domination has distorted the economies of the periphery in ways that have inhibited self-development. The main feature of this dependency of the poorer nations—the extraction of wealth to support capital accumulation by the dominant powers—continues to this day. Following decolonization, new means were needed to oversee and continue to reproduce the dependence of the poor countries of the periphery. The IMF and World Bank now perform much of the enforcement role once played by colonial occupation and military force, but armed forces are still used to enforce imperial will.

The importance of the global penetration of capital to the success of the system as a whole has been simply stated by Joan Robinson: “few would deny that the expansion of capitalism into new territories was the mainspring of…‘the vast secular boom’ of the last two hundred years.”2 However, this expansion inherent to capitalism creates nearly perpetual warfare and subjugates the economies of the periphery to the needs of the corporations based in the system’s center. It also works to maintain a large portion of the world’s people under very harsh conditions (see below).

B. Capitalism and the Human Condition

Capitalism, with a number of political variations, has produced more goods, inventions, new ideas, and technological advances than in all of previous history. During the approximately two and a half centuries of industrial capitalism there has been—with the important exceptions of severe recessions, depressions, and wars—nearly continuous expansion of the leading capitalist countries. But what has this enormous progress and development of productive capacities created as far as the living conditions and relations of the people on this earth? On the one hand, there is a significant portion of the world’s population, perhaps 20 percent, that lives in comfort with many opportunities for education, housing, and purchasing a variety of goods almost at will. But within this generally well-off group there is a very uneven distribution of riches, with the wealthiest controlling huge amounts of wealth. The wealthiest 691 people on earth have a net worth of $2.2 trillion, equivalent to the combined annual GDP of 145 countries—more than all of Latin America and Africa combined! The richest 7.7 million people (about 0.1 percent of world’s population), with net financial worth of more than $1 million, control approximately $28.8 trillion—equivalent to 80 percent of the annual gross domestic product of all the countries of the world. This is more than the combined annual GDP of all countries of the world minus the United States. (It actually also encompasses about 40 percent of the U.S. GDP as well.)

Despite the huge quantity of wealth produced and accumulated in a few hands, the details of how so much of humanity actually lives—the numbers and conditions of the wretched of the earth—are outrageous.

Of the approximately 6.3 billion people in the world:

- About half of humanity (three billion people) are malnourished and are chronically short of calories, proteins, vitamins, and/or minerals.3 Many more are “food insecure,” not knowing where their next meal is coming from. The UN estimates that “only” 840 million (including ten million in the wealthy core industrialized countries) are undernourished, but this is greatly below most other estimates.

- One billion live in slums (about one-third of the approximately three billion people living in cities).

- About half of humanity lives on less than what two dollars a day can purchase in the United States.

- One billion have no access to clean water.

- Two billion have no electricity.

- Two and a half billion have no sanitary facilities.

- One billion children, half of the world’s total, suffer extreme deprivation because of poverty, war, and disease (including AIDS).

- Even in wealthy core capitalist countries, a significant portion of the population lives insecure lives. For example, in the United States twelve million families are considered food insecure and in four million families (with nine million people) someone regularly skips a meal so there will be enough food for other family members.4

Another part of the human condition over the past two and a half centuries of industrial capitalism has been the almost continuous warfare with hundreds of millions of people killed. Occupation, slavery, genocide, wars, and exploitation are part of the continuing history of capitalism. Wars have resulted from capitalist countries fighting among themselves for dominance and access to global markets, from attempts to subjugate colonies or neocolonies, and ethnic or religious differences among people—many of which have been exacerbated by colonial occupation and/or imperial interference. The basic driving force of capitalism, to accumulate capital, compels capitalist countries to penetrate foreign markets and expand their market share. However, it is impossible to separate the leading imperialist countries’ economic drive to invest and sell abroad from their political and military policies—all interests are intertwined in a very dangerous combination. Warfare is continuing in the post-Cold War era—with the United States eager to display its military power—and there is potential for even more misery. The estimate that 100,000 Iraqis have died as a result of the U.S. invasion gives some idea of the magnitude of the disaster that has fallen on that nation.

C. The Connection Between Wealth and Poverty

There is a logical connection between capitalism’s achievements and its failures. The poverty and misery of a large mass of the world’s people is not an accident, some inadvertent byproduct of the system, one that can be eliminated with a little tinkering here or there. The fabulous accumulation of wealth—as a direct consequence of the way capitalism works nationally and internationally—has simultaneously produced persistent hunger, malnutrition, health problems, lack of water, lack of sanitation, and general misery for a large portion of the people of the world.

The difficult situation of so much of humanity partly occurs because the economic system does not produce full employment. Instead, capitalism develops and maintains what Marx called the reserve army of labor—a large sector of the population that lives precariously, sometimes working, sometimes not. These workers might be needed seasonally, at irregular times, when there is a temporary economic boom, for the military, or not at all. In the wealthy countries, members of the reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed are generally the poorest, living under difficult conditions including homelessness. Their very existence maintains a downward pressure on wages for the lower echelons of workers. (For a full discussion, see Fred Magdoff & Harry Magdoff, “Disposable Workers,” Monthly Review, April 2004.)

