While communications about the military successes of the People’s War in Nepal have been regularly disseminated, little information has been made available at the international level about the achievements of people’s power in the country. This article aims to rectify this situation somewhat by highlighting the emergence of people’s power side-by-side with the progressive dissolution of the old monarchical state (ruling since 1769), with particular reference to achievements made in the Central Command area, which includes the main base area, Rolpa.

Introduction

Since the founding of the Communist Party of Nepal in 1949, the destruction of the old monarchical state and construction of the New Democratic state have been coveted dreams of most of the people of Nepal, where mass-based support for communism has been generally high. From the initiation of the People’s War in 1996 up to the present period, around 80 percent of Nepal has come under the control of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), hereafter referred to as the CPN(M), while the old state’s presence is now limited to the capital, district headquarters, and highways. The hallmark of the People’s War in Nepal is the rapidity with which the old state has crumbled, forcing imperialist countries to designate the old state as a “failed state.” Today the king’s last saving force, the Royal Nepal Army, is limited to its barracks and occasional forays of destroy and retreat into rural areas. This has been possible due to multiple factors, the first being the ability of the new state in the form of people’s committees to be strategically firm and tactically flexible in handling contradictions between the international, national, and local. Second, it has been able to place political initiatives ahead of military offensives. Third, it is undertaking construction work side by side with destruction of the old state. Fourth, it has addressed oppressed nationality, gender, regional, and caste issues long neglected by the old state. Fifth, it is a home-grown movement creatively using Marxism-Leninism-Maoism to analyze the concrete conditions of Nepal and then translate this analysis as the basis for concrete action. Finally, through its total war strategy, it has been able to undermine the old state centrally using political offensives and locally through military strikes by destroying old rural bastions and filling the vacuum with people’s committees. The holistic approach of People’s War has made it difficult for imperialist countries to term the Maoist movement in Nepal as “terrorist” war.1

It should be noted that all these have been made possible through sacrifice of thousands of conscious martyrs, including many office-bearers of the new state.

Theoretical Premises

The question of state power is central to the revolution. In a country where Protracted People’s War is being waged, the question of developing base areas has a strategic place in terms of supplying manpower, logistics for war, and psychological and ideological well being. With the war entering a strategic offensive stage, the question of consolidating base areas becomes all the more important.

From the very beginning even before the people’s war started, the CPN(M) was clear about the nature of the new state. It envisioned a New Democratic state, which would exercise people’s dictatorship over feudal and imperialist forces, including expansionist states, while granting democracy to oppressed classes, castes, nationalities, regions, and women. However it was also made clear that this revolution may need to go through various sub-stages, zigzags taking into consideration Nepal’s specific geo-political condition. Thus in Nepal’s case, the Party had already envisaged that the New Democratic state in Nepal shall take the form of a class, national, and regional United Front under the leadership of the proletariat. This is because a high percentage of the population in Nepal falls into the oppressed class, with many different nationalities and regional divisions.2

Taking note of the lessons to be learnt from counter-revolutions in socialist states, the CPN(M) has passed a resolution on “Development of Democracy in the 21st Century” in 2003. This resolution mentioned that the question of continuous democratization of the state power leading to the withering away of the state is a thousand times more difficult and complex than capturing state power. Thus the key question is how to combine the dictatorship of proletariat with elements of continuous revolution in running the state. This can only be done by putting politics in command and subjecting the state to the control, supervision, and intervention of the masses so that the people’s front goes on expanding while reactionaries’ base continues to shrink.

