Also in this issue

- James Hansen and the Climate-Change Exit Strategy

- The Migration and Labor Question Today: Imperialism, Unequal Development, and Forced Migration

- The First Weapon of Mass Destruction

- What Does Ecological Marxism Mean For China? Questions and Challenges for John Bellamy Foster

- Toward a Global Dialogue on Ecology and Marxism: A Brief Response to Chinese Scholars

Books by Alice Walker

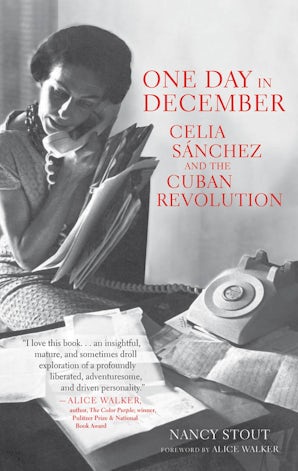

One Day in December

by Nancy Stout

Foreword by Alice Walker