In the countries of capitalism’s periphery there are several factors at work that maintain such large numbers of people in miserable circumstances. Part of the story is the wealth extracted from the countries of the periphery when repatriated profits exceed new investments and natural resources are exploited for the wealthy core countries. Also, banks push loans on countries resulting in even more extraction of wealth from the periphery through a system of debt peonage. More and more, the people of the periphery serve as participants in the reserve army of labor for capital from abroad as well as for their own capitalists. The labor forces of many former colonies were created purposefully by breaking up their societies and their way of living. One way this was accomplished was to require that a tax be paid, compelling people to join the money economy. The change from traditional land tenure patterns to one based on private ownership was another way colonial powers undermined the conditions of peasant communities. And as many people are pushed from the land and into urban slums in the periphery, there are not sufficient jobs to absorb the workers, creating a huge humanitarian crisis.5 Additionally, the power that goes along with wealth allows the manipulation of the political and legal system to benefit continued accumulation at the expense of the sharing or redistribution that might have occurred in more “primitive” societies.

The wealth of the rich countries at the center of the capitalist system depends heavily to this day on the extraction of resources and riches from the periphery. The leading global capitalist investors are in the wealthy industrial countries, but their accumulation is based on the exploitation of the entire world: Accumulation on a World Scale is the way Samir Amin described this in the title of his famous book. Instead of allowing the countries of the periphery to use their economic surplus to advance their own internal interests, the center countries invest part of this surplus to penetrate the rest of the world, actively assisted in this process by the home country’s political establishment and U.S. (or NATO) military force. This means that poor countries are not able to use their potential economic surplus to meet their societal needs; instead it flows into the coffers of the ruling classes in the rich countries and partly into luxury goods for their own small, wealthy comprador elites that are complicit with the interests of foreign capital.

In the early years of industrial capitalism, accumulation of capital from the periphery mainly took the form of outright robbery of precious metals, followed by agricultural products produced by slave labor, the supply of which was itself a profitable business. Later, loans and investments resulted in the extraction of profits in the form of hard currency—creating a perpetual debt crisis for many countries—while natural resources such as oil and bauxite were also extracted. In the early phase of capitalism the “mother countries” of the center did everything possible to destroy businesses in the periphery that might compete with those at home. Thus, the forcible British destruction of India’s textile industry so that Indians would be compelled to purchase goods produced in England.

During the early years of capitalism the core countries worked energetically to protect their industries and other businesses from competition from abroad. Now, the great strength of these mature businesses and their need to penetrate the periphery more efficiently has resulted in capital in the center states, their governments, and the “international” organizations working in their interests all jointly promoting “free trade”—while hypocritically still supporting many advantages for “home” industries both internally and in their dealings around the world. In the current wave of global capitalist expansion, with capital having gained a great degree of mobility, goods once produced in the countries of the center are more and more produced in countries with low wages. This serves two purposes: In addition to making it possible to undersell competitors still producing in the core, it provides an opening to new markets in the country and region in which the products are now produced, as a class with significant purchasing power develops in the countries of the periphery. Importation of low-cost manufactured goods from abroad, produced with exploited and underpaid labor, provides another way that the wealth of the core is reinforced and reproduced.

Capitalism, through a variety of mechanisms—from outright robbery and colonial domination in the early years to the imperialist relations in its more mature version—continues to reproduce the wealth of the core and the underdevelopment of the periphery. It also continues to produce and reproduce a class structure in each country—including a servile ruling class in the periphery with their foreign bank accounts and faith in U.S. military force.

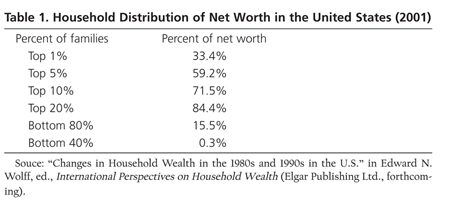

The production and continual reproduction of a class structure, with an always present reserve army of labor means that there will always be significant inequality under capitalism. Hierarchy and classes mean that differences prevail at every level and with a large overwhelming number of people with little to no effective power. The distribution of wealth in the United States indicates the extent of inequality. The bottom 80 percent of the people own less than half the wealth that is owned by the top 1 percent, and the bottom 40 percent of households own 0.3 percent of the total wealth (table 1).

Differences also persist between regions of countries and among different ethnic groups. For example, in 2002 the average family net worth of whites ($88,000) was eleven times greater than for Hispanics and fourteen times that of blacks (“Wealth gap among races widens in recession,” Associated Press, October 18, 2004). While only 13 percent of white families had zero or negative net worth, close to one-third of black and Hispanic families had no net wealth. Average family incomes of blacks and Hispanics in 2000 were approximately half that of whites. And significantly fewer black males are in the labor force than their white counterparts—67 versus 74 percent participation rates, respectively (2005 Economic Report of the President, http://www.gpoaccess.gov/eop/).

Little needs to be said about the huge difference in national wealth between the highly developed capitalist countries and those in the periphery. While the average developed country’s per capita GDP is approximately $30,000, it is around $6,000 in Latin America and the Caribbean, $4,000 in North Africa, and $2,000 in sub-Saharan Africa. But these numbers hide the worst of the problems, because per capita GDP in Haiti is $1,600, in Ethiopia it is $700, and in six countries in sub-Saharan Africa average per capita income is $600 or less. The wealthy countries with 15 percent of the world’s population produce 80 percent of its GDP. On the other hand, the poorest countries with close to 40 percent of the world’s population produce only 3 percent of its wealth.

D. Ecological Degradation

Ecological degradation occurred in numerous precapitalist societies. But with capitalism there is a new dimension to the problem, even as we have better understood the ecological harm that human activity can create. The drive for profits and capital accumulation as the overriding objective of economic activity, the control that economic interests exert over political life, and the many technologies developed in capitalist societies that allow humans rapidly to change their environment—near and wide, intentionally or not—mean that adverse effects on the environment are inevitable. Pollution of water, air, and soil are natural byproducts of production systems organized for the single goal of making profits.