Development of People’s Power

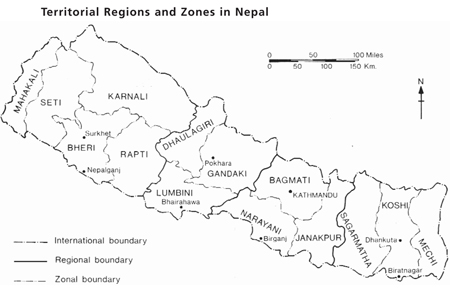

The concept of a New Democratic State took concrete shape only after the initiation of the People’s War. The rapidity with which local people’s power sprouted in different parts of Nepal can be judged by the way that the People’s War by its second year had created a power vacuum in various rural areas, mainly in western Nepal. Different levels of embryonic people’s power started filling the power vacuum under the three regional commands in the form of United People’s Committees. Initially these areas were defined militarily in the form of main, secondary, and propaganda areas. Within two and a half years there was already discussion of building a base area in the main area of the western region, due to the strong mass base, strong position of the Party, favorable terrain, elimination of social class enemies by the guerrilla squads, and to a certain extent the defeat of local military strength of the reactionary state in that region. Thus a call was given for conversion of main zone to base area and secondary zone to guerilla zone. By the fifth year of the People’s War, the Party had advanced the slogan “Consolidate and Expand Base Areas. March Towards the Direction of Forming New Democratic Central Government.” The same year the First National Convention of the Revolutionary United Front consisting of the representatives of the CPN(M), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), various class and mass organizations, local People’s Committees, and prominent personalities was held (September 2001), which founded the United Revolutionary People’s Council, Nepal. With this formation, a dialectical relation emerged with the central United Front, in which the United Revolutionary People’s Council intervening politically calling national bandh and chakka jam (strikes and general stoppages) and calling for dialogue, constitutional change, etc. from the old state at the central level, together with exercising People’s Power through various people’s committees at the local level. This amounted to an all-out attack on the old state. By the seventh year of the People’s War (2003), nine national and territorial autonomous regions had been formed throughout the country—from west to east: Seti-Mahakali autonomous region, Bheri-Karnali autonomous region, Tharuwan autonomous region, Magarat autonomous region, Tamuwan autonomous region, Tamang autonomous region, Madhesh autonomous region, Newar autonomous region, and Kirat autonomous region. Out of these the first two are territorial autonomous regions and the rest are national autonomous regions (see “Territorial Regions and Zones in Nepal” map below).

Territorial Regions and Zones in Nepal

Under these regions People’s Committees are functioning right from the district level to village to ward levels. While many of these committees are nominated, some are elected. The present trend is to continue increasing the elected committees. In order to consolidate, centralize, and unify the work of People’s Power, some ward-level people’s committees have been brought together to form Model Villages, where generally almost all members of the households are organized under the Party, mass front, or militia, thus making them a revolutionary iron fort for People’s War. In these model villages women and Dalits have been given special rights of representation in people’s committees, women are granted equal right to parental property, and ostracization of Dalits is banned. The schools are run on the new syllabus prepared by the education department of the CPN(M) and students are being taught in their mother tongue. Today a number of communes in various stages of development are functioning, together with several agriculture-based cooperatives functioning in the base areas throughout the country.

It is important to note that one of the reasons why people’s power was able to spread and consolidate so fast throughout Nepal is because of the background prepared by United People’s Front (UPF), a legal front for the then underground CPN(M) before the People’s War started. The UPF was able to expose the then monarchical parliamentary system and to propagate for the New Democratic revolution (while occupying a position both in parliament and outside it), spreading an organizational network throughout the country which facilitated in converting the local organs of UPF into people’s committees after the People’s War started.3

The Present State of People’s Power in the Base Areas

Out of the three commands—Western, Middle, and Eastern—covering the whole country, the Middle Command has been chosen in this article as a focal command because the People’s War has had the strongest impact in this region. Within this command there are two sub-regional commands: Gandak and Special Sub-region. Within the Special Sub-region all districts comprising Rolpa, Rukum, and Salyan under the Magarat autonomous region are being organized as the main base areas. Among these, the main base area in Rolpa is relatively older, more stable, and consolidated than the rest. Within Gandak sub-region, secondary base areas under the Tamuwan autonomous region in the Northern Gandak and Magarat autonomous region in the southern Gandak are being organized. These base areas, however, are relatively unstable. In those areas which fall between the main base areas and secondary base areas, the vacuum created due to destruction of the old state is being filled by embryonic people’s committees. Similar situations with some variations are operating in the rest of commands throughout the country. The capital Kathmandu and district headquarters are still under the control of the old state, although the surrounding new states are able to impede their functions through national, regional, and local bandhs and blockades of goods, which often paralyze life in the capital.

