[Review published in Socialism and Democracy, vol. 27, no. 1 (March 2013)]

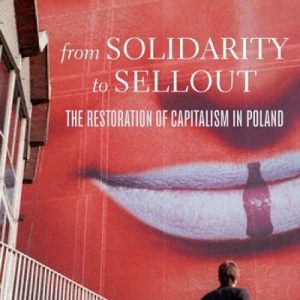

Tadeusz Kowalik, From Solidarity to Sellout: The Restoration of Capitalism in Poland (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012)

Ludmila Melchior-Yahil

Stony Brook, New York

Professor Tadeusz Kowalik (1926-2012) was one of the few Polish economists who consistently criticized Poland’s transformation to a market economy for failing to satisfy the material and social needs of the majority of the population. From Solidarity to Sellout presents a compilation of Kowalik’s writings on the subject over the past twenty years. As one of the leading intellectuals who supported the Polish working-class movement since the ‘70s (especially during the Solidarity period), the author has an extensive knowledge of both the economic debate and the political meandering that took place in Poland after 1989. In his book he focuses in particular on the so-called Balcerowicz Plan and the ensuing transformation of ownership. (Leszek Balcerowicz, a leading Polish economist and Minister of Finance in the government of Tadeusz Mazowiecki (1989-90), is widely considered the architect of the Polish “jump into the market” strategy.)

The author’s professional condemnation of the social injustice resulting from “shock therapy” is closely related to his personal grief over lost opportunities and the part Polish intellectuals played in bringing negative changes. In his opinion, Solidarity, as “the largest worker movement that twentieth-century Europe experienced” (13), provided Poland with an unprecedented and unrealized chance to create a modern and just society. This assessment of Solidarity determines the scope of the author’s analysis, although his focus is more on micro-political events and debates than on macro social and economic processes or global strategies.

Post-1989 Poland appears as a land open to any economic experiments, except, of course, the communist model. The key positions of power were taken by humanitarian intellectuals, later in alliance with the new technocratic-managerial elites (290). Those intellectuals had good intentions, but lacked knowledge and experience in political and business matters. Their good intentions are compared to those of Margaret Thatcher, who “saw no possibility of guiding Great Britain onto the path of more rapid growth without breaking the resistance of the miners” (278). Even if we assume that rapid growth of the national economy was indeed the main goal of both Thatcher and Poland’s first post-1989 government, she did not come to power as a former coal miner union organizer. The tragedy of many Solidarity intellectuals (Jacek Kuron being probably the best example here) stems from the fact that for a variety of reasons, consciously or not, they participated in the destruction of a social movement that they helped to create and which brought them to power. They watched as the workers who had fought in coal mines and shipyards to bring down the nomenklatura of “real socialism,” fell from the position of the most privileged part of the Polish working class to that of the unemployed and destitute.

In the ongoing debate over what determined the specific character of transformation in various post-communist countries, it is difficult to ignore that Poland, with its strategic position and population of 38 million, was faced with very different options than Slovenia, or even Hungary. That’s why certain comments of the author about his former colleagues – “Mazowiecki did not anticipate”; “Kuron was enchanted with Sachs” and even “Sachs didn’t realize” or Kwasniewski “was no wiser earlier” – can be ascribed only to his faith in human nature. Certainly, many of the new leaders were not economists and therefore did not fully understand the pitfalls of the “shock therapy” they set in motion. Others considered its tragic social consequences a necessary evil and the inevitable price for economic transformation. It is also true that every sweeping systemic change brings unpredictable and often chaotic phenomena that are difficult to control. However, more than twenty years later it is easy to see that the Polish transformation, while disastrous for some social groups, was quite profitable for other players (both local and foreign).

Some of the Polish reviewers of Kowalik’s work (like Ryszard Bugaj) objected to the way he overestimates the real influence of the central government and underestimates the spontaneous mechanisms occurring during the transformation process. However, a case can be made that Kowalik underestimates as well the deeper socio-economic and political changes that were taking place in the Soviet bloc prior to its disintegration, as well as the fact that they did not occur in a geopolitical vacuum. His approach limits his analysis of the “enfranchisement of the nomenklatura” and of “corruption-clientelism” in Poland. Even talking about the Soviet Union, Kowalik states that it was Gorbachev’s glasnost that “aroused the hostility of the corrupt apparatchiks who were scared to death of the criticism and in consequence launched an uncontrolled process that ultimately led to the disintegration of the USSR and the breakdown of the system” (29). In reference to Poland, he talks about “wild” or “uncontrolled” privatization, while at the same time delineating a quite “tame” and “controlled” sell-out of state assets, with the best enterprises bought by foreign capital (243).

One can only wish that the author had had more time to write on this subject, as well as to elaborate on some of his more alarming statements. He writes about falling wages, growing unemployment and the breakdown of social services: “Poland has created one of the most unjust social and economic systems of the second half of the XX century” (290). As true as this statement may be if one bases the analysis on selected official statistical data, any astute observer of Poland during the most austere years before and after 1989 can attest that this evaluation is only a small part of the story about a society that through centuries of mistrusting successive governments (be they native or foreign) developed a very sophisticated alternative system: the unofficial economy, mutual help and self-reliance….

Read the entire review in Socialism & Democracy

Comments are closed.