Also in this issue

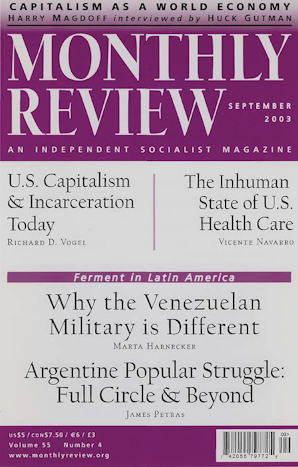

Article by Richard D. Vogel

- The Fire Inside

- Transient Servitude: The U.S. Guest Worker Program for Exploiting Mexican and Central American Workers

- Harder Times: Undocumented Workers and the U.S. Informal Economy

- The NAFTA Corridors: Offshoring U.S. Transportation Jobs to Mexico

- Capital Punishment Update

- Silencing the Cells: Mass Incarceration and Legal repression in U.S. Prisons