With the promulgation of the Common Minimum Policy and Programme of United Revolutionary People’s Council and the passing of the People’s Power Directives as guidelines for running the new state, the base areas in particular have started taking organized, systematic shape (see “The Rapti Zone” map below).

Different Elements of People’s Power

One of the first indications of the failure of the old state and emergence of the new state is in the judiciary. The mobile, locally-based people’s court soon replaced the old formal court system. So popular was the people’s court system that even those who did not readily accept the authority of the new state accepted the service rendered by the new people’s court. Today the Public Code of People’s Republic of Nepal 2003 is being followed to regularize and systemize the functioning of the legal system throughout the country. By 2005, within the Special Region, one male and one female at the district committee level from each of the eleven districts had been given training, enabling them to function in the mobile people’s court. Similarly, an open-jail system is facilitating transformation of convicts into useful citizens. However there is a dearth of red and expert manpower. Although the Party and People’s Committees are now relatively free from getting involved in the day-to-day operation of the judiciary system, there are still tendencies to give justice straight from the Party or People’s Committees without forming separate judicial commissions. As the base areas expand and consolidate, the organizational network of the judiciary system needs to be further developed. The effective and efficient functioning of the judicial system helps in winning the confidence of the masses in the new state and hence in consolidating it. This also helps in transforming people, which is an important part of Protracted People’s War. In addition, in light of the appeal made by the CPN(M) to the United Nations and other international forums for the representation of the people’s power (while opposing the so-called representation of the military-fascist old state), the scientific functioning of the judiciary by the local new states will give further legitimization to its claim.

The people’s committees in the form of nominated bodies came into being once a power vacuum was created by the dispersal of police posts and destruction of the old state machinery. It was only in more stable periods that the people’s committees started getting elected. Today at the central level there exists the United Revolutionary People’s Council, mentioned above; at the regional level various national or territorial autonomous regions exist; and under these autonomous local districts, villages or urban wards exist. In all these levels people’s representative bodies and united people’s councils are functioning. Except for the district headquarters and along the highways, the country is under the new state’s control. In base areas the people’s committees have taken a relatively more consolidated, unified, and centralized form of rule, while in areas of expansion of base area people’s committees are not yet consolidated, with occasional interference from the old state, thus sometimes giving the impression that dual states exist. The understanding of people’s committees as being separate from the Party committees must be constantly hammered into the cadres and masses so that a more efficient and locally accountable functioning of new state power can be expected and the people’s committees have more authority to act independently. Therefore wherever possible regular elections to people’s committees with full recall must be regularly conducted, so that they are under control, supervision, and intervention of the masses.

The public administration as a separate body has not taken shape as yet. The officials working in people’s committees have been carrying out the administrative work themselves. As the struggle has progressed, separate staff, official assistants, and special committees of administration have started coming up. Many times ad-hoc commissions or committees are formed to ward off administrative bottlenecks. With the growing war expenditures a regular record of expenditures is being maintained. The most visible presence of administrative work is the postal courier system, in the form of maintenance of mobile posts at different points of communication. In the absence of a separate administrative body, officials of the people’s committees are given basic administrative training. However, within base areas, there is a need to develop a separate administrative body, which could relieve officials of the people’s committees to concentrate on mass work.