Under the logic of capitalist production and exchange there is no inherent mechanism to encourage or force industry to find methods that have minimal impact on the environment. For example, new chemicals that are found useful to produce manufactured goods are routinely introduced into the environment—without the adequate assessment of whether or not they cause harm to humans or other species. The mercury given off into the air by coal-burning power plants pollutes lakes hundreds of miles away as well as the ocean. The routine misuse of antibiotics, added to feeds of animals that are being maintained in the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions of factory farms, has caused the development of antibiotic resistant strains of disease organisms. It is a technique that is inconsistent with any sound ecological approach to raising animals, but it is important to capital because profits are enhanced. In addition, the development of an automobile-centered society in the United States has had huge environmental consequences. Vast areas of suburbs, sometimes merging into a “megatropolis,” partially erase the boundaries between communities. The waste of fuel by commuting to work by car is only part of the story of suburbanization, as some people work in the city while others work in different suburbs. Shopping in malls reachable only by cars and taking children to school and play require transportation over significant distances.

Climate change resulting from global warming, not completely predictable, but with mostly negative consequences, is another repercussion of unfettered capitalist exploitation of resources. As fossil fuels are burned in large quantities by factories, electrical generation plants, and automobiles and trucks, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have increased. There is some concern that the gradual warming could actually lead to a fairly rapid change, with such factors as the melting of polar ice, changes in precipitation and river flow, and a cessation of the thermohaline conveyor (of which the Gulf Stream is a part) that brings warm water to the north Atlantic and helps keep North America and Europe warm (see “The Pentagon and Climate Change,” Monthly Review, May 2004).

An added dimension of capitalism’s threat to the environment is the deep thread in western thought that God gave the earth to humans to exploit. This notion is derived from the Bible, where the book of Genesis (1:28) contains the following:

And God blessed them [Adam and Eve], and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

A relatively recent virulent strain of anti-environmentalism exists among evangelical Protestants in the United States, maintaining that the end of the world is near. Thus, it makes no real difference what happens to our natural resources and the earth’s life support systems (see Bill Moyers, “Welcome to Doomsday” New York Review of Books 52, no. 5 [March 24, 2005]).

E. Resource Limits

A system that by its very nature must grow and expand will eventually come up against the reality of finite global natural resources. The water, air, and soil can continue to function well for the living creatures on the planet only if pollution doesn’t exceed their capacity to assimilate and render the pollutants harmless. Additionally, natural resources are used in the process of production—fuel (oil and gas), water (in industry and agriculture), trees for lumber and paper, a variety of mineral deposits such as iron ore and bauxite, and so on. Some resources such as forests and fisheries are of a finite size, but can be renewed by natural processes if used in a planned system that is flexible enough to change as conditions warrant. Future use of other resources—oil and gas, minerals, aquifers in some desert areas (prehistorically deposited water)—are limited forever to the supply that currently exists.

Capitalists generally only consider the short term in their operations—perhaps three to five years at best. This is the way they must function because of unpredictable business conditions (phases of the business cycle, competition from other corporations, prices of needed inputs, etc.) and demands from speculators looking for short-term returns. Capitalists, therefore, act without any recognition that there are natural limits to their activities—as if there is an unlimited supply of natural resources for exploitation. When each individual capitalist pursues the goal of making a profit and accumulating capital, decisions are made that collectively harm society as a whole. For example, the well-documented decline, almost to the point of extinction, of many ocean fish species is an example. It is in the short-term individual interests of the owner of a fishing boat—some of which operate at factory scale, catching, processing, and freezing fish—to maximize their take. Although there is no natural limit to human greed, there are limits to many resources, including the productivity of the seas.

The use of water for irrigation is an old practice, which only in the last fifty years has started to reach its natural limits. The capacity of some watersheds and rivers are fully exploited—so much water is withdrawn from the Yellow River in Northern China, in most years it doesn’t reach the sea. With the use of powerful pumps that can exploit the deeper aquifers and pump at higher rates, water can be withdrawn faster than it is replenished by rainfall percolating through the soil. The first people to point out that withdrawing more water than was replenished by rainfall from the Oglala Aquifer, which underlies the portion of the Great Plains from South Dakota to the panhandle of Texas, could not continue for much longer and would require deeper and deeper wells until it was impractical if not impossible to continue its use, were accused of being communists! That’s one indication of how uncapitalist it is to think about possible resource limits to economic activity.

How long it will take before nonrenewable deposits are exhausted depends upon the size of the deposit and the rate of extraction of the resource. While depletion of some resources may be hundreds of years away (assuming that the rate of growth of extraction remains the same) limits for some important ones—oil and some minerals—are not that far off. For example, it is estimated that at the rate oil is currently being used, known reserves will be exhausted within the next fifty years—the 2003 ratio of reserves to annual extraction is forty-one years, down from nearly forty-four years in 1989 (British Petroleum, Statistical Review of World Energy 2004, http://www.bp.com). Iron ore production—the basic ingredient of iron and steel products used—grew by about 16 percent from 2003 to 2004. If it grows by 7 percent annually from now on, known deposits of iron ore will be exhausted in about sixty years. If the rapid increase in use of copper continues, all known reserves will be exhausted in a little over sixty years.

In the face of limited natural resources, there is no rational way to prioritize under a capitalist system, in which the market—that is the wealthy with their market power—decides how commodities are allocated. When extraction begins to decline, as is projected for oil within the near future, price increases will put increased pressure on what had been until recently the boast of world capitalism, the supposedly middle-class workers of the center.