People’s Security

One of the main functions of the People’s Security in the form of militias is to provide security to the base areas and people’s committees at various stages, in short to safeguard the achievements of People’s War at people’s level. There are part-time and full-time militias who are in essence future PLA recruits. Thus the function of people’s security is also to expand the local military recruiting base for the PLA. In fact, all regional and national autonomous regions have been given the right to form their own militia in their respective areas. In big raids they participate as a supporting force for the PLA force. They not only give protection to any central or local program held in their areas but also provide logistical support to them. They give protection to injured PLA members recovering in base areas after each major military strike. They also give basic defensive armed training to the local people. In addition to providing security, they also work as production brigades in public construction work. In their free time they work as organizers too.

Because of the basic nature of military training given to militias, they are unable to give complete protection to the area of their operation when the reactionary force launches offensive attack. However, in isolated attacks launched by the enemy they are able to do a good job of defending people in coordination with the local masses.

Economic Structure and Physical Infrastructure Development

The socio-political achievements of the People’s War, including people’s power, can only be sustained by building a new economic base. In a country like Nepal where the state machinery, production, markets, and community institutions have been subordinated to, distorted, and shaped by the self-development of the global capitalist system over the course of the last two and a half centuries, a process Marx encompassed using the Hegelian term “subsumption” and Mao referred to in terms of “semi-colonial” and “semi-feudal,” the aim of the New Democratic revolution is to develop a national capitalist economic system, which is socialist in orientation, under the leadership of a Communist Party. The new state has rightly given emphasis to the agriculture sector so that on that basis industry can re-develop. It is important to note that cottage industry was thriving until the 1920s and was being further dismantled by World Bank dictates in the 1990s.

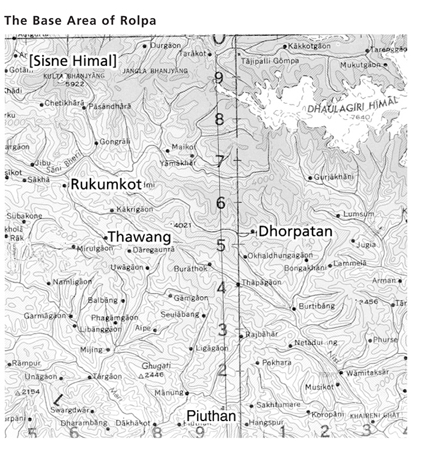

In hilly areas due to small land holdings, the emphasis has been to form a cooperative farming system, while in the Terai region the emphasis has been to distribute large chunks of land confiscated from feudal lords to oppressed masses. Many fertile lands left behind by the fleeing reactionary elements and money-lenders and the public lands previously grabbed by reactionary old-state officers have been converted into model farm land on which advanced seeds are produced and sold and new varieties of vegetables and grain have been produced as a demonstration exercise for changing the crop pattern and food habits of the people. By coordinating with the physical infrastructure development, many small-scale irrigation, hydro-electricity, water mills, and road networks have been constructed to boost farm production.4 Forest nurseries, water conservation pools, check dams together with a forest defense force have halted the deforestation process, which was rampant earlier, and now have helped in reforestation. A most remarkable example of community-based check on deforestation is the Jaljala forest which was endangering Thawang Village, the main base area in Rolpa (see “The Base Area of Rolpa” map below), through frequent flooding of the river that flows through it. There are three communes operating in various stages within Rolpa and Rukum, which is acting as model for those involved in cooperative farming to emulate. Agricultural work has been centralized in main base areas, agro-vets have provided 1–2 months basic training to the villagers and Party workers. However, there is the problem of protecting these supervised model farmlands from the reactionary army in their military operations. Many houses in Zelwang commune were set on fire by one of such military search operations. In main base areas the food, cotton, shawl, garment, soap, candle, paper making, and tannery industries all are functioning. They are mainly catering to the needs of the Party, PLA, and people’s committees. However, there is the problem of acquiring raw materials that are mostly imported from India. Also, there is still the problem of producing high quality products economically.

Regarding finance, commerce, and revenue in base areas, there are many consumer-based cooperative shops, including restaurants run by various mass fronts and people’s committees. There have been efforts to regularize private, industrial, and commercial undertakings by bringing them within the taxation regime of the new state. In regards to banking operations, a rudimentary form of mobile banking is operating by pooling shares from Rolpa, Rukum, and Salyan. At present in Rolpa alone, 1 million rupees from Thawang, 400 thousand from Bhawang and 100–150 thousand in Kureli have been amassed to operate as a bank with a 13 percent interest rate. Due to the security problem, safeguarding, and networking a banking system is difficult. Also there is lack of experience in running a people-based banking system in professional ways. Hence these banks are in an elementary phase of service.

Following the mobile people’s courts, the physical infrastructure work is most sought after. Popular works carried out by various mass fronts, PLA, and people’s committees include construction of pedestrian tracks, horse trails, irrigation systems, mill works, new school buildings, child-care centers, and other public buildings. They also include paving village roads and making green roads, providing piped drinking water, digging ponds, storing rain water, redesigning and remaking burnt down houses, making rest places and martyr gates. In short all these activities are proof of how the new state is able to unleash the talent and energy of the population. Of late, the construction of a 91 kilometer motor road from Dahavan to Chunvang and Thawang in Rolpa District by the people is worth noting. It has enhanced the image of the Maoist Party as a responsible, mature Party good not only at destroying the old state but also at constructing the new state.

Provision of People’s Health, Education, and Culture

What started as a field medical team for treating people’s army members increasingly expanded to serve civilians. Today the medical capacity of the People’s War medical team continues to expand with the growing formation of the army into higher-level military actions. Today, except for compound fractures and head and stomach injuries, most treatments are handled by People’s Army medical teams. A directive on co-operative medical management and public health has been published, enabling cooperatively run medical centers to provide medical service. New health workers of different levels are being produced through the provision of medical training (according to their educational background) conducted by experienced paramedical practitioners who have joined the movement. With practice, such new recruits are able to develop their skill much faster. Mobile medical teams are tied closely with communities and are a life-line for the injured war victims, including injured PLA members, and thus are able to provide much more effective services than the mainstream medical establishment, which has been largely ambivalent to the countryside outside of urban centers.

However, medical teams lack skilled manpower, especially full-fledged doctors specializing in surgery and other fields. The old health posts run by the old state have been regulated by the new state by asking them to follow a new code of conduct making them accountable to the people. Also, the old-state-run health posts donate certain percentages of their medicine to the medical teams of the new state.

In the field of education, the People’s War has directly intervened in existing schools with the introduction of a new syllabus and teaching in mother tongues. In some places, particularly in model villages, new schools are being constructed and run by the new state. The curriculum for the classes 1–3 and a training manual have already been prepared, as well as a draft curriculum for the social sciences for classes 4–10. Similarly a New People’s Education: Curriculum Introductory Teacher’s Training Manual 2004 has been prepared, and already thirty-one teachers teaching in schools run by the new state in Rolpa have received training. Privately run schools are totally banned in all the main base areas.

In areas of expansion of base area, in contrast, there is a policy of partial intervention in existing schools by asking teachers not to teach any materials that strengthen the old regime. The national anthem in praise of monarchy is banned, replaced by an international song or another song sung in place of old national anthem. Privately run schools are discouraged. In urban centers and district headquarters struggles are under way to reduce and provide facilities as promised while charging fees in privately run schools.5 However, there is a problem obtaining recognition for the new syllabus after the tenth class. Also, there is a problem in acquiring skilled teachers.