F. Capitalism with a Human Face? Reform and Counter-Reform

Reforms can be enacted to soften the social and ecological effects of the raw workings of the capitalist system. Certainly many have occurred, including those that resulted in workers’ gains in the core capitalist countries such as a shorter workday and week, the right to form a union, a government run social security retirement system, higher incomes, and worker safety laws. Concern over the environment has led to laws that have improved the sorry state of air and water quality in most of the advanced capitalist countries. However, as we are now seeing in the countries of the core, it is possible for capital to reverse the gains that were won through hard-fought struggles of the working class. During periods in the ebb and flow of the class struggle when conditions are decidedly in favor of capital, there will be an attempt to reverse the gains and to push towards minimal constraints and maximum flexibility for capital.

At the end of the Second World War, capital, fearing revolution that could destroy the system and needing the cooperation of labor to get the countries back on their feet, promoted a welfare state in much of Europe—paid vacations, better wages, and Germany even placed workers on corporations’ boards of directors. In the United States the welfare state began with Roosevelt’s New Deal and new programs were added through the 1960s.

Following the Second World War as the economies were rapidly rebuilding—spurred on by the stimulus of the automobile and suburbanization with all their ramifications—there was plenty of money to fund welfare programs, provide higher salaries for labor, and still make large profits. When the economy was growing rapidly taxes also increased (without much effort) to fund new programs. The concern for social stability in the 1960s and the desire to have the masses’ support in the Cold War, especially in the United States, are also part of the explanation for increases in social programs. What actually happened also depended on the militancy of unions as well as other forms of class struggle such as the black movement for political and economic rights. But with the growth of larger and larger corporations, competition between countries became more intense and there were no new forces stimulating the economy to grow rapidly, as had occurred from the end of the Second World War through the 1960s.

When economic stagnation developed in the 1970s, capital responded in a number of ways. Investment strategies changed in order to sustain profits—there was a diversion from investment to produce physical commodities toward the service sectors and the speculative world of finance (creating and selling a variety of financial products). With stagnation, capitalist societies, as throughout their history in depressions, also shifted the burdens of stagnation, militarism, and wars to the working people (and the colonial possessions). Beginning in the 1980s those at the top of society have promoted a continuous class war aimed at reducing corporate taxes and taxes on the wealthy. Also starting in the 1980s—and accelerating at this time—the vested interests of capital have unleashed a campaign to dismantle as many worker rights as possible (including those in the reserve army): attacking welfare programs, making it harder to unionize workers and easier to fire them, decreased pension coverage, privatizing basic services (including schools), and attempting to privatize social security. Conservatives in the United States never accepted government social programs and have established the goal of rolling back those initiated during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the 1960s Great Society era, returning to the situation before the national government had a major role in protecting the rights of workers. There is also a similar drive by capital in Europe to decrease worker protections and rights under the guise that it is necessary to make their industries more competitive in the world market.

The greed, individualism, and competition fostered by capitalism makes it relatively easy to justify elimination of programs that help workers and the poor. Thus, capitalism can have a “human face” for only short periods of time. Reforms that achieve modest gains can never be counted on to achieve a truly humane society. As we now see, counter-reforms will occur as the strength of capital increases relative to that of labor, and class war from above becomes the norm. But more importantly, the evils of inequality, poverty and misery, environmental degradation, using up resources faster than replacements can be found or developed—as well as the imperialist economic, political, and military penetration of the periphery by leading core countries—all flow out of the very nature of the capitalism.

A new society is needed because the evils are part of the DNA of the capitalist system. Moving away from capitalism is not really a choice—the environmental constraints and the growth of immiseration will force a change in the society. The future points to limited possibilities—a turn to fascism (barbarism) or the creation of a collective society that can provide the basic needs for all of humanity.

3. Learning from the Failures of Post-Revolutionary Societies

In view of the extent of misery and the threat of environmental disaster endemic to capitalism, what needs to be done? A simple, direct answer was recently given by Nora Castoneda, founder of a bank for women in Venezuela: “We are creating an economy at the service of human beings instead of human beings at the service of the economy.” This description can stand as the essence of the socialist goal. It may well represent the hopes of billions of people. However, developments of the two great socialist revolutions—in the soviet Union and China—have left many people on the left disheartened and discouraged about the prospects of socialism.

Unfortunately, many of us have a simplified view of history and overlook the contradictions on the road to a new social order. The post-revolutionary societies accomplished a great deal: full employment, mass education, medical service for all the people, industrialization, longer life spans, sharp declines of infant mortality, and much more. They marked advances on the road to socialism. But after a relatively short period they each took detours to social systems that were neither capitalist nor socialist. Eventually, both became firmly established on the road to capitalism. But how did these revolutions become sidetracked, and are there lessons to be learned for new attempts to take the radical road, the socialist road? Hard answers are difficult to come by and we don’t pretend to know all the answers. But we would like to note lines of study and analysis that might help understand the failures.

Most important, in our opinion, is that departures from the socialist road were not inevitable; rather they are outgrowths of specific historical circumstances—and to a large extent the endurance of old social groups and old ways of thinking. Capitalist ideology persisted and served new ruling groups, many of whom, in pursuing their self-interest, played the game of grabbing a higher rung in the hierarchy while holding on to the morality of the old overthrown ruling class. The professed goal of true democracy—people’s intense involvement in determining and participating in setting policy and practice in the new society—was more talk than action.

Perhaps one, if not the leading, lesson of the post-revolutionary societies is the affirmation that socialism cannot arrive overnight—the road to such a major transformation of social structure and people’s consciousness is indeed very long. It is also full of pitfalls. Mao put it simply and clearly:

Marxism-Leninism and the practice of the Soviet Union, China and other socialist countries all teach us that socialist society covers a very, very long historical stage. Throughout this stage, the class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat goes on and the question of “who will win” between the roads of capitalism and socialism remains, as does the danger of restoration of capitalism. (Mao Zedong, “On Khrushchev’s Phony Communism and Its Historical Lessons for the World: Comment on the Open Letter of the Central Committee of the CPSU,” 1964)

The long transition to fully-developed socialism requires a truly new culture imbued with a new ideology. A fundamental reversal of the dominant mentality of capitalist times is crucial for the creation of a new social order. But ideology, values, ethics, and prevailing beliefs in capitalism are strong and cannot evolve overnight to something different. We live in a society that promotes and often requires selfishness, greed, individualism, and a dog-eat-dog competitive spirit. A socialist society, on the other hand, would require and help produce a collective ideology adapted to a totally different social practice—one focused on serving all the people, outlawing hierarchy, overcoming differences in status, and moving toward egalitarianism. Marx posed the difficult question about such changes in philosophical terms:

The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men are products of changed circumstances and upbringing, forgets that it is men who change circumstances and that the educator must himself be educated. Hence this doctrine is bound to divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society. The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-change [Selbstveränderung] can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice. (Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach) [Note that “man” was not the word Marx used. He wrote “Mensch” which in German means “person” and applies equally to men and women.]

The crucial phrase used in the above quotation is “revolutionary practice.” That calls for a high degree of people’s involvement in the revolutionary process of building a new society. And that, at the very least, requires and should encourage the people’s full freedom to criticize leaders and dispute policies.

A. The Experience of the Soviet Union

Many factors underlie the failure to establish a socialist society in the Soviet Union. Despite major improvements in social welfare and an impressive industrialization, a clear road to socialism was never firmly established—certainly not the socialism Marx advocated. While not capitalist, neither was the Soviet Union socialist. We have previously discussed in these pages in some detail our understanding of the economic and social problems that developed in the Soviet Union.6 We will not repeat all of the arguments and discussion, but rather give a brief summary of key issues, occasionally using excerpts from the previously published articles.

While the revolution of 1917 did indeed shake the world, the new post-revolutionary society faced many hazards. Four years of civil war disrupted Soviet society, destroyed a good deal of the infrastructure, and brought much death and destruction. The new revolutionary society also faced the intense desire of the great powers—the United States, Great Britain, France, etc.—to crush the Bolshevik Revolution in its cradle. And yet in the face of extreme difficulties, as soon as the Soviet Union could catch its breath, it worked with deliberate speed to provide equal access by the people to housing, education, medical service, and care of the elderly and disabled. Striking, indeed sensational, was the attainment and maintenance of full employment at the same time that the West was mired in the Great Depression; typically in even the richest countries during those years unemployment ranged between 20 to 30 percent of the labor force.

Harry Magdoff made a tour of U.S. machine tool companies in preparation for developing a plan for that industry during the Second World War. Time and again owners reported that their survival in the depths of the Depression was due to the flow of orders from Russia for its five-year plan. Moreover, pulling itself up by its own bootstraps, the Soviet Union transformed a backward, industrially underdeveloped society into an advanced industrial country—one that was able to equip an army and air force that not only stood up to the German invasion during the Second World War but also played a major role in the final defeat of the German army. Still, the ultimate socialist goal was in no small measure diverted at an early date, largely because of the development of a privileged bureaucratic elite and a distorted nationalism.

Bureaucracy and Nationalism

The post-revolutionary society in Russia moved far away from the proclaimed socialist ideal advocated by Marx and Engels. The latter didn’t design blueprints for a new society nor did they predict in detail the trials and tribulations of the struggle for socialism—including the possibility of alternating failure and victory, of battles won and lost, until the transfer of power from the upper to the lower classes was firmly established. But they never faltered in their faith in a final victory, learning from the currents of their time and reaffirming the principles of people’s republics. Thus, the Paris Commune was not only celebrated but also studied, as in Marx’s The Civil War in France. Engels’s introduction to the essay pointed to the distinctly socialist policies of the Commune. Of critical significance, in his opinion, was the Commune’s attempt to safeguard against the development of a leadership that could become new masters:

From the very outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not go on managing with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials….

Against [the] transformation of the state and organs of the state from servants of society into masters of society—an inevitable transformation in all previous states—the Commune made use of two infallible means. In the first place it filled all posts—administrative, judicial, and educational—by election on the basis of universal suffrage of all concerned, subject to the right of recall at any time by the same electors. And, in the second place, all officials high or low, were paid the wages received by other workers….In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set up, even apart from the binding mandates to delegates to representative bodies which were added besides.

The Soviet Revolution, in contrast, faced special conditions that led to the growth of a bureaucracy that came to dominate Soviet society. Trotsky’s observation at the close of the Civil War is worth noting: “The demobilization of the Red Army of 5 million played no small role in the formation of the bureaucracy. The victorious commanders assumed leading posts in the local Soviets, in the economy, in education, and they persistently introduced everywhere that regime which had ensured success in the civil war. Thus on all sides the masses were pushed away gradually from active participation in the leadership of the country” (The Revolution Betrayed).

The bureaucracy grew like a cancer during the rough and tough times of recovering from the First World War and the ensuing civil war. Control over the economy and society before long was concentrated in a state ruled by a small minority who had a strong hold on state power. Alongside, an elite sector of the population—party leaders, heads of industry, government officials, military officers, intellectuals, and entertainers—rose to become a privileged stratum. Stratification of the population and hierarchy set in for the duration, influencing the patterns of accumulation and contributing to reproducing the new social formation. Stratification brought benefits to the privileged top: not only in income, but more strikingly in the differences in the quality of medical care, education, living quarters (country homes as well as large urban flats), vacation resorts, hunting lodges, automobiles, and supplies of food not available in markets. Naturally, the more consumption that went to the elite, the less was available for the rest of the population. And the privileges and power of members of the upper strata were replicated in their offspring. However, as distinct from capitalism, there was no inherited ownership of the means of production.