Since transformation of people is one of the important aspects of the Protracted People’s War, the process of destroying the old feudal culture and replacing it with a new progressive culture has been taking place. In base areas in particular, in place of the old culture, a new culture is emerging of celebrating March 8, the historic People’s War Initiation Day, and a week-long Martyr Day. Old practices such as child marriages, polygamy, and polyandry, along with incurring debts for birthday, marriage, and death ceremonies are being slowly replaced by new practices: love-based marriage at adult age (twenty for women and twenty-two for men), monogamous marriage, and simpler birthday, marriage, and death ceremonies. Similarly, liquor consumption has been brought under control, thus relieving women from harassment and poverty. Countrywide, regional, and local-level liquor bandhs (strikes) have helped in discouraging liquor consumption. In base areas limited private consumption of liquor is allowed (as liquor consumption is part of Magar culture) under the proviso that it does not disturb public tranquility. Foreign-made liquor is totally banned in base areas as is the sale of homemade liquor. In urban and district headquarters, there are calls to ban beauty contests, and letters are sent to beauty contestants calling on them to not participate or if they have participated to not accept their titles. Similarly sexual exploitation of women in massage parlors, bars, and restaurants is being discouraged by threats of sabotage. Progressive songs, dances, and dramas are being propagated in place of old idealist feudal songs, dances, and dramas. Superstitious practices are being brought under control. Everywhere community-based projects are encouraged. This is reflected particularly in community-based fodder collection, farming, and husbandry work that are part of the farm co-operative movement. With occasional cleanliness drives launched by various mass fronts including the new state, people are getting conscious of the importance of maintaining a healthy environment in and around the households.

Social Welfare

Several new organizations such as the Martyr Family, People’s War Sacrifice Family, People’s Army Family and Cadre Family have been formed to address the special needs of the families of these people. They have been organized to become active participants in the new state. Several child care centers and hostels have been constructed to house children of martyr parents, full-time workers, and poor masses. Several model villages have been organized in the base areas to consolidate people’s power. In the women-exploitation-less village women have been granted equal parental property and a special right to equal representation within the new state (50 percent). Similarly Dalits have been given special right of representation in the new state (20 percent). In these model villages all the members of the family are organized in some mass-front or the other, thus they stand out as an iron fort for the People’s War. Here it is important to note the use of the republican Nepal FM radio run by the Party to disseminate new cultural and social welfare measures to communities, along with news. Directives such as asking parents to give equal property rights to their daughters, asking them to shed long cumbersome dresses for more workable dresses, long hair for shorter hair, etc. are being propagated daily. Similarly, warnings about discrimination against Dalits are being spread through FM radio. Listening to the FM radio has become a way of life for the people in rural Nepal.

Achievements, Limitations, and Possibilities

One can proudly claim that the otherwise small obscure archaic monarchical state of Nepal, which hardly existed in the political map of the world, has today become a focus of attention not only in this region but across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Today officials of the United Nations frequently visit Nepal. All this could be achieved not only through the force of rebellion but because this rebellion has introduced a new system of state, a new value of life which bases itself on science, not religion; on responsibilities, not bondage and debt; on a universal outlook, not on obscure past values; on emancipation of women, Dalits, and oppressed nationalities and regions, not playing upon their vulnerability and oppression. And all these have been made possible by the wretched of the earth, who are otherwise languishing in other parts of the world including the so called developed world. The People’s War has indeed unleashed their creativity and energy, making them the new rulers with more responsibilities, precisely because they belong to the majority human productive force, which produces wealth not for individual accumulation but for collective gains, making humans truly social. Within Nepal, the new emerging state has shifted politics from a Kathmandu-centric focus to a rural-centric one. Today the people and interests making up the old state, including parliamentary parties, are forced to address long-neglected issues. The People’s War has undermined the old state’s feudal base, which still exists in so-called democratic countries. However the challenge today is to build a national capitalist economic base with a socialist orientation under the leadership of a proletarian Party. Lastly, it has sown hope among the working classes of the world that another world is possible and that the end of history won’t come, despite the wishful thinking of ruling-class propagandists, as long as people struggle.