The hierarchical command system ruled with a heavy hand over most aspects of civilian life as well as over the economy as a whole. The outstanding features of its extensive bureaucracy were rigidity and an ever-present sense of insecurity in the privileged sectors—the need to protect one’s own interest and avoid expulsion from one’s privileged position, let alone staying out of jail. As a rule, hierarchy penetrated institutes, industrial enterprises, and industrial syndicates. Thus, the soviet system produced its own contradictions: a bureaucratic structure which operated far removed from the masses and was so rigid and entrenched that it could sabotage economic and political reforms designed to improve the efficiency of production and distribution. In keeping with these developments, wide differences in living conditions among sections of the population, republics, and regions were created. Within each republic, upper and middle social strata diligently strove for higher status and a way of life similar to that of the upper and middle classes of the West.

A second major departure from socialist principles took place on the nationalist question. In the nineteenth century the Tsars had energetically acquired extensive areas, consisting of nations with diverse ethnic populations. The Tsars and nobility had built an empire. Communist Party leaders differed on how to handle this after the Tsar was overthrown. What should be done as socialists? Lenin was firm in his stance: create a federation of states in which each one would have the right to secede. Moreover, the constitution should provide a rotation of presidents of the Soviet Union from one nationality to another. Stalin ridiculed Lenin’s policy suggestions as being romantic. The upshot was a federation in which Russia became the center and Russification the rule.7

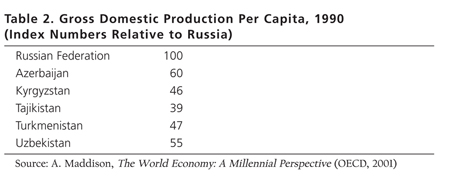

The ensuing economic development reflected the dominant status of Russia. It is true that after the revolution, the republics in the Soviet Middle East and Asian republics did advance significantly in a number of respects. For example, the living standards, education, and cultural facilities of the Soviet Middle Eastern republics were far above those of the same ethnic peoples on the other side of the border. Similarly, progress was also spread to Asian Soviet republics. Nevertheless, major differences between the center and periphery remained. An official statistical handbook of the Soviet Union reported in 1987—70 years after the revolution: “for the country as a whole 21 percent of pupils are…in schools without central heating; 30 percent without water piping, and 40 percent lacked sewage” (The USSR in Figures for 1987 [Moscow: Finansy I Statistika, 1988]). These deficiencies, we believe, indicate the scale of priorities adopted by the Russian center. Thus, in Turkestan, for example, more than 60 percent of the maternity hospitals, wards, and children’s hospitals had no running water, and about two-thirds of the hospitals had no indoor plumbing (Nikolai Shmelev and Vladimir Popov, The Turning Point [Doubleday, 1989]). The revolution brought significant benefits to the former colonial areas, but major differences remained between the core and the periphery. The overall picture is illustrated by the data in the accompanying table comparing the gross product per capita of Russia and several Asian republics after seventy years of Soviet power (table 2).

In addition to differences between Russia and the former Tsarist colonies, major differences also remained in Russia itself—in living standards and quality of life between Moscow and backward regions.

Planning and the Soviet Economy

Most of the problems that led to the crisis in the Soviet Union in the later part of the twentieth century are related to the economy and the way it was organized during the early years of the revolution. It is common to blame the Soviet Union’s difficulties on the use of central planning. There are even those who claim that it is impossible to have a planned economy in a large and complex country, and some offer “market socialism” as an alternative (see below). However, the economic failure was not of planning per se, but rather grew out of the particular characteristics of Soviet planning—a system developed under unique circumstances and which took a very different direction from that imagined by the early revolutionaries. What happened in the Soviet Union was, in essence, planning without a realistic plan. The Soviet Union did not have to embark on an ambitious program of central planning and massive industrialization when it did in the late 1920s. An important part of the leadership, led by Bukharin, advocated a slower and more gradual course. But, once a decision was made, it was inevitable that certain consequences would follow from the initial goal of an incredible rapid acceleration of economic growth under unusually strained conditions: a vast increase in the economic role of the state, extreme concentration of decision making, and harsh regimentation of the people. The first Five Year Plan set the stage for much of what was to happen in the Soviet Union—economically, socially, and politically. The twin goals of rapid industrialization and the build-up of a strong defense capability—both important given the international situation—dominated Soviet thinking beginning with the first plan in 1928. The attempts to implement an overly ambitious plan given the available human and natural resources—and not developed with broad participation of the masses—led to the routine use of threats and coercion.

As long as the economy was able to sustain a rapid growth rate, there was enough maneuvering room to keep the contradictions from reaching the boiling point and exploding. But when the growth rate slowed down and the economy finally stagnated in the 1960s–1980s the stage was set for a profound crisis—one that ultimately led to the reestablishment of a bastardized form of capitalism. But why did a coercive command economy with strict hierarchical control—only one of a number of ways to proceed in 1928, but which performed well in the 1930s and 1940s—begin to stagnate in the later years? During the early years, there were plentiful supplies of labor in the cities and more that could be brought in from the agricultural regions as well as a large endowment of natural resources. It was therefore possible to organize the building of factories with strong government control coordinating the use of both human and natural resources, leading to rapid growth in employment and in production. Appeals to nationalism and the ideals of the revolution also played a part in inspiring this development, especially when the country was faced with the threat and then the reality of war.

However, once the post-Second World War reconstruction was finished, a number of obstacles lay in the path of renewing high rates of growth using a centralized command economy that attempted to control almost all economic decisions. In this situation, procedures previously used became counterproductive. First, there was relatively small growth in the working age population (because of the huge loss of people of childbearing age in the Second World War and the general decline in the birth rate). Second, there was increasing difficulties extracting raw materials, as the easier to work deposits were depleted. In 1974, before most had recognized a social and economic crisis in the Soviet Union, Moshe Lewin wrote:

Unnoticed for some time [in official circles] were those self-defeating features in the economic mechanism that had appeared in the early 1960s. Growing means devoted to accumulation and investment ironically led to falling returns on investment and a dwindling growth rate….Research showed that that the growing cost of the operation slowed down the whole process, and that the strategies employed had become blatantly counterproductive and urgently needed revision. The unilateral devotion to priority of investment in heavy industry, which was supposed to be the main secret of success, together with the huge injections of labor force and coercive political pressure, appeared as factors in this slowdown. Yet dogmas and practices behind them were tenacious. Heavy industry still continued to be lavishly pampered, at the expense of consumption, with relatively more products serving heavy industry rather than benefiting consumption. “Production for production’s sake” certainly expressed the position of the Soviet economy, and neither the standard of living nor national income adequately benefited from it. (Moshe Lewin, Political Undercurrents in Soviet Economic Debates [Princeton University Press, 1974])

As an economy develops, more investment is usually devoted to replace worn-out or obsolete equipment with better new machines, leading to higher labor productivity. However, the Soviet emphasis on building and equipping new plants as the way to continue growth led to neglect of the older factories. Workers were forced to continue to operate inefficient and obsolete equipment, with frequent work stoppages caused by equipment breakdowns. The shortages of raw materials also led to a much slower building of new facilities than expected.

Efficiency in the Soviet economy didn’t grow as expected because energy was dissipated in different directions—heads of syndicates were judged by how many more factories they could build and not by the efficiencies of the already existing factories. Thus, investment went preferentially into new factories, many times without having the resources to finish the job. The planners and syndicate directors did not logically determine what needed to be produced and for whom and then figure out the best way to go about it. Instead, building big factories became an ideology.

Factories were generally based on the Ford Motor Company’s former principle whereby each syndicate made all the different components necessary for what it produces—glass, ball bearings, steel, etc. In that way of organizing production a lot of potential efficiency is lost because without multiple possible suppliers, a production problem in one sector can shut down the entire syndicate for lack of a part. There were also other notorious inefficiencies in the Soviet economy. In rural areas there were insufficient silos for grain storage, resulting in much spoilage. And the lack of decent roads between country and town slowed down transportation of goods.

Clearly, the social and economic crisis that preceded Gorbachev was not an accidental phenomenon. As constituted, the Soviet economic system could produce growth as long as there were ample resources that could be mobilized. But with the exhaustion of the resources, the magic of the command economy evaporated. The failure to change from a system chosen during an early stage of Soviet development—that became a perpetual command and control economy based on continuous growth of heavy industry and that simultaneously developed a large and entrenched bureaucracy with numerous privileges and generous perks—meant that there was no way out.

After Stalin’s death, a number of solutions were discussed and attempted. But what was needed was an overhaul of the existing system—brought forth by the revolutionary activity Marx wrote about. Reforms attempted and projected were sabotaged because they threatened the jobs or status of the leaders of industry and other privileged sectors. We suspect among the top dogs there was a growing interest in privatization of the means of production as a road toward wealth and security for themselves and their offspring.

B. The Experience of China

When the Red Army, led by the Chinese Communist Party, entered Beijing in 1949, the work needed to create a road to socialism far exceeded the labors of Hercules. Great hunger raged in the land. The kind of poverty existed that Gandhi no doubt had in mind when he declared, “Poverty is the worst form of violence.” There was no health care system while diseases of all types were widespread. The masses were illiterate. Education was minimal. All these abysmal conditions combined to produce an amazing fact: average life expectancy in China at that time was thirty-five years!

The new regime turned the old society upside down as meeting human needs became the main priority. A nation-wide health system was established and campaigns were initiated that greatly reduced and sometimes even eliminated widespread diseases. Educational facilities were vastly expanded and an extensive literacy drive produced literacy far and wide. The Iron Rice Bowl was introduced—a system of guaranteed lifetime employment in state enterprises and a secure retirement pension. And in the early 1950s every peasant got a share of, to quote Bill Hinton, “that most precious and basic means of production, the land.” A striking upshot of all these efforts to improve people’s lives was that average life expectancy rose to sixty-five years by 1980!

However, the radical social achievements in the absence of meaningful democracy opened up opportunities for the growth and impact of bureaucracy. Throughout Mao Zedong’s writings of those years he railed against the new bureaucracy that not only acted as commanders over their subordinates but also obtained special privileges for themselves. Time and again Mao made clear the dangers. Here is the way Mao’s close collaborator, Zhou Enlai, described the danger:

For quite a long period, the landlord class, the bourgeoisie and other exploiting classes which have been overthrown will remain strong and powerful in our Socialist society; we must under no circumstances take them lightly. At the same time, new bourgeois elements, new bourgeois intellectuals and other new exploiters will be ceaselessly generated in society, in Party and government organs, in economic organizations and in cultural and educational departments. These new bourgeois elements and other exploiters will invariably try to find protectors and agents in the higher leading organizations. The old and new bourgeois elements and other exploiters will invariably join hands in opposing Socialism and developing capitalism. (“Report on the Work of the Government, 30 December 1964,” as cited in Maurice Meisner, Mao’s China and After [Free Press, 1986])

At heart, as Mao pointed out, even some in high Communist Party positions wanted to take the “capitalist road.” Mao’s purpose for initiating the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was to mobilize and engage millions and millions from all sectors of society—workers and peasants as well as students and intellectuals—in a struggle against the forces within the Party that favored the restoration of capitalism. Among most intellectuals in China and the United States, the Cultural Revolution has been viewed as an era of inhumane chaos. It is true that the Cultural Revolution was chaotic, with various Red Guard factions (some were even sham Red Guards, possibly organized by those under attack to confuse the masses) and many instances of exaggerated and inhumane treatment of people, including killings. On the other hand, in the rural areas this period is commonly viewed in a more positive light—an era when much infrastructure was built and attention paid to problems of the great mass of people living in the countryside.