There are inherent contradictions in the objective reality. Although, according to UNDP figures, this country is the second poorest in the world, it is the place where the most wretched masses are applying the most advanced scientific ideology to do away with their backward political system. Thus there is bound to be some contradiction between subjective efforts and objective realities, both within the Party and outside it. Another contradiction is that although at one end the Maoists hold most of the country, central state power remains concentrated in Kathmandu under the old state. As a result, running a new state cannot yet take comprehensive form.

Even within the new state run by CPN(M), there are many shortcomings of a political and technical nature. Often military victories are not transformed into the consolidation of base areas or existing people’s power and their expansion. This in the long run may lead to a militarist tendency, isolating the Party from the masses. There are still some problems of overzealous operation of the people’s committees, relying more on force than political conviction/persuasion to produce results, especially with regard to changing old habits and enforcing new ones. Clear demarcation between the Party’s functions and the people’s committees’ functions must be made so that people’s committees can exercise more power and function smoothly. In many areas any sort of uniform code (with local variations) is yet to be made. Considering that the People’s War is protracted, it is important to centralize and concentrate existing skills and facilities so that more effective results can be achieved rather than dissipating energy in many fields without much result. Hence more model villages must be built. Also we should note that over-involving the masses in programs and meetings of the Party while they are under-represented in running the state will also alienate them. Therefore, wherever possible, regular elections to people’s committees must be conducted. This also helps in checking bureaucratization of the new state by putting it under the control, supervision, and intervention of the masses.

Lastly, it is only by defending, applying, and developing the proletarian science of revolution that the new emerging state in Nepal can be defended and developed. From that point of view, “Development of Democracy in the 21st Century” needs to be practiced and seen in the new state. It is also the duty of other revolutionary communist forces and the International Communist Movement to defend, apply, and develop the proletarian science of revolution so that it will help unfold the red flag over Mt. Everest in Nepal, the highest peak in the world!

Notes

- But of course anything is possible for the United States. At the time of the last armistice in Nepal, which lasted from January until August 2003, the United States did its best to force a resumption of the military conflict. Just as formal talks got under way in May 2003 between the revolutionary leadership and the Palace, the United States announced that it deemed the popular revolutionary forces to be “terrorists.” The armistice ended in August 2003 when the U.S.-advised RNA murdered in cold blood twenty unarmed political activists in the town of Doramba. At the end of November 2003, then U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage announced that the CPN(M) “poses a significant risk of committing, acts of terrorism that threaten…the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

- In the 1991 census, the last before the start of People’s War in 1996, the total population of Nepal was said to be 18,492,097. Today it is estimated to exceed 25 million. In the 1991 census, the various ethnic/national identities comprised over 25 percent of the population, and the three largest Dalit (previously called “untouchable”) castes an additional 10 percent. Brahmin and Chhetri high-caste Hindus were found to be 30 percent of the population. For many of this 30 percent the advantage of high caste is slight, and political and economic relations in which they see themselves as oppressed dominate.

- In the 1991 elections the future original base area of Rolpa elected to Parliament the two candidates of the United People’s Front, Barman Budha Magar and Krishna Bahadur Mahara, both natives of the district. Krishna Bahadur Mahara is today the media spokesperson for the CPN(M).

- For readers unfamiliar with Nepal, the importance of scale cannot be overemphasized in visualizing these development efforts. Except for the one motor road mentioned later and horse and mule trails in the valley of the Gandaki River, the roads referred to are footpaths. Irrigation refers primarily to the construction and maintenance of the ditches necessary to distribute water to terraced hillsides. The hydro-electric and water mill projects involve channeling water by ditches to drive a single millstone or a small generator. Small as the scale may be, they require intense collective effort and are crucial to any gradual amelioration of life in the hills of mid-western Nepal.

- Note that the police and military of the old regime continue to control the urban centers and most district headquarters. Nonetheless the degree of support for the revolutionary cause is so strong that, even in the absence of the PLA, it can influence the organization of the schools and numerous other aspects of daily life.

Comments are closed.