A great change—in fact, a reversal—in the direction of China’s economic and social development, began in 1978, two years after Mao’s death, when top party officials undertook major reforms that departed from essential features of the revolution. (See William Hinton, The Great Reversal: The Privatization of China, 1978–1989 [Monthly Review Press, 1990].)

We are not able nor do we desire to diagnose the psychological or personal aims of the designers of the new direction nor have we tried above to outline all the twists and turns the Chinese Revolution took following 1949. What has become clear is that for a long time sharp differences existed within the leadership of the party about the structure of the society and the strategy of its development. On one side were those who wished to (a) confront the foreign imperialists (who in effect controlled and invested in areas on the East coast), (b) escape from the old feudalist culture, (c) prioritize aid to the peasants, and (d) overcome Han chauvinism, paying extra attention to the national minorities. On the other side were those who sought to make China a great power by giving first priority to industrialization and the speed of its development.

We write not as specialists on China. The above description is the way we read recent history, notably the avowed aim to rely on what the “reform” leaders term “socialism with a Chinese face” (also sometimes referring to “socialist market economy”). More and more information is becoming available about important features of the reversal. A major aim of the revolution had been to create an egalitarian society. And indeed that was the direction in the first thirty years. “Socialism with a Chinese face,” in which Deng Xiaoping proclaimed that “to get rich is glorious,” rapidly moved toward the “capitalist road” that Mao feared—with the most negative environmental and social attributes of capitalism, discussed above (section 2), now brought into full force.

China’s new course has indeed resulted in an extremely rapid increase of production and total national income. Although many are awed at this high rate of economic growth, it should be kept in mind that much of the growth was made possible by the infrastructure developed during the revolutionary pre-“reform” period. It was also made possible by a huge increase in exports (from $0.6 trillion in 1990 to $4.3 trillion in 2003), financed by mainly foreign capital making super profits based on extremely low-wage, disciplined Chinese labor. Under a strategy of highly capital intensive investing in labor-saving machines, “over 90 percent of the average annual 11.2 percent value added growth in industry in 1993–2004 was in the form of labor productivity growth rather than employment growth” (World Bank, China Quarterly Update, April 2005). With the high rates of economic growth concentrated in automated industries producing primarily for export and workers unable to organize meaningful militant unions, the wealth created has not trickled down very far. The result is a very rich upper strata and a comfortable middle class, replacing the earlier egalitarian order, and as for the rest: poverty, insecurity, unemployment, and a decline in education and medical care. The effect of the turnaround on the large mass of poor is finally being acknowledged in official circles. The political department of China’s Ministry of Finance issued a report on the subject. People’s Daily Online (June 19, 2003) ran an article containing the substance of the document. The article started off by stating that the report had revealed among other things: (1) “A ceaseless widening of the gap in income distribution and the aggravated division of the rich and the poor is occurring” and (2) “Amassed wealth is becoming more concentrated, with the difference of family fortunes becoming bigger and bigger.”

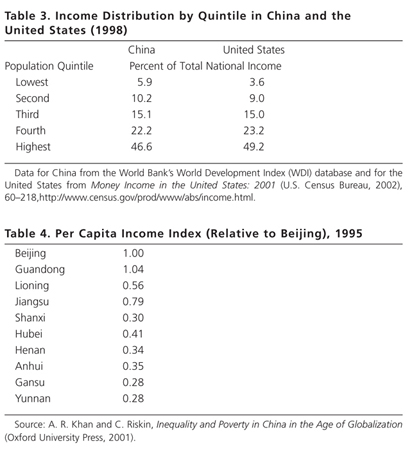

The rapid development of inequality has now reached the point where China’s income distribution is almost the same as that of the United States (see table 3). In addition, the inequality of income occurs from region to region (table 4), with much of the growth concentrated in coastal areas.

One of the most important lessons to be learned from China’s reversal in direction, in our view, is that so-called market socialism has an inner logic. One step leads to another down a slippery slope toward capitalism. The defenders of the reversal point to the fact that the state still owns the remaining nationalized companies. However, that too is changing. In February the State Council reported that it was now permissible for “private companies legally [to] engage in oil exploration, set up banks of a certain scale, provide telecommunications services and operate airlines. Other sectors now open include utilities, health and education, and defense” (Wall Street Journal, Feb 28, 2005). And as pointed out by a headline in the Financial Times (May 1, 2005)—“China gives go-ahead to sell state holdings.” This process has already begun. It is manifested in a sale of stock in four state-controlled companies, starting with “the Shanghai Zi Jiang Enterprise Group, a packaging maker; Sany Heavy Industry, which makes machinery; Tsinghua Tongfang, a computer company; and the Hebei Jinniu Energy Resources Company, a coal company” (International Herald Tribune, May 9, 2005).

4. ‘Market Socialism’ versus Planning